Eight days away

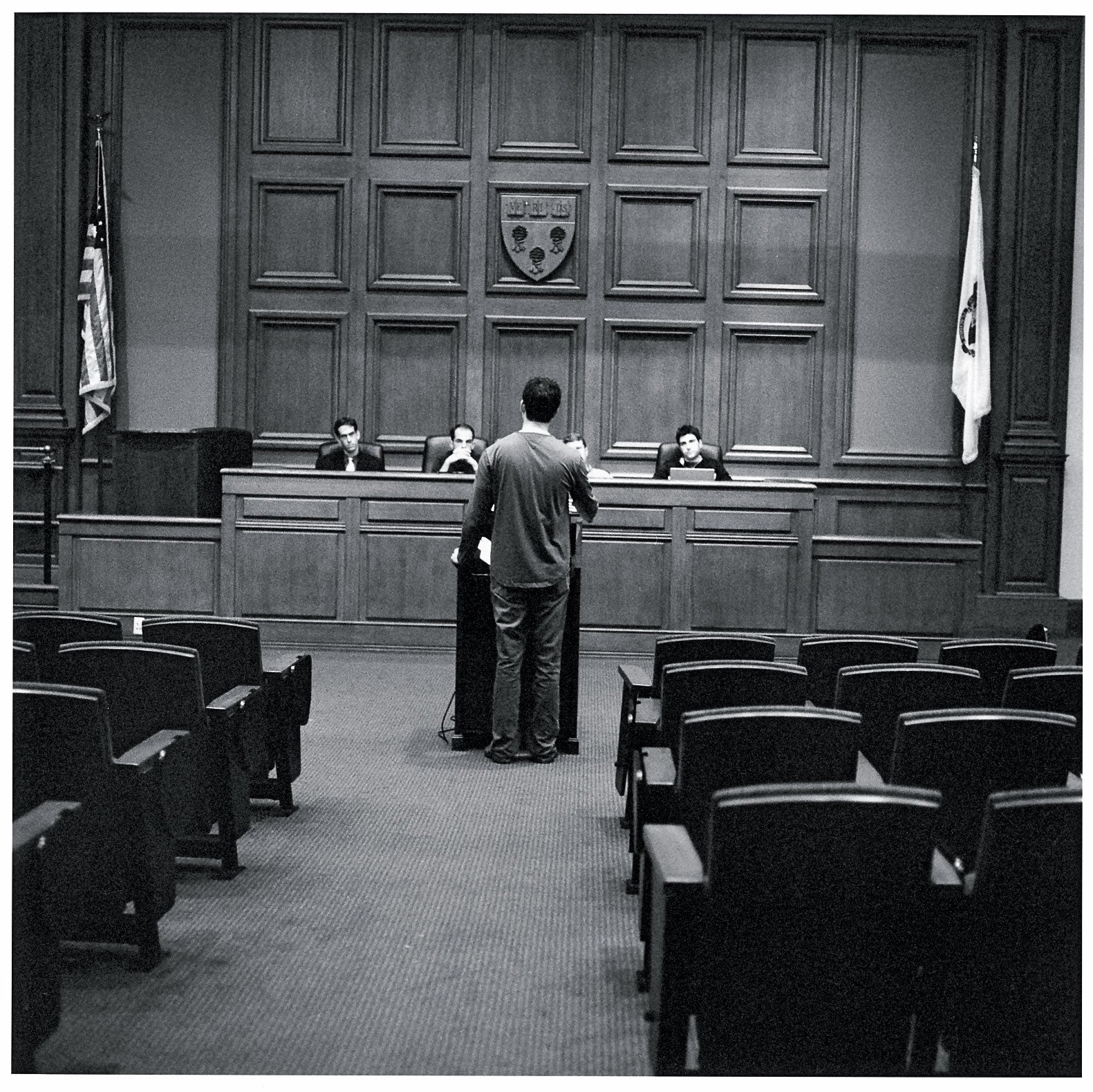

Joshua Hurwit ’06 stands at a lectern, facing four classmates. They stare down at him from rolling chairs on the elevated bench of stately Ames Courtroom. In eight days, on Nov. 17, 2005, Hurwit will stand here again, but instead of his friends, he’ll face U.S. Supreme Court Justice David Souter ’66 and Judges Emilio Garza and Ilana Rovner of the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals–the judges who will decide the winners of the 2005 Ames Moot Court Finals.

Hurwit and his five teammates have spent nearly a thousand hours researching and writing about the hypothetical case McNeil v. Lu, involving the constitutionality of a juvenile curfew law (see sidebar). They held their first meeting before classes even started in September; they submitted over 50 pages of briefs; and they’ve left 30 other teams in their wake to make it to the finals. All this work will culminate in oral arguments on a Thursday night–eight days away–when Hurwit, Bryce Callahan ’06 (the team’s other oralist) and the two oralists for the respondent team will stand before the panel of judges, a packed Ames Courtroom and crowds in two overflow rooms.

Tonight, standing in jeans and sneakers, Hurwit struggles to finish his first timed run-through behind the lectern. He will argue their state action claim, which alleges that an amusement park was acting for the state when it detained two minors for curfew infractions, in violation of their civil rights.

When he finishes the run-through, the team critiques the substance of his arguments about summary judgment and the coercive effects of the statute. They also critique his style. He should stand up, speak more loudly and make eye contact with all of the judges, rather than just the one who asks questions.

“Should we do another run-through?” asks Nathan Kitchens ’06 from the bench. “We’ve got 20 more minutes.”

Six days

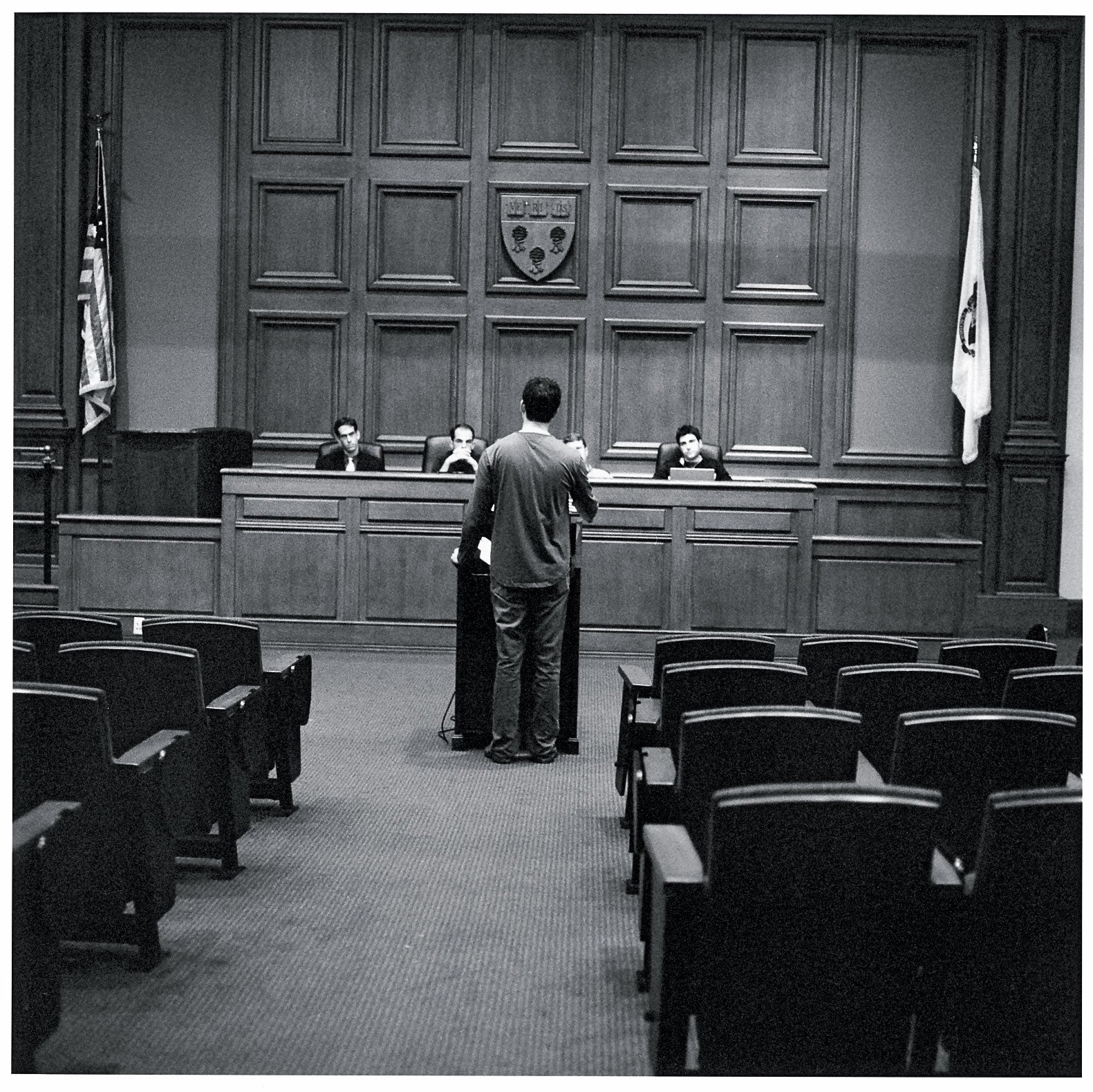

The respondents gather in Ames Courtroom on Friday night. It’s their first time practicing oral arguments as a full team. Adam Harber ’06, the first oralist, stands at the lectern. He’ll defend the legitimacy of the curfew law while the other oralist, Christopher Szczerban ’06, will answer the state action argument.

“May it please the court, my name is Adam Harber,” he begins. He’s tall and he gestures like John Kerry. “Along with my co-counsel–“

He stops suddenly.

“Wait–does anybody remember if I introduce all of you guys or just Chris?” he asks, sounding like a student again.

Just Szczerban, they tell him. Harber nods and again assumes the posture of an orator discussing legal precedents.

“Is this framework really workable?” interrupts Joshua Salzman ’06 a few minutes later. “As Justice Souter here, I wasn’t really comfortable with that framework.”

Harber backtracks and tries to argue his way out of the challenge, but his teammates keep pushing him on nearly every point–his description of the right to free movement, the foundations of the right and hypothetical situations that undercut the petitioners’ claims.

“I’ve been going for like 45 minutes,” he says after a circuitous round of questions. On Thursday, he’ll have less than 20.

Szczerban takes the lectern next, and after a half hour, they’re ready to break for the night. But they’ll be back. The next day–Saturday–their shift in Ames Courtroom will begin at 10:00 a.m.

Back story

The Ames Moot Court competition is a nearly century-old tradition at HLS, started in 1911 through a bequest from Dean James Barr Ames LL.B. 1873. Since 1912, the names of finalists have been memorialized on bronze plaques in Langdell Library–including Harry Blackmun LL.B. ’32, University of Chicago Law Professor Cass Sunstein ’78 and Harvard Law Professor Guhan Subramanian ’98. Previous competitions have brought a stream of “Supremes” to campus, including former Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’56-’58.

The two finalist teams this year have histories of their own. Seven of the 12 were in the same 1L section; one petitioner and one of the respondents are roommates; and both teams have been working to get to the finals for nearly a year and a half.

The process began during their 2L year in qualifying and semifinal rounds, but it kicked up a notch at the beginning of their 3L year in preparing briefs for the finals.

Petitioners say they worked nearly around the clock the final 48 hours before a deadline.

“It’s painful, but it also becomes surreal,” recalls Jordan Heller ’06, remembering the all-nighters and “war room” environment. “The levels of inside jokes and ridiculousness, the junk food that’s consumed–“

“It’s fun in its own special way,” Andrew Cooper ’06 agrees.

Respondents experienced a similar rite of passage writing their brief.

“The night before, we were up all night,” says Harber.

“And the night before that,” adds Ramin Tohidi ’06.

“It was basically different shifts of when people were awake and working on things,” says Szczerban.

They remember it as a delirious week not without its upsides.

“I wouldn’t trade it for anything. We’ve become good friends over this,” Tohidi says. “It’s worth it, given that two of us get to argue before a Supreme Court justice.”

The final week focuses on preparing the speakers, who were picked by their teammates. The petitioners’ oralists will have two additional hurdles. Hurwit, who will speak second, has never competed as an oralist before. And Callahan has an unusual complication: His wife is 39 weeks pregnant. His teammates are well aware that the likelihood she’ll go into labor on or before Thursday increases with every passing day.

Four days

The Sunday before the competition, each team has a four-hour practice in the courtroom. It’s sunny outside–the warmest day in weeks.

Callahan has learned that his wife must have a procedure at the hospital next week, and the doctor’s only available appointment is Thursday afternoon. The procedure risks inducing labor, but the team is not deterred. He keeps practicing as the team’s first oralist.

Just before 2 p.m., when their shift in Ames will end, the teammates decide to move to an empty classroom for more run-throughs. They pack their notes and laptops quickly to avoid an awkward encounter with the other team.

They get as far as the courtyard behind Austin Hall before running into Harber and Tohidi from the respondents.

“What are you guys working on?” Harber jokes.

They stand in the courtyard clutching many of the same case documents, but they seem unsure what to say. After polite but uneasy waves, the shift change is complete.

Respondents take the courtroom and spend the next four hours debating curfew constitutionality and state action. On several occasions, the exchanges become heated.

“You’re very indignant at the thought that we’d look at those two doctrines [joint action and coercion] together,” says Salzman, whom the team has taken to calling “Justice Souter.”

Szczerban stands at the lectern silently.

“I think the petitioners very reasonably asked us to look at all the factors together,” Salzman–aka Souter–continues. “Why are you so opposed to letting us see the whole picture? Is it because you know they add up to a loss for you?”

Szczerban tries again to explain his point, but Salzman keeps pressing.

“Your Honor,” Szczerban begins, addressing a hypothetical that Salzman has introduced. “That’s just preposterous,” he says, breaking into a laugh. “I don’t even know where to begin to answer that question–a dubious curfew statute applied in a preposterous way?”

For a second, the charade vanishes, and they seem like friends in a dorm room again. But within seconds, Szczerban resumes his argument and they plod onward through the late afternoon.

One day away

The teams have one last chance to practice in the courtroom. Callahan stands at the lectern. His wife’s appointment is scheduled for 1 p.m. tomorrow. He seems as calm as ever. (His teammates note that he attended West Point and served in Bosnia and Iraq before attending HLS. They say he has perspective on the stakes of a moot court competition.)

“Can you point me to where respondents agree to that?” Heller interrupts Callahan, insisting that he back up an argument.

“Respondents concede on page 15 that Bellotti is the proper framework for determining in what cases states can justify treating minors’ fundamental rights differently from those of adults,” Callahan says without skipping a beat.

“Is it page 15?” asks an incredulous teammate.

Heller flips through the respondents’ brief.

“It is page 15,” she says, smiling.

Hurwit takes the lectern next. Though he’s been soft-spoken all week, his responses to the team’s questions pack plenty of data–facts, precedent and arguments that reinforce the team’s case.

At 5:15, the respondents enter the courtroom. They exchange hellos and ask about Callahan’s wife, then both teams return to business.

Harber and Szczerban practice timed run-throughs at the lectern. Harber is criticized by teammates for excessive use of the phrase “to the extent that.” And Szczerban admits that it’s the first time he’s been satisfied that he’s covered all the material.

“I want to do it at least twice more tonight,” he says.

Their time in Ames ends, and they move to an empty classroom to keep practicing.

“I think we’re trying to concoct some really, really long explanation that we’re not going to have a chance to get out,” Brian Fletcher ’06 tells Harber after they’ve pored over printouts of legal decisions. “You’re not going to have time to analyze the text of Bellotti.”

In fact, tomorrow Harber will have to condense months of preparation into 17 and a half minutes’ worth of discussion, with judges interrupting with any challenge or clarification they find important. Though the team has tried to prep him by asking every question imaginable, only tomorrow will they know for sure if their practices covered the right bases. They finish several more run-throughs but ultimately decide that sleep will serve them better than a late-night crunch.

Showtime

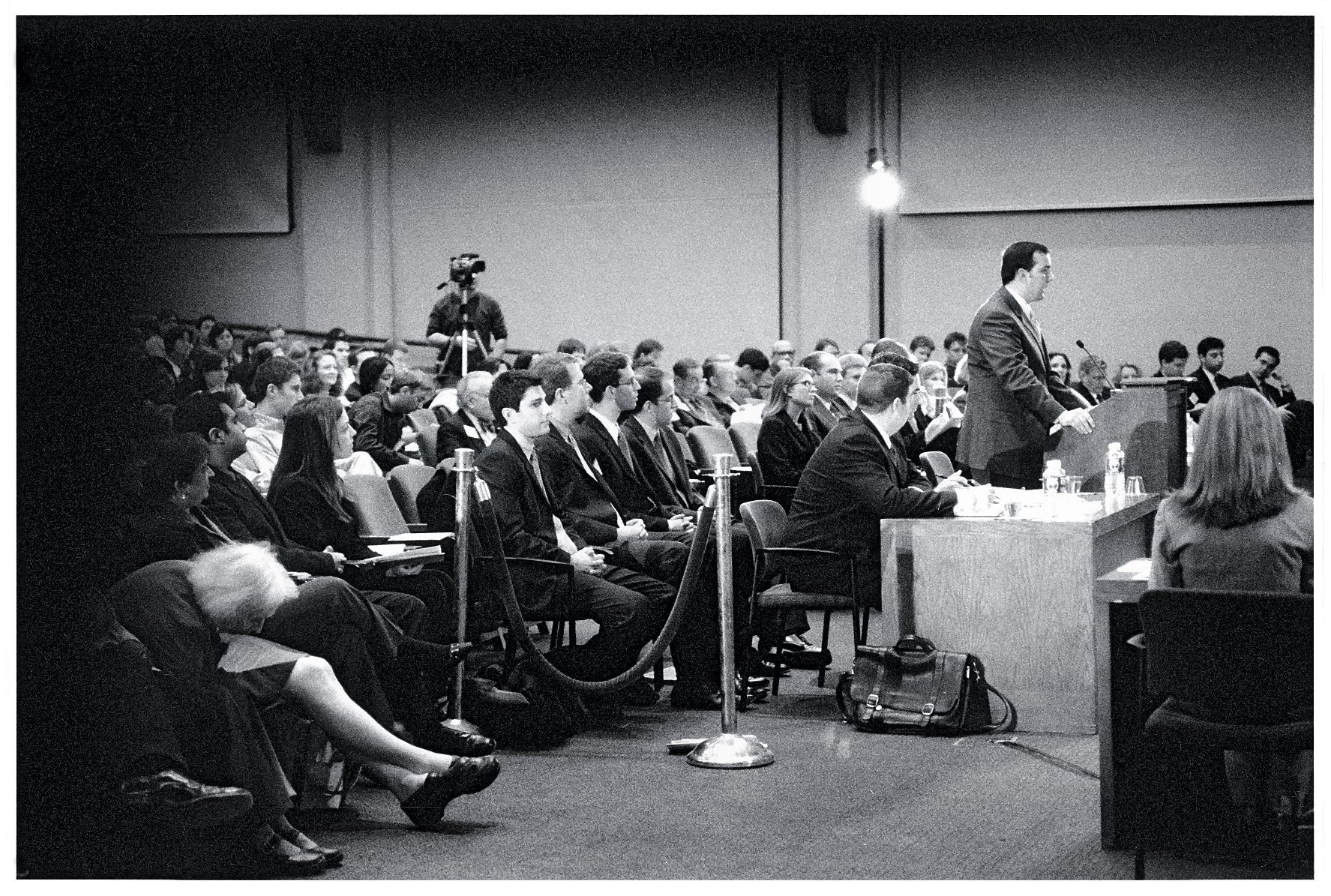

Nearly 275 people fill Ames Courtroom, and the overflow takes up two rooms downstairs. Floodlights, which seem to raise the room’s temperature at least 10 degrees, shine down on the lectern.

“All rise,” says the court clerk, rapping a gavel. “The honorable chief justice and the associate justices for the United States Court of Appeals for the Ames Circuit.”

In their long black robes, Justice Souter, Judge Garza and Judge Rovner take their seats on the bench.

Callahan stands at the lectern in a dark suit. He spent much of the afternoon at the hospital, but his wife did not give birth. He begins his argument, and before the first minute passes, Souter interrupts. The questions are benign at first but become increasingly pointed.

Souter wants to know why legislatures shouldn’t be allowed to distinguish between minors and adults by using a cutoff age of 18.

“Well, how about my question?” he asks, interrupting Callahan’s answer. “You’re telling me reasons you may have for answering my question in a certain way, but I want to know what the answer to my question is.”

The questions for Hurwit are fierce as well. His teammates have coached him all week about speaking up and making eye contact. Their team even videotaped run-throughs so he and Callahan could review their presentations. Tonight, under the lights and behind the microphone, the advice seems to pay off.

He responds with lead-ins like, “It’s true, Your Honor,” to acknowledge the judges’ challenges before rattling off a stream of evidence and precedents to support his argument.

Souter and the other judges are no gentler with the respondents.

“That was not an answer to my question,” Souter says, interrupting Harber. “How about the answer to my hypo?” he presses Szczerban.

Some of the questions focus on points that the finalists barely covered in practice rounds. Several precious minutes are gobbled up when the judges ask about statistical evidence in Harber’s presentation. Much of Callahan’s time is taken up by the interrogation about a cutoff distinction between minors and adults.

By the time the judges file out of the room to deliberate, the participants already seem to have shifted gears–congratulating each other with hugs and handshakes, receiving flowers and applause from friends and family, and smiling for pictures in front of the empty bench.

The judges file back in after nearly 20 minutes, and the room goes quiet again.

The judgment

Justice Souter announces the decision. The respondents win for best team and best brief. Joshua Hurwit of the petitioner team wins for best oralist. But as the two teams congregate for the post-argument reception, the results seem almost secondary to their relief at being done.

“I don’t remember any of it,” says Hurwit, who still seems dazed only an hour after his argument. “I feel like I didn’t get to make any of the points I wanted to make. They were asking me questions I didn’t really know.”

But would he do it again?

“Oh yeah,” he says with a grin. “I didn’t want to leave.”

Coda: Four days later

Bryce Callahan’s wife gave birth to a healthy, 7-pound, 14-ounce girl, Tessa Rose. The team visited several weeks later to congratulate Callahan and his wife, and then went to a Mexican restaurant to celebrate. Hurwit pick up the tab with earnings from his “Best Oralist” prize.