Both sides have advocates as Harvard University considers moving HLS

Dennis Thompson has been thinking about this for four years, thinking about this longer and harder than most anyone else. So he can be forgiven, amid committees and consultants and the deliberate pace of academe, for dreaming a big dream. He sees rising out of fallow land an education nirvana, a place where people will study and research and teach and live and that they will relish for all the opportunities and comforts it affords.

The place is Allston, Mass., the focus of a Harvard University planning committee that Thompson chairs and, increasingly, the focus of the dean, faculty, alumni, and students of Harvard Law School. For the University Committee on Physical Planning is looking not only across the river but across the Yard at HLS, which could be the linchpin of a new professional school campus that could include Harvard’s graduate schools of law, business (currently the only Harvard school located in Allston), government, education, and design.

“My own hope is that we will make it so attractive and so exciting that everyone will want to move there,” said Thompson, a professor of political philosophy and senior adviser to Harvard President Lawrence Summers. “We want to see individual faculty and whole schools competing for a place in Allston.”

That hasn’t happened yet. Indeed, the initial HLS faculty opinion was resoundingly negative, with the faculty voting nearly unanimously in the fall of 1999 for the law school to remain on its Cambridge campus. While many faculty still don’t favor such a move, some have warmed to the idea of designing a law school campus to suit the pedagogical and space needs described in the school’s Strategic Plan. All agree that the current configuration of the campus will not serve those needs. And for Dean Robert Clark ’72, physical locale is less important than continuing the tradition of excellence at HLS, wherever it may be. “I don’t have any deep passion about a location or space,” he said. “I have a deep passion about the law school being the best institution for learning about law and legal institutions in the world. I want to do what’s right, and we’re trying to figure that out.”

Ultimately, the future home of Harvard Law School will be determined by Summers, who embraced development of the Allston campus in his inaugural speech last year, and the Harvard Corporation, the top governing body of the university.

“I cannot tell you where this process will end up,” Summers wrote in a statement to the Bulletin. “I can tell you that it will be a process that will consider all options and one that will involve enormously careful deliberation and wide consultation with the purpose of arriving at a scenario that is acceptable to all involved. I have no doubt that Allston planning will continue to exhibit a strong collaborative spirit.”

University officials are currently considering only one other possibility that would likely supersede the move of the law school: a science park that may focus on biotechnology and would, they hope, rival Silicon Valley for research and innovation. A cultural complex, including Harvard’s museums, would likely supplement either a science or professional school campus. But before they make a decision–which may not happen for two years or longer–they will hear from a Harvard Law School committee that will attempt to outline the positives and negatives of moving the law school to Allston.

Established by Dean Clark in November, the Locational Options Committee is scheduled to issue a report this fall. (The Bulletin will report on the committee’s findings after they are released.) The committee, chaired by Professor Elena Kagan ’86, will not offer a recommendation but has gathered facts and opinions from the many constituencies that have a vested interest in the decision.

The faculty rejected the proposal to move in part due to its connections to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS). Some faculty members bristled at the description of HLS as a professional school. Though certainly a training ground for lawyers, HLS, they say, also focuses on the academic study of law, often intertwined with disciplines such as economics, history, sociology, and other subjects linked to the intellectual life of Harvard Yard.

Calling Harvard Law a professional school is accurate, says Professor Frank Michelman ’60, “but it doesn’t fully capture what we do or what we are here to do. The law faculty has become the academic center within the university for what people sometimes call legal studies, looking at the activities of law and legality in society in general and our society from outside as well as inside the profession. If there is on this campus any place that serves as a focus for that, it’s this place, this faculty.”

Kagan said, “If you did have the business school and us and the Kennedy school and a couple of other policy schools like the ed. school in Allston, there could be new academic connections. But there are very significant issues here about where legal education is going and what are the most important ties for a law school.”

Another factor that will influence a decision to move is the potential growth of the law school. The school’s Strategic Plan calls for more faculty and research, more interdisciplinary training, more technology, more of an international reach. Looming over it all, however, is the need for more space. The campus, according to the plan, requires an additional 115,000 square feet merely to accommodate its existing needs, and must add at least 300,000 square feet to carry out the new initiatives of the Strategic Plan.

During the most recent academic year, the school implemented a major component of the plan: reducing first-year sections from approximately 140 to 80 students. Yet the campus in its current configuration does not have classroom or meeting space designed for the new sections, envisioned as law colleges, or for other facets of the plan.

The school is scheduled to launch a fund-raising campaign next year to support academic initiatives of the Strategic Plan. Currently, the facilities component of the campaign is aimed at building a new quad–subject to City of Cambridge permission–after putting the Everett Street garage underground and moving the wood-framed houses that are now on Massachusetts Avenue near Pound Hall. If the university decides that the law school should move to Allston, HLS will likely seek building funds for use at the new campus. Plans for a new quad in Cambridge would still go forward, with university financial support, to serve the law school’s interim space needs and later be converted to university use.

Even if the law school gets all the space it seeks, it still may not be enough in the long term, says Dean Clark.

“If we stay here in Cambridge, we’re going to probably get into serious trouble, even under the best projections, in 20 years,” he said. “If the law school were moved to Allston and got, as it would have to, I think, significantly greater acreage, it could probably take care of its growth needs for 50 years, and perhaps much longer. Growth potential is a big factor in the decision.”

Law School Views

When Dean Clark considers the possibility of leaving the current campus, he, as much as anyone, understands what would be left behind. Just a few years ago, he devoted himself to a campaign that raised over $30 million to refurbish Langdell Hall, the law library that is widely acknowledged to be the best in the world.

Some graduates point to alumni donations for the library and the campus, including the creation of Hauser Hall in 1994, as a principal reason to remain on the Cambridge site.

“It seems a lot to ask perhaps for all the benefactors of the school to walk away from the investment and leave it for the college or some other part of the university and in effect to start all over again,” said David Landrey ’69.

When Dean Clark announces the possibility of the move at alumni gatherings, invariably someone in attendance asks about finances. It is a question without a specific answer yet. He expects, however, that the university would make “full and fair compensation” to the law school for giving up its land and its buildings.

A new campus would replace one whose buildings–besides Langdell and Austin Hall and perhaps Gannett House–are seen as utilitarian at best. Yet many in the HLS community treasure not only the showcase buildings of the campus but the sense of history and grandeur that pervades it.

Attending Harvard Law School may be less meaningful at a different campus, some say. And no matter how large and functional new buildings may be,they would not likely match the luster of what would be left behind.

Finn Caspersen ’66, chairman of the Dean’s Advisory Board and the upcoming HLS fund-raising campaign, hears similar sentiments from other alumni: an emotional attachment to the buildings and the memories of the law school. And it’s difficult for him, he says, to imagine the law school without Langdell. Yet he is intrigued by the Allston possibility.

“It’s a fascinating concept to actually be able to design a graduate center with the dormitories and the library and classrooms–and to do so based on what’s best for the education, what’s best for students and faculty,” he said.

Many other loyal donors with strong ties to the school would support and contribute to a new campus in Allston, according to Dean Clark. “Some of our alumni leaders think that it’s a great new opportunity,” he said. “It will inspire a lot of people to get in on the creation of something wholly new.”

A new campus could foster one of the primary goals of the Strategic Plan–building a closer-knit community at HLS, said Professor Anne-Marie Slaughter ’85. She cited the University of Chicago Law School, where she taught, and NYU School of Law as institutions that concentrate academic activities largely in one area. “It makes a huge difference both because of faculty interaction but, equally important, faculty-student interaction outside of class, so that you are running into your students, your colleagues, the administrators–you have a physical sense of being a part of one community,” she said.

The director of the school’s Graduate Program, Slaughter said a new campus could better integrate the mostly foreign LL.M. and S.J.D. candidates with the J.D. students. If the law school were close to the Kennedy school and business school, which have a higher percentage of foreign students and disciplines that are more global than those at HLS, an oft-stated Harvard goal of internationalization could blossom, she said.

Professor Janet Halley cautions, however, that a campus in Allston could damage a sense of community. She also cited her own experience, as a professor at Stanford Law School. The school’s remote suburban location in Palo Alto, she believes, led to faculty spending much of their time working at home, empty corridors and offices during the day, and a lack of programs and speakers in the evening and on weekends. HLS is more vibrant than Stanford, a major factor in her relocation, she said. “Its urban location and proximity to the university make it a challenging place, where working with and learning from others is an important part of institutional life,” she wrote in a letter to faculty members. “I worry that relocating the school away from the university would put that vitality at risk.”

Many students share that concern. Yet a new campus, most observers say, would primarily benefit students, who often complain of substandard housing, athletic facilities, and space for student organizations. Mike French ’02, the Law School Council president during the past year, fielded many of those complaints throughout his three years on the council. He favors a move to Allston, citing the business school facilities as a standard that HLS should meet for its students.

“My first reaction was, why would you move when you had all these buildings and a great location,” he said. “Knowing more about the school, knowing more about the challenges facing the Gropius housing complex, and also knowing more about what modern architecture could provide, having seen other schools and other campuses here at Harvard, that’s pushed me towards a move.”

French’s successor on the council, Bill Dance ’03, sees the benefits too. Indeed, his own experience represents a major argument for the move: Because of schedule conflicts among Harvard’s schools, he cross-registered at MIT’s Sloan School and not Harvard Business School. A cohesive graduate school community would serve many students, he said.

Yet Dance is wary of Allston, a sprawling neighborhood that reminds him of his native Los Angeles. For him, that’s not a compliment. The presence of the business school, he said, has not transformed the neighborhood into an oasis for students. And his own quality of life as a graduate student would have been diminished, he believes, if he had opted for Harvard Business School rather than HLS.

“If it were simply would you rather be in Cambridge or Allston, then definitely Cambridge,” he said. “If it were even keeping the buildings we’ve got and building more and repurposing for the dorms, I’d still rather the school would do that. But if they can’t do those things, it makes a much stronger argument for Allston.”

The negativity about Allston often voiced in Cambridge is understandable but also unfair, said Dave Friedman ’96, who sees the issue from both sides, literally. An HLS grad, Friedman also is running for state representative in a district that includes Allston. “It’s understandable because Harvard Square is such a great area,” he said. “As a law student I loved Harvard Square, and I think a lot of people who are law students would miss that area, but it’s unfair because Allston has a lot to offer. Allston-Brighton is actually really a great community that’s very diverse and has a lot of hidden treasures. . . . I think the moving of the law school has the potential to be very positive for the community and for Harvard.”

Yet for many students, Cambridge and HLS are an inseparable pair. In fact, according to former Harvard Law Record editor Meredith McKee ’02, most of the students she spoke with while reporting on the issue want the school to stay.

“The vast majority of comments that we got tended to be against the idea [of moving] or skeptical,” she said. “You get a lot of complaints about facilities, but whenever push comes to shove, I think a lot of students like being near Harvard Square and really like the location. And, to my surprise, a lot of people are seemingly tied to Langdell.”

Students need to know that the school would leave Cambridge for something better, they say. Or, as Laura Mutterperl ’02 put it, “You can dangle all these facilities, but you’re taking away everything we have in Cambridge. How can you replicate everything that is built up here down there?”

University Planning

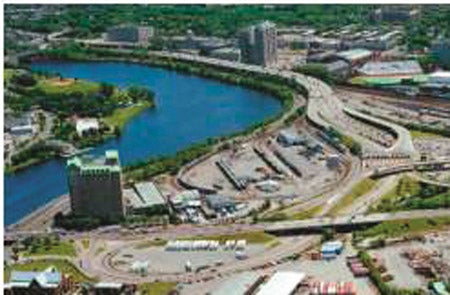

In 1997 Harvard University disclosed that from 1988 to 1994 it had purchased 52 acres of land in Allston, a section of the City of Boston. While some local residents and officials, including Boston Mayor Thomas Menino, criticized Harvard for buying the land surreptitiously through a property management company, the university said that the use of an intermediary is a common practice in real estate deals for large institutions or municipalities.

According to Kathy Spiegelman, Harvard’s associate vice president for planning and real estate, the university’s space needs necessitated the purchase of property, and Allston’s proximity to Cambridge and potential for development made it an ideal setting.

“The university began to understand that its history was a million to a million and a half square feet [of growth] a decade, and that therefore it wasn’t likely that the land holdings as they existed were going to be able to accommodate that,” she said. “Since most of the campus in Cambridge is surrounded by residential neighborhoods, and displacement of those neighborhoods was not in the university’s interests or in the realm of possibility, it was necessary to look to other places.”

And Harvard’s investment in Allston continues: The university recently bought property there owned by WGBH in Boston and purchased 48 acres from the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority in 2000. Harvard now owns a total of 248 acres of land in Allston, 108 of which the university does not currently use. Determining how Harvard will use the land will influence any additional purchases it may make in Allston, Spiegelman said. University holdings now include land occupied by retail shops, a supermarket, a former warehouse, a railroad yard, and the Genzyme biotechnology company. Some of the tenants have long-term leases that would likely forestall development in the near future, but not for the long term, said Spiegelman. “If we have some gradual planning processes, I don’t think any of these issues are going to ultimately stop the university,” she said. “The plan wasn’t purchases for now; it was purchases for the future.”

It may be 10 to 15 years or more before a fully realized Allston campus takes shape. The campus, planners say, would have to provide convenient transportation to Harvard Square, possibly by means of a trolley line. The university also must integrate its buildings into a residential middle-income neighborhood with a mix of industrial uses and businesses and long-term residents and renters.

Harvard should expect cooperation in the effort–as long as it communicates with and listens to the people of the neighborhood, says Boston City Councilor Brian Honan, who represents Allston and neighboring Brighton. Some resentment lingers over the manner in which Harvard bought the property, he said. Allston residents are concerned too that increased property values may drive current residents out of the neighborhood. Yet they expect that “Harvard will deal with us on an honest basis and will not try to put something in front of the community that they know will be objectionable,” he said.

“This is going to be the new gateway of the Allston/Brighton community, so you want something aesthetically pleasing, functional, and that won’t tie up the neighborhood in terms of density and traffic,” Honan said. “Harvard has shown a willingness to work with the community and build quality, first-class buildings.”

Such sentiments have not often been heard in Cambridge, which has frequently fought Harvard development, sometimes reasonably, sometimes not, say university officials. And while the possibility of moving the law school or any other university entity is driven first by academic needs, it is also driven by the concern that Cambridge will not allow the university to expand or redesign its buildings–such as the Gropius dormitories at HLS–for more practical use.

“We have been working very hard with the City of Cambridge to find ways for the university to grow within the boundaries of its campus in a way that respects our immediate neighbors. But the climate in Cambridge regarding growth is very difficult,” said Mary Power, Harvard’s senior director of community relations. “If the university can have confidence that it can grow to meet its academic needs within its Cambridge campus, then the necessity of moving elsewhere is less pronounced or less immediate. But what I’m hearing from neighbors is almost a mixed message. On the one hand they’re saying, ‘Don’t take the museums away. Don’t take the law school away.’ But they’re also saying, ‘You can’t grow. You can’t change.'”

Cambridge City Councilor David Maher, who chairs a newly formed city council committee on town-gown relations, said the city would not dismiss plans for Harvard Law School to grow on its current site. The city does not want to lose the law school, because of the prestige it brings and because it would likely be replaced with equally dense usage, he said. Also, Cambridge residents and officials would prefer managed growth of a law school to the establishment of science laboratories on the site. “I feel what we have to do is to find out a way that the universities can accomplish what they need to accomplish while not jeopardizing the integrity of our neighborhoods,” he said.

The city, Maher said, wants to be part of the process, a common refrain from people outside and inside the university. In addition to the law school and other graduate schools, Thompson and his university planning committee will hear from university scientists, many of whom also object to a move. They too fear the isolation and worry that science students and non-science majors would never intermingle. Yet if the law school moves instead, the university could not easily convert HLS buildings for the sciences, which among FAS departments is most in need of new space. It is hard, said Thompson, to envision Langdell as a wet lab.

His committee has given equal attention to the professional school and science center scenarios. After considering university and community viewpoints, and studying reports and models from consultants and planners, the committee will make a recommendation to Summers and the Corporation on what should move to Allston. Thompson said he expects his committee will make a recommendation in approximately two years.

Despite the objections from many quarters and the complications of the task, Thompson embraces the process. Harvard’s growth speaks to the health of the institution, he said. Indeed, the most successful universities have grown during the last century, said Thompson, and Harvard is fortunate that it now has space to expand. Yet with growth comes the burden of rallying disparate constituencies to support a move and showing that, if a professional school village were to grow in Allston, it would be in the interest of the law school as well as the university.

“We have to make sure this is going to serve the academic and educational interests of the university as a whole, and that means each of the schools will have to ultimately be convinced,” said Thompson. “If a move is to take place, not every faculty member or maybe not even the majority have to vote for it, but thoughtful faculty eventually have to come to believe that 50 years from now Harvard as a whole will be significantly better off as a result.

“What I am convinced of is if we do not now take advantage of the opportunity that Allston offers for developing an exciting new set of academic and cultural activities, our successors 50 years from now–including faculty sitting in the crowded law school–will say that we were shortsighted, that we lacked vision. They will rightly fault us for having left them with such a constricted set of opportunities for carrying on the educational mission of Harvard.”