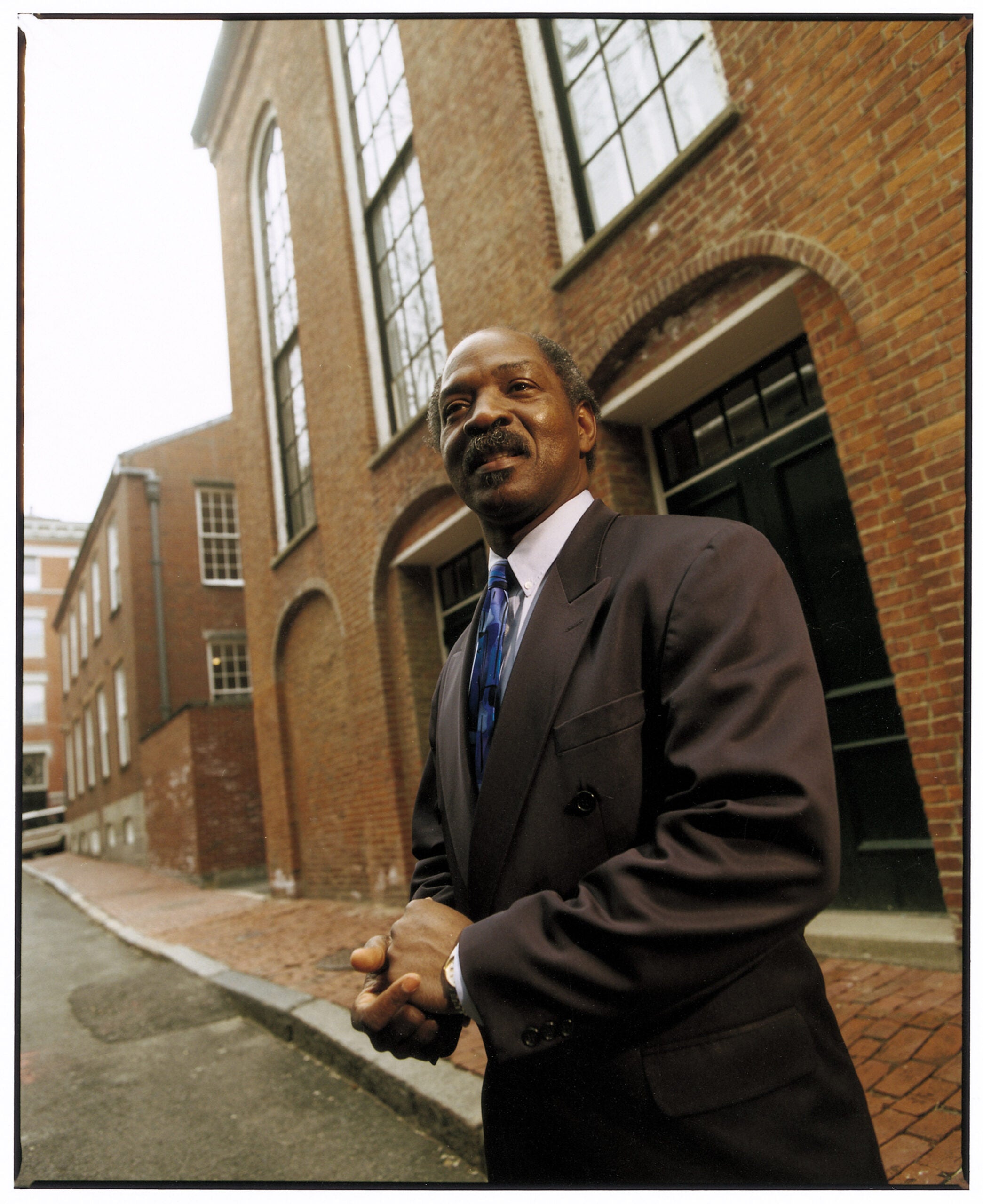

When Charles Ogletree Jr. ’78 was up for tenure at Harvard Law School, he served as legal counsel to Anita Hill during confirmation hearings of Clarence Thomas to the U.S. Supreme Court. Clearly Ogletree is not dissuaded by controversy, no more than were Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, or Justice Thurgood Marshall, whose likenesses adorn the walls of his Harvard Law School office. Now the HLS Jesse Climenko Professor of Law and head of the School’s Clinical Programs, Ogletree today champions a cause that ignites passion and unleashes bitterness, at the same time as it rides on hopes of racial healing.

The issue is slavery reparations. Its supporters argue that 246 years of slavery, 100 years of Jim Crow laws, and continuing discrimination have taken their toll on the African-American community. They point to pervasive disparities between African-Americans and other Americans in areas including health care, education, and employment. It’s a time when governments are apologizing and making amends for past wrongs–as the German, Austrian, and Swiss governments did for Jews who suffered at the hands of the Nazis, and as the U.S. government did with Japanese-Americans who were interned during World War II.

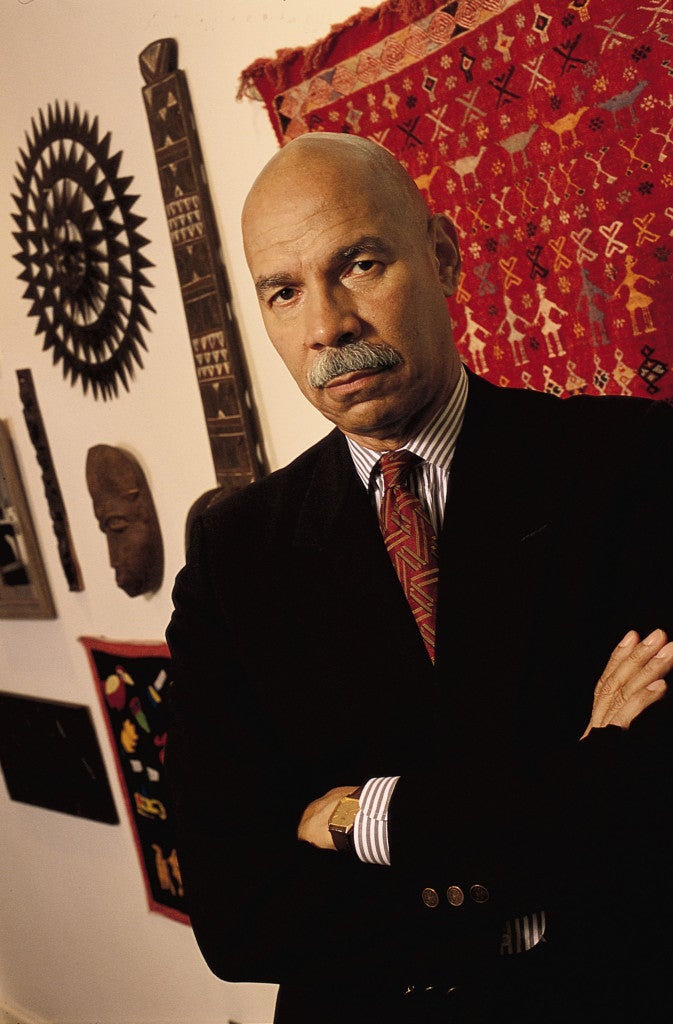

Ogletree and Randall Robinson ’70–an architect of the current reparations movement–have brought together a group of lawyers, academics, and activists to “do what we think has never been done before,” said Ogletree, “to try to engage in a comprehensive assessment of slavery, its impact on African-Americans, and whether or not there are any lingering bases for actual claims of restitution for slaves and descendants of slaves.”

The group is called the Reparations Coordinating Committee, and Ogletree said “an amazing series of possible actions” is slated for early next year.

Robinson, in his impassioned argument for reparations, The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks, calls slavery “a human rights crime without parallel in the modern world. For it produces its victims, ad infinitum, long after the active stage of the crime has ended.” He writes that, without reparations, “there is no chance that America can solve its racial problems–if solving these problems means, as I believe it must, closing the yawning economic gap between blacks and whites.”

Some critics–including other members of the HLS faculty–fear the reparations debate could in fact widen racial chasms among whites, blacks, and other minorities. Others question who should be paid–when no American slave is alive today to collect–and who should pay. At a time when so many Americans are the descendants of post-Emancipation immigrants, why penalize those who have no link to American slavery through deed or blood? Others dismiss the effort as impractical, foreseeing towering legal hurdles, such as the doctrine of sovereign immunity–which protects the federal government from damage suits, as it did from one of the early reparations cases against the Treasury Department in 1915.

The committee is considering a range of arguments and taking into account the many obstacles. Its investigation goes well beyond the borders of the United States, Ogletree says, noting it would be impossible to thoroughly examine American slavery without taking into account the role that African governments and individuals played. In August Ogletree will attend a UN conference in Durban, South Africa, on issues related to racism, racial discrimination, and xenophobia, and will participate in discussions of demands for reparations.

Ogletree does not underplay the importance of earlier attempts to remedy slavery and its effects, including the Civil War, the Reconstruction Amendments, civil rights legislation, affirmative action, and other government programs. These measures, he says, simply did not go far enough. He in fact compares the reparations suit to the landmark school desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education in importance but also in its strategy of drawing on experts to help shape claims.

The legal team, whose members are working pro bono, includes tort lawyers who have been involved in cases that led to billion-dollar settlements–among them a suit against the U.S. Department of Agriculture on behalf of black farmers. Criminal lawyer Johnnie Cochran is also part of the team. They are joined by activists–including the legal counsel for the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, representing thousands of members around the country–as well as academics.

U.S. Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.), who for the last 12 years has tried to create a federal commission to study slavery, is also on the committee. He is advising members on how legal action might further legislative solutions. As they prepare for the lawsuits, neither Ogletree nor Robinson loses sight of the fact that legal action, at best, has played an indirect role in past reparations settlements in this country. From the $1.5 billion to Japanese-Americans interned during the war to the $2 million to black survivors of the Rosewood, Fla., race riot, apology and settlement came years after failed lawsuits. At that time, as Ogletree put it, Congress had “the moral courage” to explore and address the wrongs, which then became known to a wider public.

Looking at slavery, Ogletree says, has drawn the committee into a complicated and personally agonizing examination of American history. Before any lawsuit is filed, the committee will hold public meetings this fall. Ogletree is particularly eager that the findings be shared with the American people. He says that working on these issues has been a life-altering experience.

“Very few of us have a clear sense of the actual tragic circumstances that led to the death and destruction of millions of Africans simply being transported from Africa to the United States,” he said. “It is in some sense every bit as tragic as the Holocaust, and yet it has received considerably less attention.” Moreover, Ogletree says that “there hasn’t been a decade when the chain of discrimination and bigotry and prejudice has been unbroken. And as much as you can talk about Jim Crow laws and de jure and de facto desegregation in the 19th century, you can talk about things like racial profiling, a discriminatory death penalty, and disparity in sentencing in the 21st century.”

* * *

Ogletree has the orator’s gift of holding on to the beginning of a long sentence until he reaches the end, as if the words were no more than a piece of string held tautly between two fingers. But his passionate eloquence when he speaks of wrongs to be righted is equaled only by his lawyerly reticence when asked about the particulars of the developing legal strategy. In fact, Ogletree seems wearied by the barrage of inquiries from national and international media.

Details are confidential, he says, but the committee has agreed on at least one core lawsuit (likely class action) against the federal government, with serious consideration of multiple suits. He did not reveal the identity of the defendants. Possible claims encompass issues as straightforward as access to educational opportunities and issues as broad and complicated as racial profiling and racial disparities in the criminal justice system. In addition, the committee is looking at private concerns that may have profited from slavery. Some companies, like Aetna Insurance, for example, have publicly acknowledged responsibility. More are likely to come forward as laws are passed, such as one in California, compelling companies to reveal such information. Harvard Law School itself is not free of this stain. Isaac Royall, who endowed the first chair in the law at Harvard, did so with lands he obtained by selling slaves he owned in Antigua. Ogletree says people are aghast when they hear such facts, but when it comes to the history of slavery in this country, it’s just the tip of the iceberg.

When Randall Robinson wrote The Debt, his peers told him it was a lunatic thing to do. They said that Robinson, who is head of the lobbying organization TransAfrica, would risk reputation and political capital. As it turns out, when the book came out last year, it became a best-seller, and he believes it helped convince a large majority of African-Americans to support reparations. But to succeed, he says, they need at least a minority of white support and sympathy. To that end, he has been attacking what he believes are misconceptions and misunderstandings about reparations.

According to Robinson, the core lawsuit will not target individuals. “No one is suggesting personal culpability. We are talking about crimes by governments against people,” crimes that should not be touched by statutes of limitations, because when governments commit such crimes, they “have a certain immortality.” The same is true for corporations, he says, bringing up a settlement with Volkswagen and other German manufacturers brokered by Stuart Eizenstat ’67 when he was undersecretary of state. Robinson says that although the people who ran the companies when they used Jews as slave laborers during World War II are long since dead, those in charge now accept responsibility for what happened over 50 years ago as a result of corporate policy.

Robinson believes relief should be need-based. “We are talking about salvaging people who have been intergenerationally bottom-stuck virtually since the Emancipation Proclamation.” Ogletree agrees and says that for people to expect that a reparations suit will get all African-Americans their “40 acres and a Lexus” is to trivialize slavery and its impact. “This is really about whether we can do something comprehensively to address the conditions that millions of African-Americans continue to face today,” he said.

In May remedies were still being discussed, and according to Robinson, members of the committee still disagreed. Some in the group favored cash payments to individuals, some land transfers (harkening back to the 40 acres first promised in 1864). Robinson says it all depends on how you define reparations. “Are you compensating people for an injury?” he asked. “If so, then you would have to go back and add up the unpaid wages. Let’s say we are talking about a trillion and a half. And you’d look at wage discrimination over the 20th century, several trillion. And you’d look at home equity discrimination, restrictive covenants, and redlining, and all of that. The figures suggest 80, 90 billion dollars per generation to the black community. You’d add up all the line items and then divide.” But Robinson said he wants to focus on “repairing the victim. That means emphasis on education and economic development. So whatever it costs in programs from birth to career age we spend to give people a decent chance to compete evenly in American society.”

Robinson doesn’t support cash transfers. The recipients, because of “the particular character of this victimization, would be the least able to hang on to the money. And then we would be in a position of having lost all rights to pursue this further. . . . I think it would be a major, major mistake.”

As a human rights activist, Robinson knows you can’t lay a calendar on how long it will take to convince Americans of the validity of reparations claims. Robinson waged a campaign of protest in the ’80s to heighten world consciousness about apartheid in South Africa (Ogletree was his attorney). In the ’90s he staged a 27-day hunger strike to protest U.S. policy toward Haiti and the treatment of Haitian refugees. “We do these things because they are the right and decent things to do,” he said. “With all the times I went to jail on these issues, I didn’t expect to see a free South Africa in my lifetime.” But change, he says, often comes more quickly than you’d expect.

According to Robinson, Americans should not be deterred by the massive amounts of money it would cost to set up the ambitious programs he envisions. “My God,” he said, “we ought to be compassionate, to care about people who’ve been damaged.” The real problem, he thinks, is denial.

“I’ve seen it in other countries. I’ve done human rights work for a long time, and I’ve seen other societies in denial. They just don’t want to talk about it. But we’ve been in a position to almost force them. . . . I think the spotlight will be on the United States to see how we behave when the shoe is on the other foot.”

* * *

Ogletree has heard from African-Americans who can trace their ancestry back to slaves and want to support him or be represented by him–although he says he is taking on no individual claims. He has received reasoned, respectful letters from those who adamantly disagree, inquiries from activists and academics who want to assist with the project, and threats that his friends and family wish he’d take more seriously. One letter writer said that African-Americans are not due even a “bucket of vomit.”

He seems saddened but not necessarily surprised by the acrimony. “We are mindful of the fact that even discussing reparations or slavery, or civil rights, or affirmative action, or criminal justice will lead to some bitter reactions and further recriminations from American citizens,” he said. “But when you attack a topic as controversial as this, you have to have the courage to stick with it.

“I am trying to reinitiate a conversation that was started around the time of the Emancipation Proclamation but that has remained largely unresolved in the 135 years since then. I feel obligated, I feel indebted, I feel committed to the voiceless slaves to say that in my lifetime I am not going to ignore this issue, just because it may create more enemies than I’d like to have, just because it may create just as much heat as light.”

Some question whether academics should venture into such troubled waters. But Ogletree is quick to point out that his work on this project, like on other projects, has not interfered with his academic responsibilities. As he enters his sabbatical, which begins in July, he says the year off will allow him to spend more time on the reparations work, but he also plans to complete a book on the legal profession and continue to work on a study of public defender systems in South Africa, China, and Israel.

Moreover, he objects to putting limits on the role of the scholar in academe. “We have to be guarded about our ability to suppress the efforts of faculty to engage in what many believe to be critical issues in legal and moral analysis. We’ve had great periods of challenge that Harvard faculty have been involved in,” he said, citing Watergate, debates over the Vietnam War, and most recently participation on all sides of the Bush/Gore election debate. “I think it is important that people who have the ability and the interest take on issues that may be uncomfortable but are necessary to be discussed.”

Many of his colleagues on the HLS faculty have expressed interest in reparations, although not necessarily agreement.

HLS Professor Christopher Edley ’78 says the principal benefit he sees to the debate is the possibility of educating Americans about the continuing legacy of slavery and Jim Crow. But he believes that “reparations is too divisive a banner under which to hold that discussion. It distracts from the relentless teaching that is needed to bridge racial divides.” Edley also faults the reparations arguments for not addressing the situation of other groups, such as Native Americans, Asians, and Latinos.

Finally, Edley, who was appointed special counsel to the president in 1995 and served on President Clinton’s race initiative, questions the feasibility of reparations. “As a political matter, this is so far from being achievable that it is a dangerous distraction from the concrete business of fixing our schools, defending civil rights protections, closing the opportunity gaps, and repairing the criminal justice system.

“What earthly evidence is there for the proposition that political majorities will support an innovative theory of generational indebtedness and guilt? We’ve got a better chance of persuading them that every child, regardless of class or color, deserves a world-class education. That is the battle. That is the battle these great black minds ought to be focused on.”

* * *

To Ogletree, the word reparations means healing, repair, restoration. But before you can get to healing, he believes, you have to tell the story of what’s been lost: millions of individuals who don’t have a name. Slaves tossed off ships to lighten the load, sold at auction block, buried in markerless fields, deprived of their language and culture–their sense of love and community taken away. Ogletree has tried to trace his own family back, and at a point it just stops. “There are no grave markers, no birth records. Just a void that is palpable,” he said. “If I could take the step to fill that void, to me that would be important. There would be no anger. There would just be a sense of closure.”