Jeff Kichaben ’80 was on top of the world. Then his mother called. She had just read a flattering newspaper feature that highlighted his ability to help parties resolve disputes outside of court in his Los Angeles practice. It was a wonderful article, she said. But she had one question. “Are you still really a lawyer?”

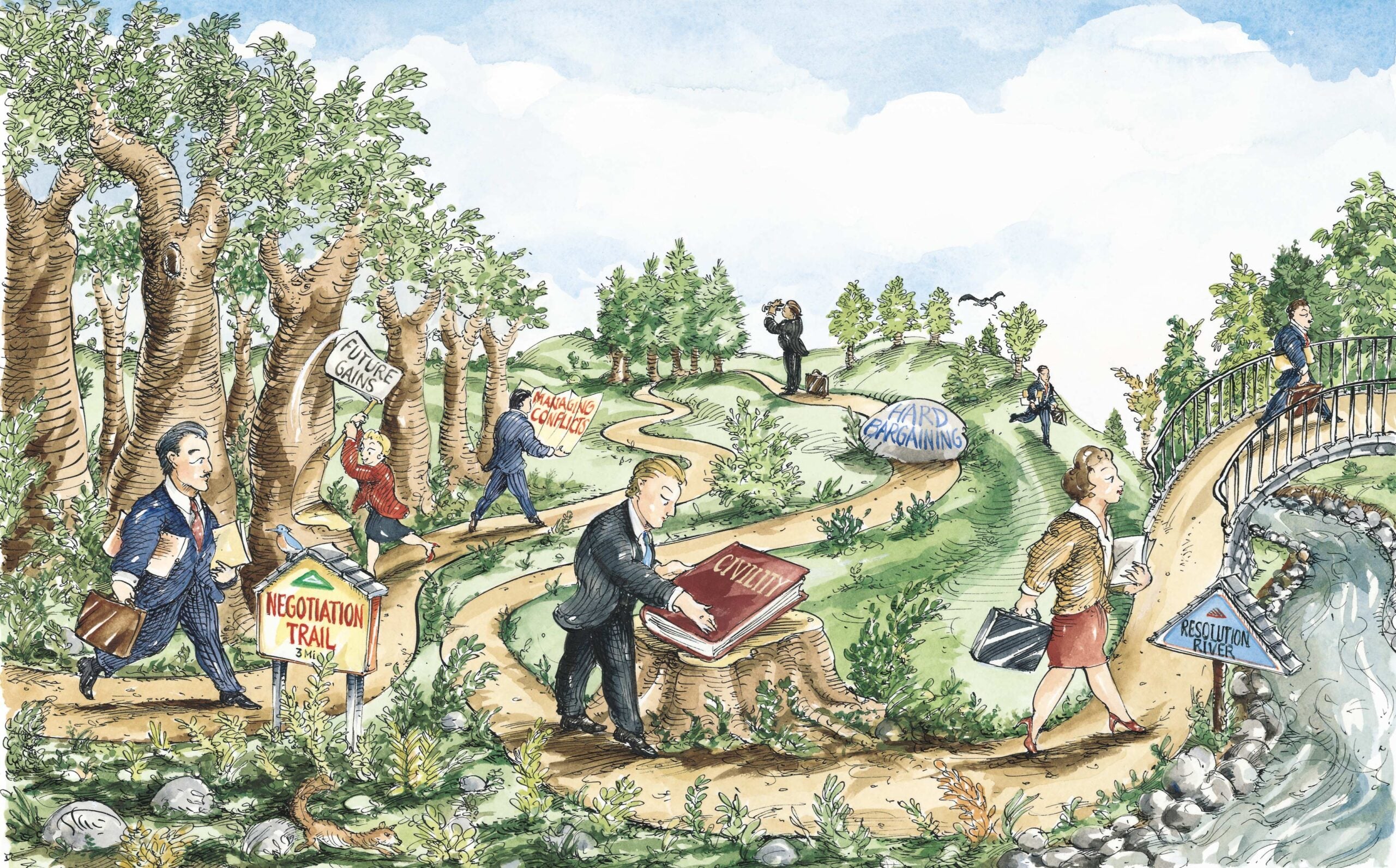

That depends on one’s definition of lawyer. Robert Mnookin ’68, Williston Professor of Law and chairman of the Program on Negotiation (PON) at HLS, contends that a lawyer should facilitate cooperation and understanding, and serve as a force for agreement and even reconciliation. In his new book, Beyond Winning: Negotiating to Create Value in Deals and Disputes (cowritten with Scott Peppet ’96 and Andrew Tulumello ’96, who both worked at PON), Mnookin encourages lawyers to move beyond a reflexive adversarial posture to a problem-solving stance.

“As negotiators, lawyers have what Abraham Lincoln described as a ‘superior opportunity to do good’ and yet they also have the capacity to do considerable harm, said Mnookin. “Sometimes egged on by the client, ineffective negotiators often mindlessly employ hard-bargaining tactics with disastrous results—relationships are jeopardized, potentially productive deals are killed, and conflicts that might be resolved through negotiation instead result in protracted, scorched-earth litigation. Our book seeks to expose the tensions that make legal negotiations especially challenging, and to offer lawyers practical, tough-minded advice aimed at turning disputes into deals, and deals into better deals.

In his book, Mnookin outlines strategies for the modern breed of lawyers who still face old-fashioned dilemmas. “This book is not about a utopia that does not exist but is instead grounded in the realities of an adversarial system, where many clients and lawyers alike see negotiation as a zero-sum game.

Mnookin’s teaching and writing draw on insights from economics, social psychology, cognitive sciences, and game-theory. But his own “real-world experience has also influenced his theories on negotiation and dispute resolution. Perhaps his most publicized case arose in the late-1980s, and involved the conflict between the two largest computer companies in the world at the time, when IBM claimed Fujitsu had copied its mainframe operating system. Mnookin and his coarbitrator worked with parties to shape a “secured facility regime that protected IBM’s intellectual property while giving Fujitsu, for a substantial fee, the right to use specific information from IBM programs in its independent software development activities. More recently, Mnookin was credited with transforming the way the trustees, musicians, and management of the San Francisco Symphony negotiated a six-year collective bargaining agreement.

“Experiences like these have taught me two important lessons, said Mnookin. “First, even in situations of intense conflict, there are nearly always opportunities to create value. And second, that lawyers can sometimes play a role as a ‘process architect.’ A lawyer can do more than simply help resolve a single dispute; lawyers can help develop systems and procedures that allow parties who do business together to work out their differences over time in a wide range of areas.

Mnookin acknowledges the barriers that can hinder a value-creating negotiation. In his book, he outlines the tensions inherent in the process, and strategies for managing them. Predominant among them, he said, “is the tension between opportunities to make the pie bigger, to create value in a variety of ways, and the inevitable necessity of dividing the pie.

Sometimes, even in dividing the pie, a lawyer can propose a novel solution that in the end benefits both sides. John Wofford ’62, who operates his own mediation practice in Cambridge, Mass., after working in government and real estate law, was called in to mediate a dispute that had lasted over two years. A contractor and subcontractor were mired in a lawsuit over a large project in Massachusetts, with three major components to the litigation, millions of dollars at stake, and thousands of pages of depositions, motions, and briefs. After having long, separate meetings with both sides—including each CEO and his lawyers—and reviewing their briefs, Wofford estimated that if litigation continued, each side was most likely to be awarded about the same amount of a very large pie. So he proposed something that dumbfounded the lawyers on both sides. Forget about the whole thing, Wofford suggested. He asked the CEOs to meet alone and talk about it. Fifteen minutes later, they dropped the lawsuit. “The clients had continuing relationships with businesses that were dealing with each other, said Wofford. “They had every reason to try to resolve things, so they decided to resolve it as a draw.

The lawyers were paid well even though they didn’t directly resolve the dispute. But they did not receive the additional hundreds of thousands of dollars that each side estimated as its future legal costs had the case not settled at mediation. The fee structure, Mnookin notes, can serve as a disincentive for lawyers to strive for a quick solution to a case, part of what he calls the tension between principals and agents. Various fee structures, from contingency, to hourly, to fixed, may cause suspicion of the clients’ or the attorneys’ actions. Mnookin advises the parties to acknowledge the tension, not avoid it, and such candor will build trust. Both the lawyer and client can then work toward a common goal in the most efficient manner.

“Sometimes the self-interest of the lawyers gets in the way of seeing the value of an early resolution, said Wofford, “but I think most really good lawyers understand that in fully representing their client, they owe it to the client to explore all possibilities.

Lawyers Lead the Way

Problem-solving attorneys do not always face their philosophical brethren in negotiations. Instead, as Mnookin outlines in his book, some lawyers rely on “hard-bargaining tactics, such as threats, personal insults, bluffs, and belittlement, which impede productive negotiation, he says.

Some lawyers simply don’t know any other way, said Elliot Surkin ’67, chairman of the real estate department at Hill & Barlow in Boston. Surkin, who has negotiated many complex development deals, said that many lawyers “just want to beat up the other side and win.

“I have seen a lot of situations where people have been very tough and through the force of their personality, they achieve what they consider to be very desirable results, he said. “I have often seen that translate itself over the years into a loss because they have won too much and they have achieved an agreement that is not right. These long-term relationships don’t work out correctly because they didn’t produce a fairer result in the beginning.

“I have seen a lot of situations where people have been very tough and through the force of their personality, they achieve what they consider to be very desirable results. I have often seen that translate itself over the years into a loss.”

Elliot Surkin ‘67

Lawyers who trust one another will find fewer impediments to achieving value in negotiation, Mnookin says. But lawyers often don’t have continuing working relationships, he said, and often don’t know the style of the person on the other side of the table. The result, said Mnookin, is that some lawyers become “switch hitters, changing their approach in reaction to the style of opposing counsel. But lawyers should not cede their strategy to the other side, Mnookin advises.

“One of the themes of the book is that in dealing with the lawyer on the other side, someone who knows what she is all about and knows what her orientation is can often influence the behavior of the opposing lawyer, said Mnookin.

Mnookin urges lawyers to lead the way by negotiating a problem-solving process—and a collaborative working relationship—before negotiating a settlement. A lawyer should enter a negotiation seeking “value-creating trades and framing that search as an essential part of serving your client.

As an example, Mnookin writes about a divorce case, with an attorney adhering to a problem-solving approach. The attorney starts by acknowledging the “typical approach to a negotiation: the attorney for each client proposing an extremely one-sided agreement, then days of haggling and posturing, and a possible settlement after much vitriol.

Instead, the divorce lawyer suggests that both attorneys talk so that they can understand each side’s interests and concerns, and draft a variety of options that might serve those interests. The attorney thus demonstrates a commitment to his client, but also a willingness to work with the other side to create an efficient and fair result, according to Mnookin.

The other attorney may still refuse to accept this process; some lawyers, Mnookin writes, like to play hardball. In dealing with such an adversary, problem-solving lawyers needn’t stray from their approach, Mnookin contends. “Almost anything a hard bargainer says, he writes, “can be reframed or restated as an interest, an option, or a suggestion about a norm that might be used to resolve distributive issues.

When faced with an unyielding attorney, Mnookin also recommends changing the players in the negotiation. This may involve bringing in a mediator trained in dispute resolution. In some cases, says Marjorie Corman Aaron ’81, former executive director of PON who now teaches negotiation and alternative dispute resolution at the University of Cincinnati College of Law, a mediator may change the way a lawyer approaches negotiation.

Aaron said that lawyers whose styles clash—typically one who makes extreme claims versus another with more realistic requests—often can’t resolve their case. But the negotiating style of these same lawyers can change in a mediation, she said.

“They figure out that they need to play in a different way, that they need to say things in a certain way that is not calculated to make the other side storm out, that is not further poisoning the feelings toward one another, said Aaron. “I think that lawyers who have participated in a number of mediations have figured that out.

She has seen it in her own work as a mediator, observing and molding the evolution of one lawyer with whom she has had five mediations. “He had the reputation as a tough guy, and we had a very successful mediation the first time we did it, and he actually asked me for feedback, and he is now very different. And when I say that, it does not mean he’s not a zealous advocate, that he’s a pushover. He is not. But he is definitely more skilled.

Clients and Other Hurdles

Sometimes the first problem that lawyers have to solve lies within their own clients.

Every actor enters a legal negotiation with societal expectations, including the client, Mnookin notes. “The book talks about the kinds of things that can be done to establish the right sorts of relationships with clients to support problem solving, he said. “Often [clients] have what I call the zero-sum mindset: Whatever I win you lose. Or they have kind of the hired gun mindset, that the lawyer’s job is simply to shoot at the other side. You have to be able to talk to clients about these expectations because often the client will come in wanting to fight a war.

Lawyers, Mnookin writes, should help clients understand their interest and priorities. Lawyers should help clients understand their “informed choice, the ability to see the costs and consequences of different approaches to solving their problem. And lawyers should always respect their clients, but they should also respect themselves.

Part of the challenge is weighing the client’s realistic opportunities and risks. A problem-solving lawyer, Mnookin writes, should not manipulate a client’s expectations.

Yet sometimes clients’ expectations simply do not match the facts of the case. Jeff Kichaven, who now operates his own mediation practice in Los Angeles after serving as a partner in a law firm, helped a lawyer bring his client back to reality in one dispute involving contractors and insurance companies. The case “was like a Greek tragedy, Kichaven said. Everyone knew it should settle, and everyone knew the price at which it should settle, he said. Yet one client was convinced that his passion and commitment to his cause would lead to victory.

“The lawyer had given me some signals that I really had to lower the boom on his client. The lawyer wanted me to do that because the lawyer felt very strongly that it was in the client’s best interest and that the client did not really apprehend and appreciate all the risks of litigation, Kichaven said. “I remember putting both my hands on this guy’s two shoulders and looking him in the eye and saying, ‘I know how deeply you feel about this case and the principle, and you don’t want to be taken advantage of. Let me tell you, the way the United States legal system works, the sincerity of your belief is not the only thing that is taken into account. The legal system looks very heavily at documents and financial records and relies on that just as much. Although you are sincere, the other side is sincere too, and they have all this documentation and I can see the look in your lawyer’s eyes’—and I made sure that the lawyer was standing right there because if he didn’t like what I was saying, I wanted him to stop me at any time. I said, ‘If you were my own brother I would be giving you this same advice. Take the money and run.’

Clients often bring intense emotions to a case, Mnookin writes. Problem-solving attorneys should not avoid the personal and emotional dimensions that affect a negotiation, he contends.

Wofford recently mediated a real estate dispute between two branches of one extended family that co-owned a triple-decker home. But it wasn’t just a dispute over the house. Because the lawyers on both sides understood and acknowledged the emotions enmeshed in the case, they were able to lead their clients to a successful resolution, said Wofford.

“Those lawyers were very helpful acknowledging the huge hurt that this family was feeling, but also getting the clients to move away from that feeling of ‘I want to kill these people,’ he said. The lawyers, Wofford added, devised a buyout and rent structure to provide an incentive for one feuding branch of the family to move out. “These lawyers were also very creative in developing new options.

While Mnookin says “negotiations behind the table are every bit as important as those across the table, he also highlights other factors that can complicate and muddle the negotiation process. Many negotiations involve more than a lawyer and client negotiating with another lawyer and client. In real estate development projects, for example, Surkin works with government agencies, politicians, neighborhood groups, and corporations. The more people and disparate interests involved, the more difficult it is to forge agreement, he says.

“I think everybody knows now that it is easy to make a mess and to hold things up, and they are willing to risk various things to do that, which often seems an abuse of the process, but it becomes one of the negotiating forces, Surkin said.

Some big deals simply cannot be accomplished because of the many constituencies involved, according to Surkin. Yet he has also seen deals improved by input from different interested parties. Most important for an attorney, he says, is to learn the perceptions of all sides, and then ask all sides to be open to a solution.

“You’d say to each side: ‘You have to pledge yourself to remain flexible to listening to

the other side, and not simply to be sitting here to maximize your own interest. If you can’t really honestly pledge that, then we won’t have a negotiation, we will have a war.’ And one side will win the war, but it won’t produce the most positive result. It might produce a kind of stupider result than you could get if everybody could control themselves and remain flexible, said Surkin.

Getting to Beyond Winning

Mnookin’s book and teachings are grounded in a program that brought HLS to the forefront of the study of negotiation. Professor Emeritus Roger Fisher ’48, coauthor of the best-seller Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In, first taught the Negotiation Workshop at the School in 1979, the same year he founded the Harvard Negotiation Project. At the same time, Professor Frank Sander ’52 developed the School’s first course on alternative dispute resolution. The Program on Negotiation, which was inaugurated in the early 1980s, includes a consortium of faculty from schools throughout the area, and emphasizes research, academic courses, and professional training.

Mnookin came to HLS from Stanford to extend their work and lead the program. “The special opportunity I saw here—and this book represents the effort—was to really focus on the special dilemmas and roles of the lawyer as negotiator, Mnookin said.

“In the world of business and financial negotiations that I spent so many years in, so-called cooperative bargaining was not the way things got done.”

James Freund

In his book, Mnookin seeks to bridge what some see as the gap between academic theories and actual experience in negotiation. James Freund ’62, author of Smart Negotiating: How to Make Good Deals in the Real World, questions the practical application of academic theories on negotiation. He says that seeking fairness out of a negotiation and trying to move beyond distributive issues are commendable ideals. But those ideals seldom meshed with his experience as a mergers and acquisitions lawyer at Skadden Arps in New York City, where he practiced prior to his recent retirement.

“In the world of business and financial negotiations that I spent so many years in, so-called cooperative bargaining was not the way things got done, said Freund. “The approach to negotiation exemplified by Getting to Yes contains much that’s of real value, and it would be gratifying if everyone sat around a table and worked together to solve all problems. But it just doesn’t happen that often in the rough-and-tumble business world. And if you walk into a commercial negotiation for a client trying to pull that off, you can really get blindsided.

Although Freund frowns equally upon the threatening coercive approach of some competitive negotiators, he recognizes the necessity of mastering the tactics of everyday positional bargaining. For example, he said, if the buyer on the other side presents a lowball offer for your client’s business, you ought to react by disparaging the offer. “If you want to get the buyer up into your zone, you have to make him realize that he’s far off the mark, said Freund. “Otherwise, he may think you’re not really dissatisfied, and will be inclined to hang tough rather than get realistic.

On the issue of focusing on real interests, Freund said most denizens of the business world focus solely on monetary matters. “If a guy is asking a million dollars for his property and you’re trying to find out his real interest, most often his real interest is that he’ll take $900,000. It’s because that’s how the game is played, that’s how they measure success.

Freund praises Mnookin, however, for his practical perspective shaped by real-world experience. Mnookin doesn’t discount the barriers that problem-solving attorneys face. He acknowledges that “some lawyers will find this orientation appealing and congenial, while others will not. His book, he believes, will speak to all of them, and help make them better attorneys. And his mission—to unlock the cultural shackles that bind lawyers and squelch opportunities—is gaining adherents throughout the profession. Kichaven, for one, sees HLS and the Program on Negotiation as the epicenter of a movement that has improved legal advocacy for all. After meeting Fisher, Sander, and Mnookin last year at an ABA seminar on alternative dispute resolution, he saw it more clearly than ever.

“Being exposed in a more detailed, in-depth way to the work of the Program on Negotiation and Mnookin and his brothers and sisters on the faculty, really made me feel that I was doing exactly the kind of work that graduates of Harvard Law School ought to be willing to take the risk to do, really changing the way law is practiced in our country, he said.