An alumnus from the Class of ’68 enters the Ames Courtroom. The gathering is small, and he smiles at the stranger next to him and remarks that the room has changed since he was last on campus more than 30 years ago. “But then so have I,” he says. “Did I mention I was married back then?”

It’s the first Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Reunion at Harvard Law School. If somehow you missed the news (from the U.S. Supreme Court ruling decriminalizing gay sex, to the decision of Massachusetts’ highest court supporting same-sex marriage, to the weekly hour on Bravo where gay judgment rules), you’d learn from the stories of participants, and the fact that some of them have come back to the school for the first time, just how much the world has changed.

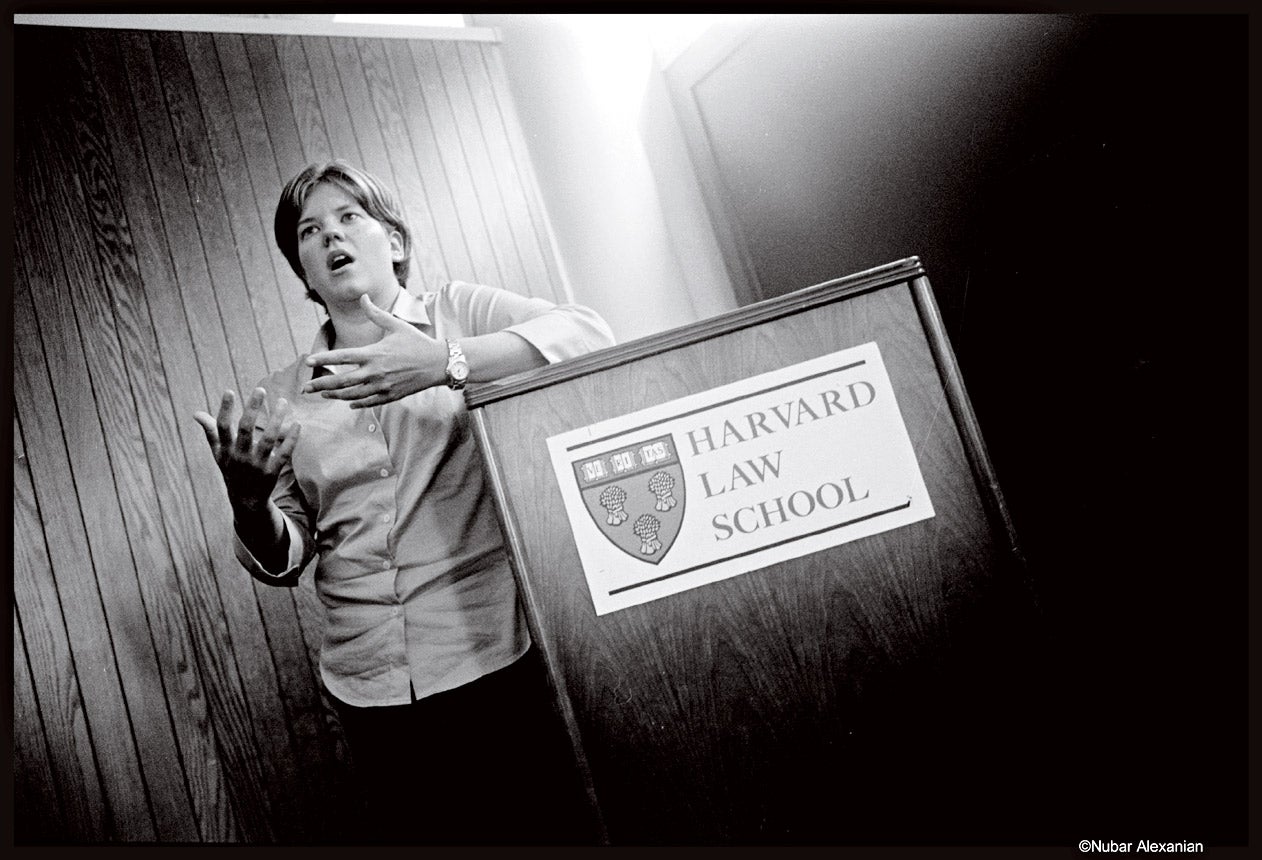

“This weekend was about celebration,” said Sharon McGowan ’00 (pictured above), chairwoman of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Alumni Committee, which organized the event along with HLS Lambda, the school’s GLBT student group. “But it was also about beginning that process of reconnecting with alums who perhaps left Harvard Law School having never thought that it was a place where they could have a meaningful life as an alum and an openly gay person.”

One Saturday last September, more than 70 alumni came back to make that connection. They attended social gatherings, such as dinner with Dean Elena Kagan ’86, and a day of panel discussions, where participants included “out” law firm partners, judges, academics and public interest attorneys, as well as students.

The reunion also marked the 25th anniversary of the school’s first gay and lesbian student organization. José Gómez ’80 (’81) told audience members about the fall of his 2L year, when he’d returned from a summer in a San Francisco gay rights organization intent on mobilizing other gays and lesbians on campus–if only he could find them. Eventually, thanks to his tenacity and “a white lie” that inflated attendance at their first meeting, the Committee on Gay and Lesbian Legal Issues became an official student organization (and soon had at least as many participants as Gómez had described). Over the next two years, members convinced the school to add sexual orientation to the nondiscrimination policy and to cease providing active assistance to military recruiters. But it took several years before all organization participants felt comfortable appearing in a yearbook photo with an identifying caption.

Some things may have changed for current GLBT students; yearbook photos are not an issue. But because of federal legislation, recruiting by the military is. The Solomon Amendment threatens to cut off federal funding to universities that ban the military from recruiting, and the Defense Department now interprets that amendment as applying to policies such as the law school’s. So in the fall of 2002, HLS, like schools all over the country, allowed the Judge Advocate General’s Corps a formal place in the interviewing schedule. Lambda staged protests and organized rallies, where students and faculty spoke out against discrimination.

At the reunion, a panel of gay and lesbian students discussed the galvanizing effects of the amendment. “There’s a difference that I feel post-JAG as to what sexual orientation means at this law school,” said Sarah Boonin ’04, “and not just for gay students.” (After the reunion, Lambda organized a conference on the amendment and lobbied Harvard University to join in legal action against it. In January, 54 members of the law school faculty submitted a brief challenging the Defense Department’s interpretation of the Solomon Amendment and defending the school’s former policy regarding military recruitment.)

Boonin said that, although HLS could do a much better job teaching about sexual orientation and the law, the school is an extremely comfortable place to be out.

Over the course of the reunion, other participants told stories about a time when being gay or lesbian in law school and the legal profession was still an illness to be cured or a crime to be punished–from tales of secrecy and fear to those of activism and celebration.

Geoffrey Upton ’03 interviewed more than 80 GLBT alumni for his third-year paper and is writing a history of the community. He shared excerpts from some of their stories, including the account of a man who came to the school in the late ’60s knowing he was gay and sought help from law school medical services. He was referred to a study at Harvard Medical School, where treatment involved electric shock administered after the student looked at pictures of naked men. The only useful thing that came out of the sessions, the alumnus told Upton, was getting to meet other gay men.

Panelist Allen Schuh ’65, who now runs a foundation that funds work in the GLBT community, hasn’t always been an activist. During his years in law school he was sexually active with other men but kept it a secret from the rest of the world. “We were living in a world where gay men and lesbians were outlaws and couldn’t become attorneys,” he said. He recalled his reaction when in the ’60s he first heard about gay activism: “I was appalled. I thought, Oh, my God. Now they’re going to close the bars.” During the Vietnam War he found himself put in charge of “court-martialing people like myself.” He later practiced in a Chicago firm, where eventually the other partners knew he was gay, although he never talked about it. “But then the epidemic changed everything,” he said. After his partner contracted HIV, Schuh retired from practice, and he now runs the grant foundation his partner set up before he died. “I used to think that public service involved sacrifice,” said Schuh, “but it has been the most fulfilling part of my life.”

A discussion of life at law firms today portrayed a very different world for more recent graduates. Morris Ratner ’91, a partner at Lieff Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein in its San Francisco office, said his biggest challenge at the firm is “to build meaningful relationships with people who aren’t gay.” Mark Smith ’86, a partner at Testa, Hurwitz & Thibeault in Boston, says he’s been out at his firm for years. Some attorneys simply require a little work, he said: “You know, queer eye for the straight partner.”

Panelists reflected that their experience wasn’t necessarily representative since they had no doubt “self-selected” firms where they could be comfortable. But Kirstin Dodge ’92, a partner in the Bellevue, Wash., office of Perkins Coie, said such selectivity is important, and that being out in interviews is a good place to begin.

Not all participants agreed. But Judge Deborah Batts ’72 of the Southern District Court of New York, the first openly gay federal judge, said when she has to look through 400 to 700 applications for clerkships, it helps if people can give a sense of themselves. And she believes she is not alone:

“The biggest problem I have is trying to get to the LGBT candidates before the other judges do.”