The word leaps off the page. It is unmistakable, unavoidable. Nigger.

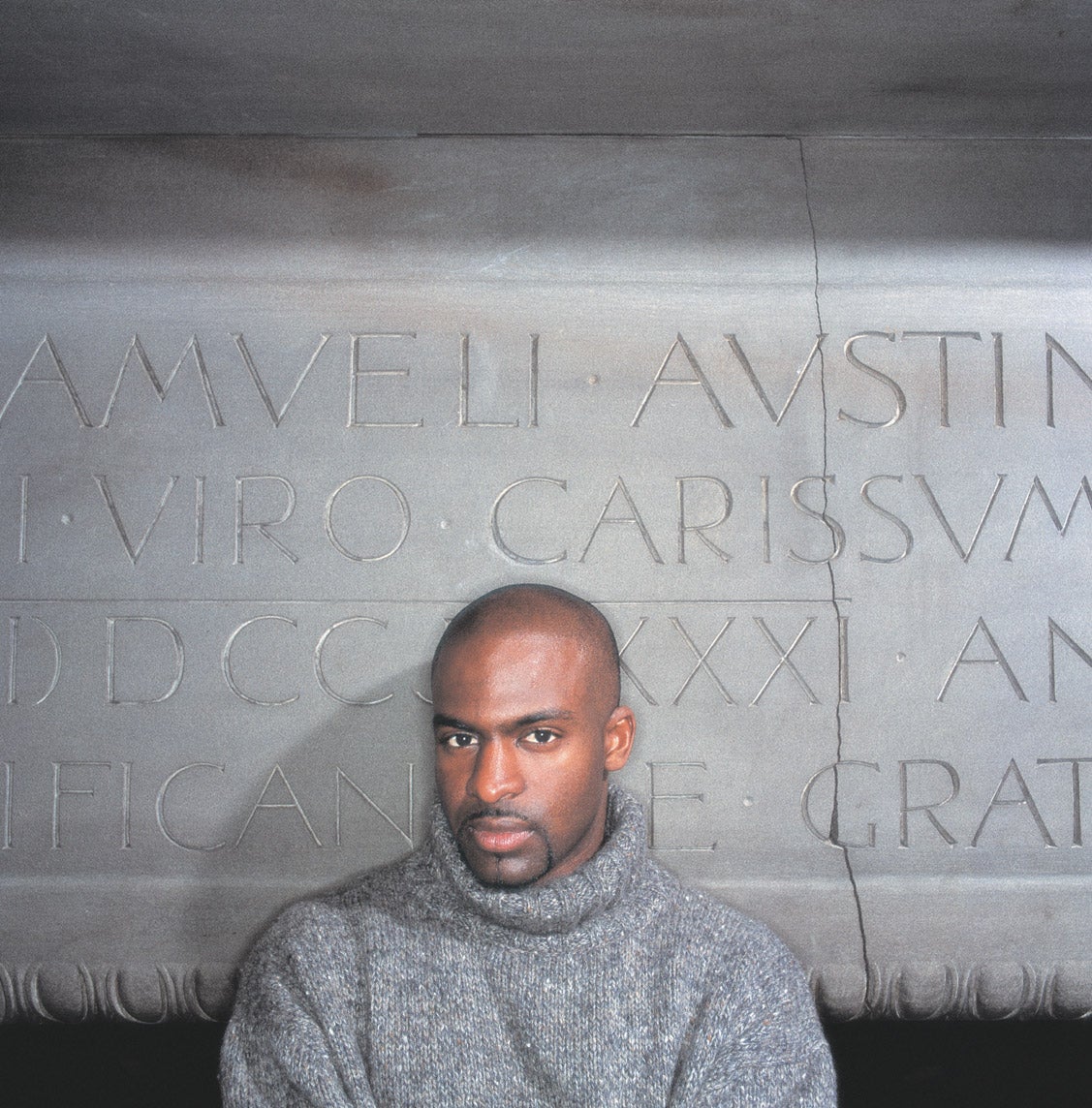

In Bryonn Bain’s view, the word still resonates in the heart and soul of the institutional powers in America. The word and all it conveys became manifest after he was arrested in his native New York City and held overnight for a crime he didn’t commit. For the crime, he says, of being a black man, of being, in the eyes of those in power, a nigger.

Bain wrote about the experience last year as a second-year HLS student for Professor Lani Guinier’s class Critical Perspectives on the Law. In his essay, he weaves the story of his arrest with “a special Bill of Rights for non-white people in the United States—one that applies with particular severity to Black men.” Bain’s first amendment: “Congress can make no law altering the established fact that a Black man is a nigger.” Each subsequent amendment invokes the same hateful epithet and captures how many people still perceive African Americans, according to Bain.

“Much of white society still feels that way, and it’s embedded in American institutions,” he said.

After Guinier urged him to seek a wider audience, Bain sent the essay to the Village Voice, which published it as a cover story in late April. Over 40,000 people have responded to the article, many with praise, some with anger, catapulting Bain to the forefront of a debate on race and justice.

“A lot of people want to deny the state of the black community and that these incidents are occurring pervasively across the country,” said Bain.

In the story, called “Walking While Black,” Bain writes about witnessing a group of men flinging bottles at an apartment window during an argument. As he, his brother, and his cousin head to the subway, several bouncers from a nearby club stop them and call the police. “A crime had been committed, and someone Black was going to be apprehended—whether the Black person was a crack addict, a corrections officer, a preacher, a professional entertainer of white people, or a student at a prestigious law school,” Bain wrote.

What followed, he wrote, was a night in a filthy cell and contempt from police officers, further exacerbated when they found out Bain attended Harvard Law School.

“Once I told them I went to law school, it made it worse,” said Bain. “They picked at us a lot more because of it. That’s part of the irony about having these opportunities. You’re often being challenged because people don’t think you deserve what you’ve got.”

In February, four months after the incident, the charges were dropped. But Bain’s story has reverberated beyond the classroom at HLS and the streets of New York City. A camera crew from 60 Minutes trailed Bain all summer in preparation for a segment scheduled to air in November. He has received mail from across the country and internationally, with people relating their own experiences, and some turning to him for answers to improve conditions for minorities.

Bain welcomes their call to action. The “privilege and access” he enjoys as an HLS student empower him to champion social justice and foment change in society, he says. With Guinier’s assistance, he has organized a team of a dozen young black activists to write a book that draws on the premise of the Voice article, with each amendment becoming a chapter reflecting the black experience in America.

A musician and poet, Bain has also added a discussion link about his story to www.blackoutartscollective.com, the Web site for his nonprofit organization, which conducts youth arts programs “to encourage young people of color to value creativity, collective work, and cooperation, and empower them with the understanding of the African, Asian, Latino, and Native American peoples.” Bain said he intends to remain in the arts and continue his community activism when he completes his J.D. degree. He will not risk his independence, he says, by joining an organization that may squelch his social conscience.

“I must be free to speak my mind about what’s happening, to say the truth as I see it,” he said. “I have no interest in working at a corporate law firm at this point in my life. I don’t want to work in any environment in which people are afraid to speak the truth.”

He is considering pursuing legal action against the New York City Police Department and the club whose bouncers detained him. At the same time, he emphasizes that “I have a cause, not a complaint.” Bain wants his story of being “abducted, degraded, pushed around, and publicly humiliated” to lead to public discourse and public action. Only then, he believes, will the message behind his own Bill of Rights be ratified.