Two new books offer different views on what America watches, and what children are not supposed to see

Alfred Schneider ’52 graduated from Harvard Law School a passionate First Amendment defender, a “strict constructionist in the interpretation of free speech.” In his new book, he champions free expression and details his zeal to do everything is his power to ensure that controversial, groundbreaking material is aired.

Alfred Schneider ’52 graduated from Harvard Law School a passionate First Amendment defender, a “strict constructionist in the interpretation of free speech.” In his new book, he champions free expression and details his zeal to do everything is his power to ensure that controversial, groundbreaking material is aired.

He, in case you were wondering, is the censor.

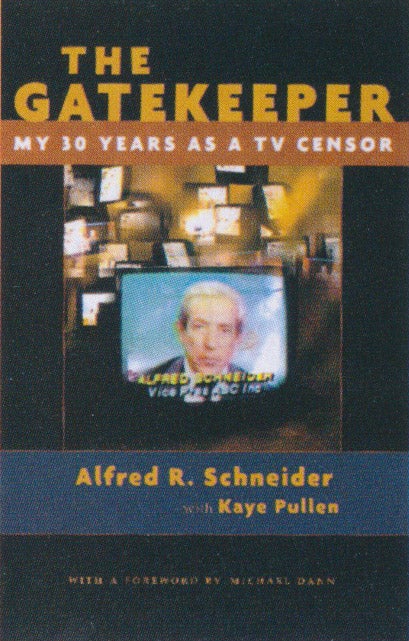

Schneider pursues the role not unlike Nixon going to China: a person ostensibly unsuited for the task but making the most of it for that very reason. In The Gatekeeper: My 30 Years as a TV Censor, Schneider recounts his career as vice president for policies and standards at ABC from 1960 to 1990, years of tumultuous change in the nation and on its TV screens. The job, unique to the broadcast medium of television, balanced the responsibilities of a government licensee and the necessities of a profit- and advertiser-driven business. While lobbied by groups–from gay rights advocates to the religious right–that wanted to shape network programming to their own agendas, Schneider envisioned the television censor as foremost “a guardian of the public interest.”

At the same time, he understood that the creative community must have an opportunity to innovate. He shepherded through production the TV movie Something about Amelia, which dealt with incest; The Day After, a TV movie that portrayed the aftereffects of a nuclear attack on the United States; and Soap, which featured the first openly gay major character in a network television series.

Schneider of course did censor also. In his book, he recounts many battles, including one in which he nearly came to blows with Danny Arnold, the creator of Barney Miller, over Schneider’s refusal to allow the words “hell” and “damn” to be used on the series. Though that debate may seem quaint now in an era when the word “asshole” is uttered on the same network he worked for, Schneider writes that his work reflected mainstream values of the times.

“As I looked at how I approached the portrayal of violence, the expression of love and sex, and the intertwining of the breaking of taboos in this three-decade review, I realized that television is the diary of our lives. Television programming is ultimately the culture.”

He never anticipated, as his career began, that he would play a part in shaping that culture. After graduating from HLS, Schneider took a job at ABC, eventually advancing to become the assistant director of business affairs, and he later worked as assistant to the president at CBS. Schneider returned to ABC in 1960, accepting a newly established position formed in reaction to the quiz show and payola scandals that rocked the industry.

“My job was to see that we succeeded as a network,” Schneider said in an interview with the Bulletin. “I had to review the program in such a way that we didn’t cast off the program. At the same time we had to do it in a way that the advertiser would support it, and therefore you exercise a review of the degree of sexuality and violence and [consider] how much the advertiser would hear from the viewer. And the fact was that you had a license at stake. There was a great deal of government regulatory process.”

Through his 30 years on the job, Schneider saw plenty of sex and violence. His network ushered in the debate, still raging, over mass-produced violent entertainment, with series like The Untouchables in the 1960s. The ’70s introduced “jiggle TV,” with shows like Charlie’s Angels and Three’s Company increasing viewership on ABC but also increasing calls to restrict sexual content. Loftier–and even more controversial–themes emerged in that era too, with the medium’s first airing of subjects such as homosexuality and abortion. And Schneider worked in the trenches, tweaking scripts and storylines, cajoling and beseeching the creative talent to allow him, as he writes, “to act responsibly, to preserve a sense of fairness and good taste, to respect the dignity of man, to balance interests that the medium serves, to permit the exploration of new ideas and examination of old practices.”

The pushing of boundaries has continued in television without his stewardship, though, this censor said, not nearly enough.

“I miss the fact that there is not more of the controversial issue material of The Day After and Something about Amelia, the programs that dealt with the issues of our times dramatically,” said Schneider. “I think that’s a loss.”

The function of a gatekeeper as he molded it may too be lost, said Schneider. Although he makes the case in his book that the TV censor role should continue, he believes it will disappear in the next five years. Schneider has thus written the first book by a television censor and perhaps the last. The Gatekeeper may spark debate among First Amendment absolutists and cultural warriors, but Schneider does not doubt that this once reluctant gatekeeper fulfilled an important if misunderstood function.

* * *

Marjorie Heins ’78 would consider censoring a work that has been proven to harm children. She just hasn’t found one yet. And, boy, has she looked.

In Not in Front of the Children: Indecency, Censorship, and the Innocence of Youth, Heins uncovers a pattern of censorship throughout history, all justified by the need to protect children. In each case, the underlying assumption that adults should shield children from certain books, images, and speech is rarely questioned. But Heins does, and finds the ultimate straw man in the debate over the limits of the First Amendment.

Heins, director of the ACLU Arts Censorship Project for eight years, helped litigate Reno v. ACLU, which challenged the 1996 Communications Decency Act. Currently director of the Free Expression Policy Project of the National Coalition Against Censorship, Heins was inspired to write the book by her own experiences fighting censorship. Yet she also approached the subject without an agenda, she said. And she buttressed her conclusions with copious research (the book contains more than 1,000 footnotes) and a measured approach to a subject that has defined her career.

“What became increasingly apparent to me was that frequently the justification for the censorship initiative was the kids,” she said. “Sure, we have the First Amendment for adults, and adults were presumed to somehow make their way through the marketplace of ideas, but kids have to be protected or shielded or censored and not allowed to have access to some kinds of art, entertainment, and ideas. It was always assumed that this was a legitimate, compelling government interest.”

In her book, Heins details judicial decisions that deny First Amendment rights for the sake of children. Though in the guise of protecting children, the decisions often served to restrict adult access, she writes. They include FCC v. Pacifica, or the “seven dirty words” case, which allowed the FCC to ban the broadcast of George Carlin’s scatological monologue about forbidden language. Justices have also betrayed a paternalistic attitude, according to Heins, as evidenced by Justice Warren Burger’s fear in the Bethel School District v. Fraser case that a student’s risquÈ speech at an assembly would offend the sensibilities of young females in the audience.

These cases follow a tradition of censorship arguments, which Heins charts from the days of Plato. The philosopher urged a ban of the written description of the gods’ erotic activities because it would “engender laxity of morals among the young.” That sentiment was advanced by Anthony Comstock, the infamous American censor who warned that there is “no more active agent employed by Satan in civilized communities to ruin the human family than evil reading.”

Though many Americans and their legislators even today may agree with Plato and Comstock, Heins contends that social scientists have never proven that any identifiable subject has changed children’s behavior in a predictable manner. “Provocative ideas in art or entertainment do affect the human psyche in myriad ways,” she writes. “It is just that these effects cannot be quantified.” In addition, according to Heins, materials designed for children–movies such as Bambi and stories such as Treasure Island–can frighten youngsters more than so-called “adult” material. But few would campaign to censor Disney movies.

Heins does not argue that unfettered access to all forms of expression would benefit children. Even as some studies have claimed that violent images may help create violent children, Heins cautions against simplistic conclusions. “When you look at it, the definitions of violent entertainment are all over the lot,” she said. “There’s very little attempt to put violence in context, so it would be impossible to frame any kind of censorship legislation that would pinpoint what the harm is.”

Rather than “intellectual protectionism,” Heins advocates media literacy programs and sexuality education to help children cope with their surroundings. She also questions the efficacy of “forbidden speech zones,” which may attract children to the very material that adults would deny them. Better, she said, to teach children to make the best choices than to pretend those choices don’t exist.

“Kids are going to make some choices about culture, and those choices can be influenced by their interaction with their parents and their teachers,” said Heins. “It’s sort of similar to food. I think when your kid is a baby you can feed them good healthy baby food. Once they get into nursery school, they’re going to start learning about the other temptations, so the most parents can do is to try to continue to make some rules and try to explain why they’re the right rules.”

Heins concludes that concerns about violence, language, and sex “have more to do with socializing youth than with the objective proof of psychological harm.” Censorship on behalf of children, she believes, is really done for the adults who demand it.

The Gatekeeper

The Gatekeeper

My 30 Years as a TV Censor

by Alfred Schneider ’52

Syracuse University Press, April 2001

Not in Front of the Children

Indecency, Censorship, and the Innocence of Youth

by Marjorie Heins ’78

Hill and Wang, May 2001