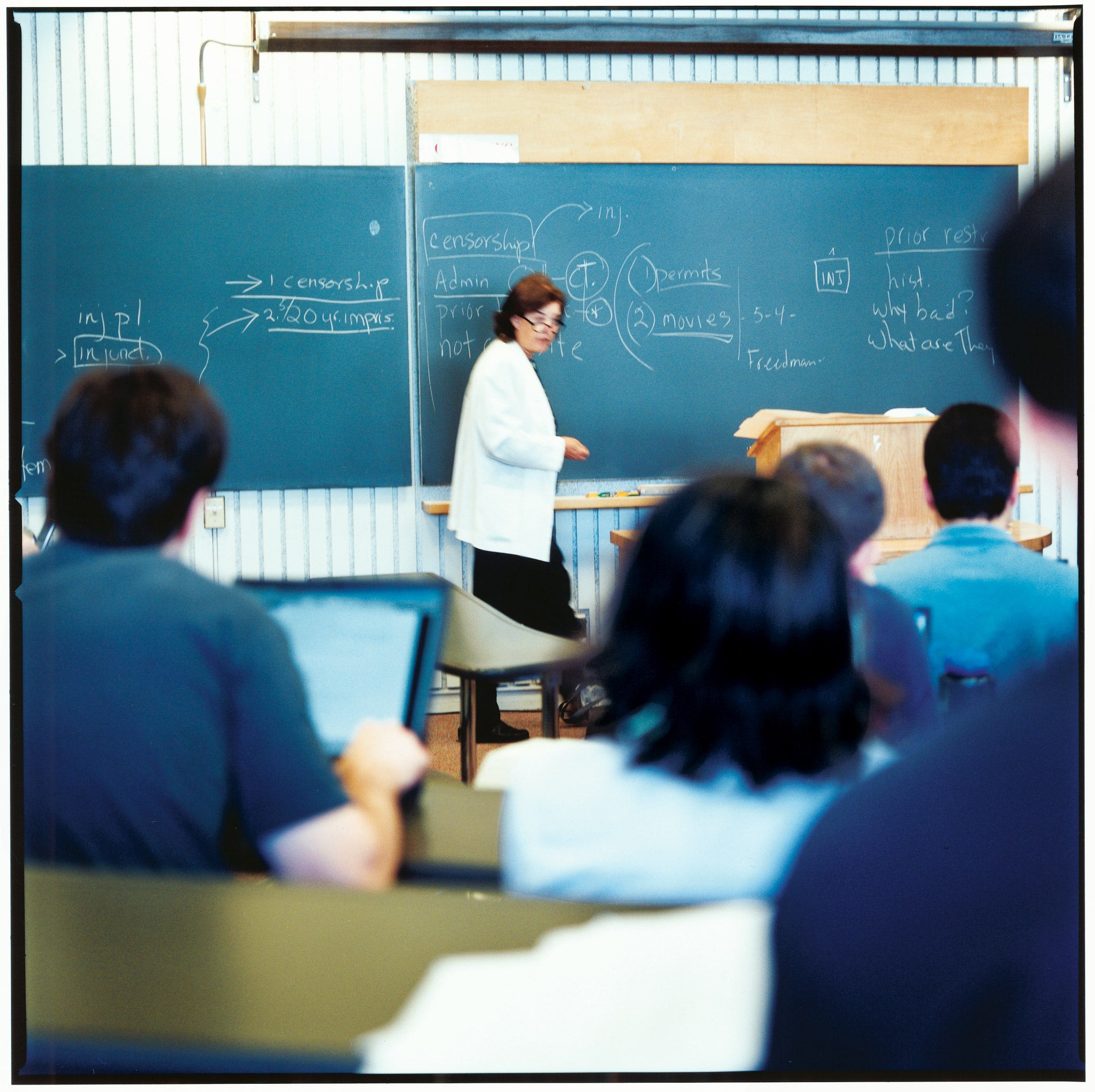

HLS wasn’t an easy place for its first female professors–with over 150 years of tradition that did not include them. Today, women faculty have transformed the school beyond their numbers, through their contributions to the classroom and their fields.

Yearbooks tell the story of who we were and who we wanted to be. Look back to 1972, at the faculty photo, where rows of men are joined by one woman teaching fellow who’s put down her leather bag to join the tenured ranks until the shutter clicks. Flip to the article by 1L Marley Weiss decrying “Harvard’s pervasively male atmosphere and orientation.” Part of the problem, she wrote, was the lack of female professors: “In terms of providing non-sexist classrooms, sympathetic faculty ears, and role models for future women lawyers to emulate, the female faculty member is indispensable.”

For years, this was a familiar story for women students and graduates. Even beyond the classroom, they’d found few female role models or mentors in the law firm, the courtroom or the boardroom. But the world was changing, and by the summer of 1972, HLS changed too, granting a woman tenure for the first time.

Today it’s the same school, but a different picture. Women make up 45 percent of this year’s graduating class, and the curriculum includes courses taught by men and women that touch on gender issues. As for women on the permanent faculty, the number has risen to 15 (12 of them tenured). By now, Weiss is a professor at the University of Maryland School of Law. And Professor Elena Kagan ’86 is about to become Harvard Law School’s next dean, turning the page on a sometimes difficult history.

* * *

In 1947, Visiting Professor Soia Mentschikoff–one of a handful of women law professors in the country at the time–became the first to teach at HLS. She went on to the University of Chicago, and 25 years passed before international tax scholar Elisabeth Owens became the first woman to get tenure at HLS. During the ‘ 70s, other women taught at the school (Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’56-’58 was among them in 1971, the year before she joined the Columbia faculty). But it wasn’t until 1979, after Dean Albert Sacks ’48 offered University of Pennsylvania Law Professor Martha Field a faculty position, that Harvard counted another woman professor among its tenured ranks.

Field’s first encounter with the hiring process at HLS wasn’t encouraging. In 1968-69, when she was the only woman clerking on the Supreme Court, she heard HLS had arranged for interviews for prospective faculty. All clerks were invited to interview, “except for the girl.”

“I’m a sufficiently ornery person that that may be why I ended up at Harvard,” said Field.

As the only woman faculty member at Penn for years, Field had gotten used to the challenges: the male students who asked why they hadn’t gotten a real teacher or offered to help her with her lectures. At first, when she came to HLS, there was a bit more of the same. “You just developed a tougher skin,” she said. “You’d always have something to say back to them.” Field has taken the same tack since, when she has objected to HLS politics or policies: “I’ve always felt it was my role to be outspoken and consciousness raise.”

When HLS did make Field an offer, Sacks reassured her that she would continue to teach Federal Courts and Constitutional Law. “I did appreciate it,” she said, “because I wouldn’t have come here to be their token woman.”

* * *

Professor Elizabeth Bartholet ’65

Elizabeth Bartholet ’65 went to law school because of her interest in civil rights and public interest work. When she became an assistant professor in 1977, it was after 12 years as an attorney, including a stint at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and five years at a public interest organization in New York City, which she founded and led.

Like Field, Bartholet says all of her professional life, she’s worked in a predominantly male world. Her days as a student at Harvard Law School had introduced her to this environment. She remembers a torts professor who always used knitting or sewing hypotheticals when he asked her a question. “The presence of women,” she said, “was treated as an awkward situation that they could joke about because that was the way to deal with the discomfort.”

But for the women of Bartholet’s generation, compared to the professional world, law school had been a haven. Comparative law and constitutional scholar Professor Mary Ann Glendon says after she got her J.D. from the University of Chicago in 1961, “Discrimination was right out there in the open.” She recalls a partner at a law firm in New York City telling her he couldn’t hire her because he couldn’t bring her in to see the president of IBM any more than he could bring in a Jew.

Despite having been an editor on the Law Review and ranked 12th in her class, Bartholet found that most judges were unwilling to hire her, and leading prosecutorial offices had policies against hiring women. And once she was working, there remained the extra burden of proof: “You still had to convince judges, and lawyers on the other side, that you were serious and effective and that they couldn’t just get away with bullying you or brushing you aside.”

Bartholet, like Field, found the early years at HLS isolating–but she says that was largely because she came from the activist world, where she’d experienced a more collegial atmosphere and colleagues who shared more of her values. The difficulties that women on the faculty faced in the early era are subtle and hard to define, she says, but had to do with that extra burden women had to shoulder to be taken seriously.

“I feel that, as a general matter,” said Bartholet, “from the time I first came here, women, as well as other suspect characters–such as African-Americans, Hispanics, other racial minority group members–have had to perform better in the classroom and outside the classroom to get equal treatment.”

Yet the opportunities for teaching, research and public policy advocacy made Bartholet want to stay. Most recently, she’s focused on reproductive technologies, adoption and child welfare. “It is an extraordinary luxury,” she said, “to have a job where you have as much freedom to define your intellectual agenda and how you will pursue it as you do here.”

Promoted in 1983, Bartholet says she has the distinction of being the first woman to have survived the tenure process.

By that time, a wave of new young assistant professors had arrived, including three women: Martha Minow, Susan Estrich ‘ 77 and Clare Dalton LL.M. ‘ 73, followed by Kathleen Sullivan ’81 in 1984. Glendon joined the faculty from Boston College Law School two years later.

Estrich, who is now a professor at the University of Southern California Law School, recalls being tried and tested at HLS, both as a student and when she returned as a professor. “The best way to deal with it was by being tough and good-humored,” she said. “But that didn’t make it easy.” In addition to the challenges that she faced as a professor, she was frustrated to see how female students were faring. “In the early years, especially, it was like pulling teeth to get women to talk in class,” she said. “I was disappointed to find that, in my large classes, my grading of students followed the same pattern as everyone else’s: men on top, women clustered above average. But the magnas were almost all men.”

Sullivan, now dean of Stanford Law School, describes the difficulty many of the older male professors had getting used to women colleagues. In an essay included in “Pinstripes & Pearls,” a new book by Judith Richards Hope ’64, Sullivan writes that, at first, male faculty had a tendency to lump women colleagues together, calling them all Martha. “The faculty library had two small bathrooms, but neither was marked Women,” she wrote. “We managed to rectify that only after we suggested that one be marked Men and the other Martha.”

When the new crop of assistant professors came up for tenure, several male colleagues were promoted. Dalton, a feminist legal scholar, was turned down. She sued for gender discrimination and Harvard eventually settled, funding the startup of a domestic violence program at Northeastern’s law school that Dalton now runs.

Bartholet says she saw the Dalton case as involving both gender discrimination and political discrimination. And she believes the tensions that emerged among the faculty then still exist today. “But the fact that there are political and other debates and differences within a faculty is probably more of a plus than a minus for students,” she said. “It makes this place a much more interesting intellectual environment than it was when I was a student here and the faculty was quieter and more homogenous.”

Glendon says Dalton’s conflict with Harvard resonated with her as the struggle of a woman academic with young children, a struggle Glendon too had faced. From early on, trying to make family fit with their professional aspirations has been part of the challenge for women faculty.

Credit: Kathleen Dooher Assistant Professor Margo Schlanger with 3L ReNika Moore

Field, who has three children, describes squeezing her pregnancies in around her teaching in the early days before schools granted maternity leave, let alone parenting leave, which is in place now at HLS for women and men. Bartholet remembers having to convince the administration in the ’80s that adopting a baby warranted the same parenting leave as giving birth.

Margo Schlanger, an assistant professor who began teaching at the school in 1998, says she feels grateful to her predecessors who made it a more hospitable place for women.

It used to be common wisdom to wait to have children until you were professionally established, says Schlanger, who, with her husband, Assistant Professor Samuel Bagenstos ’93, is the parent of 3-year-old twins. Schlanger hopes that the recent example of women professors who were promoted after they had children means the environment has changed.

* * *

As far as the environment for women students at HLS today is concerned, the days of sewing hypotheticals are long gone. “Women students have political power by virtue of their numbers,” said Bartholet. “And I think that is significantly true for racial minority groups as well.”

Over the years, students have made their voices heard, asking, among other things, for a more diverse faculty. During Dean Robert Clark’s deanship, 12 women were hired–doubling the percentage on the faculty from 9 percent in 1989 to 18 percent today. Among them is Lani Guinier, the first and only black woman faculty member.

Renée Dall ’03, co-chairwoman of the Women’s Law Association and co-editor of the Women’s Law Journal, says these numbers are still too low. For mentoring purposes, women faculty, she says, are spread too thin. “It is nice to have people who are in some way like us,” she said, “and to speak with them of balancing work and family or about being a woman in a structure that is so male-dominated. It gives us hope and reassurance.”

Dall also wishes there were more discussion of gender and race in the classroom. Guinier teaches a seminar called Critical Perspectives on the Law: Issues of Race, Gender, Class, and Social Change. But in every class, her goal is to develop ways of teaching that serve her students–all of them. Guinier joined the HLS faculty in 1998 from the University of Pennsylvania, where she’d observed and written about how many women law students do not thrive on the traditional approach to legal training. And this, she says, is not a sign of a problem with women, but an opportunity to improve the learning environment for everybody.

“Now that we have a much more diverse group of faculty and students, this may be a moment to reflect on other ways of engaging students in an equally rigorous intellectual environment that meets not only the needs of the students but the needs of the profession in the 21st century,” she said.

Besides developing alternative approaches to teaching in her own classes, Guinier has held a series of workshops in which other faculty are examining their pedagogy. It started as a response to the incidents in the spring of 2002 among students and in the classroom that involved conflict around race. Guinier says they began by focusing on how faculty handle issues of race or gender in the classroom and how students of color and women respond. “But a conversation that seemed to be generated by the concerns of a particular group,” she said, “has allowed us to think critically and reflect in an ongoing way about how we teach everybody.”

Guinier has written that she prefers to think of herself as a mentor rather than a role model. She takes issue with the idea that people necessarily model themselves on a person of their own gender and racial or ethnic group. And she is interested, she says, in reaching all her students, not simply those who share her identity.

The same caveats apply to the ambition and interests of women faculty as a whole.

Schlanger, for example, points out that, while she is the only female member of the faculty teaching torts, she is not the only person teaching about gender and torts–male professors do as well. She also teaches a seminar on gender and race discrimination, although she is white. “Is it because we have women on the faculty that we have classes that talk about gender discrimination?” asks Schlanger. “Maybe. Or maybe it’s because we’re a faculty that takes a norm of equality seriously that we both have women on the faculty and classes that talk about gender discrimination.”

Although Field and others still believe that there are not enough women faculty at the school, clearly those who are here are transforming it beyond their numbers, through their contributions to their fields and to their students.

Joining professors like Martha Minow, international scholar on war crimes and refugees, women faculty hired during Clark’s deanship include bankruptcy expert Elizabeth Warren, who like Guinier received the Sacks-Freund Teaching Award, in her case recognizing her Socratic teaching style; Janet Halley, an authority on legal issues surrounding gender, identity and sexual orientation; Lucie White ’81, who teaches social advocacy in the classroom and in clinical settings; legal historian Christine Desan; death penalty expert Carol Steiker ’86; tax scholar Diane Ring ’90; employment law expert Christine Jolls ’93; and election law and voting rights scholar Heather Gerken, as well as the law school’s next dean, administrative law expert and former White House lawyer Elena Kagan.

Under her leadership, who knows what the picture will look like?