HLS professor seeks to make copyrighted works accessible to students with disabilities

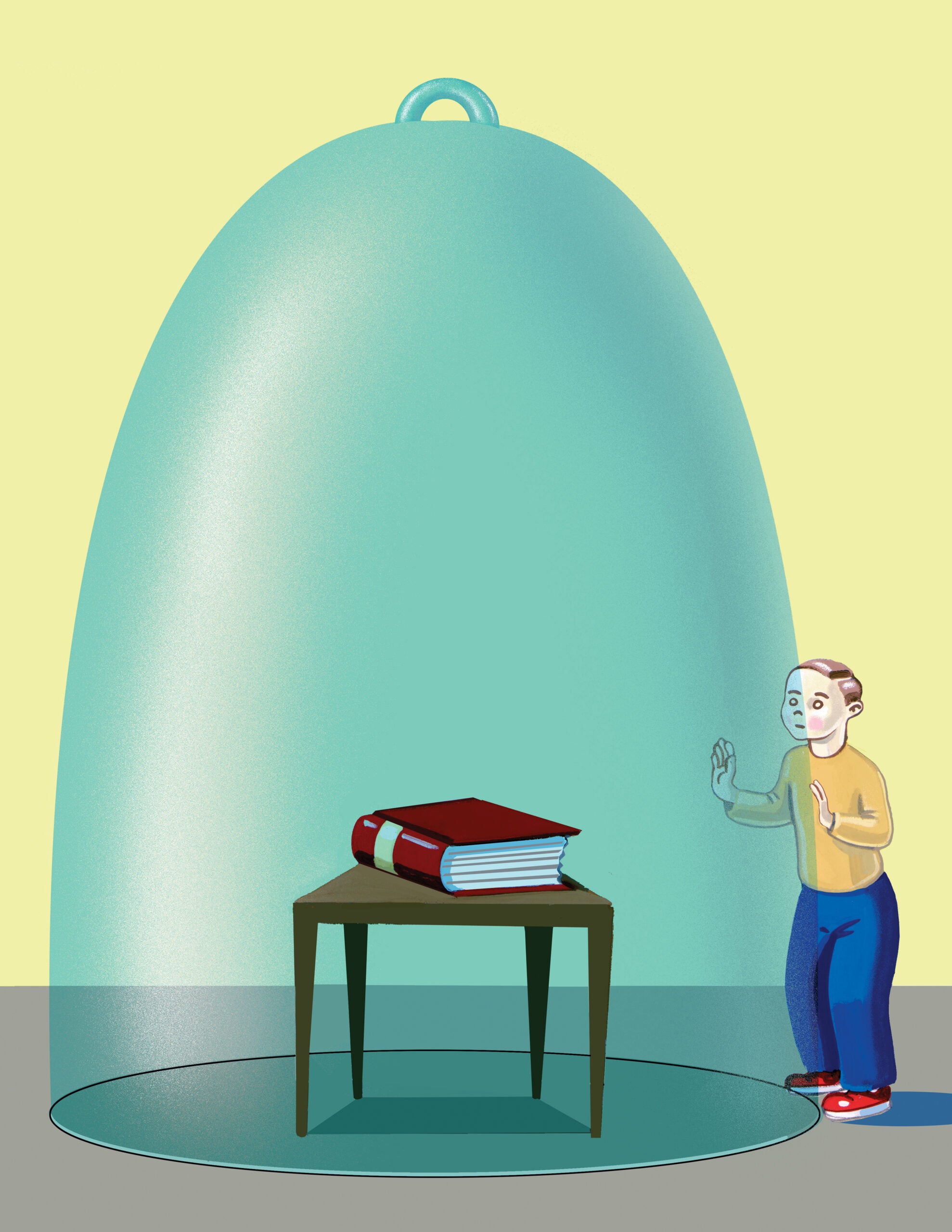

Even if a child cannot hold a textbook or see the words on its pages, the law says she must still have access to the same education as her classmates. The good news, says Professor Martha Minow, is that once a book has been digitized, the technology exists to open up the curriculum to children with a wide range of disabilities. The challenge, she says, is that “every opening up of the text leads to a copyright violation.”

Four years ago, with an organization called the Center for Applied Special Technology, Minow began working on a Department of Education project to implement the 1997 amendment to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. While it was Minow’s knowledge of special education law that brought her to the collaboration, she soon realized that copyright was where she needed to focus.

Particularly pivotal was the Chafee Amendment, which allows for materials to be scanned or copied for persons with visual or related impairments. Some have assumed that this exception could be expanded to cover those with other disabilities, but so far the courts have been silent on this issue. Minow soon became convinced that, beyond looking into legal strategies to fend off lawsuits, the project should work directly with the textbook publishers. She turned to her colleagues at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society, who have been grappling with copyright issues affecting the film and music industries. In October 2002, the center co-hosted a meeting that brought together for the first time the major textbook publishers with technology and copyright experts.

The publishers were wary at first, says Minow. But quickly most everyone agreed that current efforts–including teachers copying and scanning books–barely serve the visually impaired students who are covered by the Chafee Amendment, let alone students with other disabilities.

Most also agreed they must find ways to get children access to the curriculum without depriving publishers of control over the quality or content of their products. And, of course, they had to make sure that publishers could still make a profit. Erica Perl, managing director and research attorney at the project, says one of the challenges involves the cost of negotiating digital rights with numerous artists and writers. But if publishers were to provide digital versions of all texts at the beginning, she says, money now spent on converting the textbooks might be used for these contracts.

With help from the Berkman Center and its Digital Media Project, Minow, Perl and HLS students are trying to come up with just this sort of business model innovation. “We’re trying to sweeten the pot,” says 1L Charlie Hoffmann, a former high school teacher and software engineer. “We have to figure out ways to incentivize publishers to do this for their own gain.” Many publishers already use traditional accounting systems, which rely on schools buying a book for every student who wants an electronic version. But the project is also exploring alternative compensation schemes for the K-12 textbook market, just as Professor William Fisher III ’82 has done for the music industry (see Up on Downloading). According to Minow, there are parallels between the problems faced by the two industries, but there are also major differences, such as the nature of the demand. “There is no tremendous desire for bootlegged copies of sixth-grade math texts,” she says. And the number of K-12 students considered disabled under IDEA (less than 9 percent) is just a grace note compared to the market for a Norah Jones CD.

Yet, the way Minow and her partners at CAST are thinking about education, the pool of users could get bigger. Minow says studies show that many nondisabled students have different learning styles and that they would benefit from much of the educational software that expands print textbooks. “In addition to working within the existing law,” she says, “we are trying to envision a world in which we don’t create two sets of teaching materials but actually have the fully accessible curriculum for every kid.”

Minow says working on the project has been exciting and emboldening. Seeing a child who has attention deficits engaged by interactive versions of the lessons, or another who can’t speak presenting a multimedia report that suddenly makes him the cool kid, gives her hope for making the promise of the 1997 special education law the reality.

3L Deborah Gordon agrees, calling her three years on the project the best part of law school. It took her into the Boston Public Schools with Perl to study how technology is already at work. It also led them to investigate the laws in each state regarding the digital versions of texts that publishers have to provide. Encouraged by that study, Congress authorized a national panel–on which Minow has served–to generate a standardized file format for digitized versions of all texts. The proposal has now been incorporated into the latest version of the special education law that’s pending before the House and could lead to the establishment of a national clearinghouse of digital files. Someday Gordon hopes to work in education law, and she is grateful that she got “to meet people and talk to them about the issues instead of just reading about them in the classroom.”

Minow says the project has been educational for her too: “It’s provided a terrific window for me into how lawyers can become problem solvers.” From business plans to agreements, she says, “We’ll use whatever tools it takes to solve the problem.”