The Honorable Richard Owen ’50 once penned an order for a “cursed Quaker” woman to be tied to a cart and driven through several towns where she was to be whipped “10 stripes.”

Owen, a federal judge and opera composer, wrote the sentence from his piano—not judicial—bench, as part of the libretto for his 1976 opera, “Mary Dyer.”

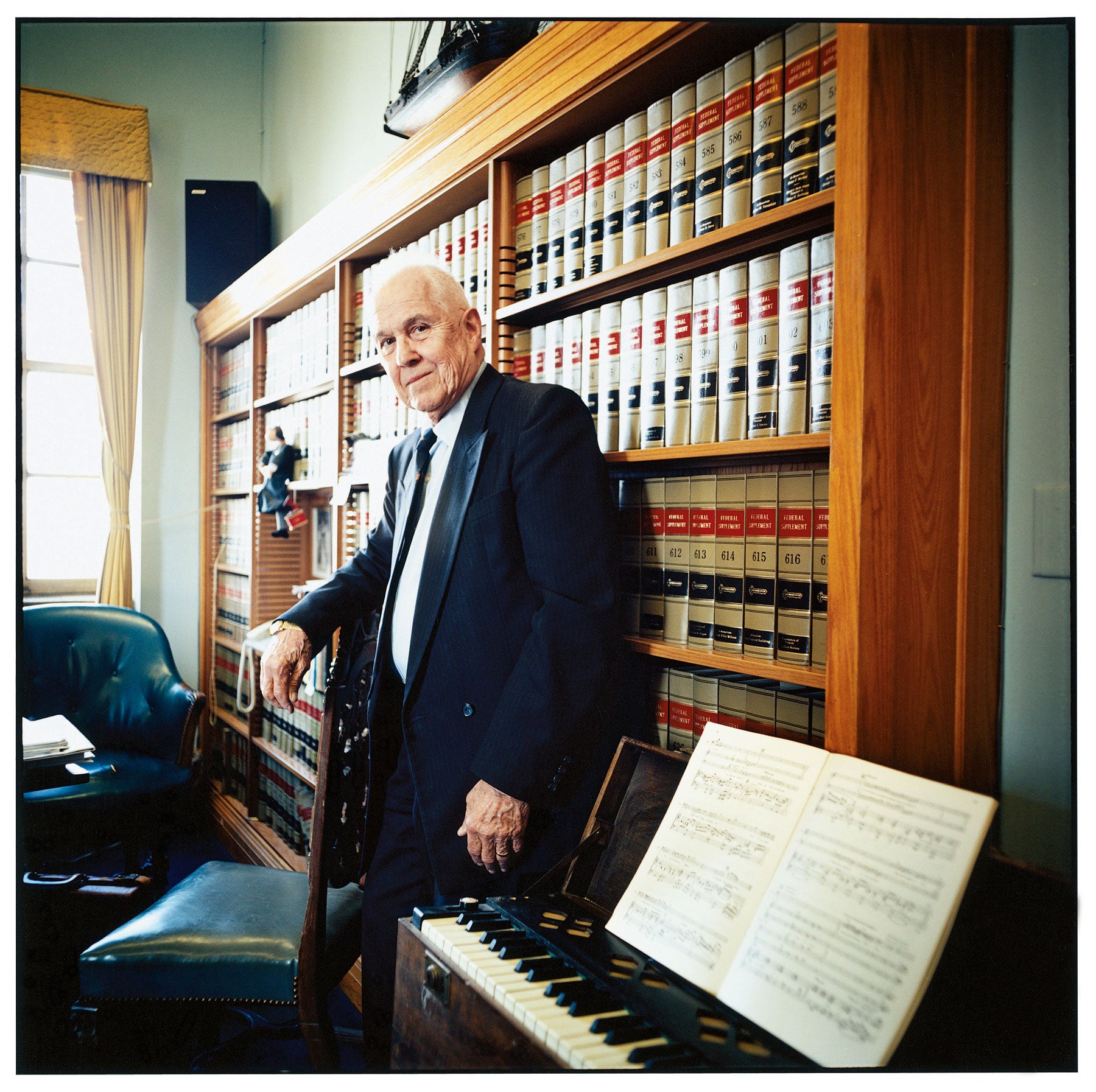

For more than 40 years, Owen has pursued both legal and musical careers. A former trial attorney, he has been a federal district judge for the Southern District of New York since 1974. He is also an opera composer and has written the words and music for eight, much-produced, operas.

Although Owen has seen plenty in his 32 years on the bench—he was the presiding judge in the 1986 Mafia Commission case, a racketeering trial that included charges of murder and extortion—he hasn’t incorporated any of that drama into his operas.

For the most part, says Owen, he writes operas about people of substance, such as Abigail Adams, or Mary Dyer, who was hanged in 1660 for standing up for her religious convictions. In “Death of a Virgin,” he wrote about Caravaggio and the woman he came to paint.

Owen grew up in New York City and recalls his father, a corporate attorney, attending the Metropolitan Opera on Monday nights. When Owen was 4, his father took him to see his first opera, “La Bohème.”

At 5, he said he knew he wanted to be a trial lawyer. He followed his father’s path from Dartmouth to Harvard Law, where, he notes, he had to study every night for months to “make damn sure” he could get through.

After securing his J.D., Owen returned to New York, where he became a trial attorney in the antitrust division of the U.S. Department of Justice. He also attended contemporary operas and soon became convinced he could do better.

He enrolled in night music classes, studied with Vittorio Giannini, who wrote the opera “The Taming of the Shrew,” and, in the early 1960s, attended composition classes at the Manhattan School of Music every Thursday he wasn’t in the courtroom.

In 1956, he took a month’s vacation to study composition at Tanglewood. Wandering the grounds, he stopped to listen to a woman rehearsing “Don Pasquale.”

“I said to myself, ‘I really don’t like that opera all that much, but that girl has one hell of a voice,’” said Owen.

He convinced the girl, Lynn Rasmussen, to sing the lead in his first opera, “Dismissed with Prejudice,” a one-act he wrote for the New York Bar Association’s spring show, and four years later they married.

Owen has written seven of his eight operas for his wife, a soprano who has sung at the Met and all over Europe. He says her voice is so lovely that when he hears her perform, he sometimes has to bite his finger not to cry. He wrote “Tom Sawyer” for one of his sons, both of whom were boy sopranos at the Met. One son is now a conductor. The other is a partner in a Manhattan law firm.

Owen says he never thinks of music when he is on the bench, although a legal argument will sometimes pop into his head while he is at the piano.

But music and the law have intersected in his courtroom. In the ’70s, Owen presided over a plagiarism bench trial, in which former Beatle George Harrison was accused of copying the melody for “My Sweet Lord” from the Chiffons’ 1963 hit “He’s So Fine.” Owen believed Harrison wasn’t being asked the right questions, so the judge pulled his chair to the witness rail, and for an hour, while Harrison played guitar, both men sang themes from the two songs. In the end, Owen found Harrison liable for subconscious plagiarism.

Now in his 80s, he is still presiding over cases and is currently working on a new opera about another condemned woman, Mary Magdalene. Although he was eligible for senior status more than a decade ago, Owen said it never occurred to him to take it. He loves the daily excitement of the courtroom, and for now, he plans to just keep humming along.