Rest assured, Dean Blackwood ’95 is not demanding a 45-foot trailer filled with cardamom incense sticks and candy bowls with all the green M&M’s removed. In an industry with its share of divas and dilettantes, Blackwood is down-to-earth and down home, a Texas boy with a great job and a great sideline that just happens to have recently placed him among stars like Bruce Springsteen and Norah Jones and Johnny Cash. You could call him Grammy Award-winning Dean Blackwood, but he’d probably rather you call him a music nerd showcasing musicians who deserve more exposure than they’ve gotten.

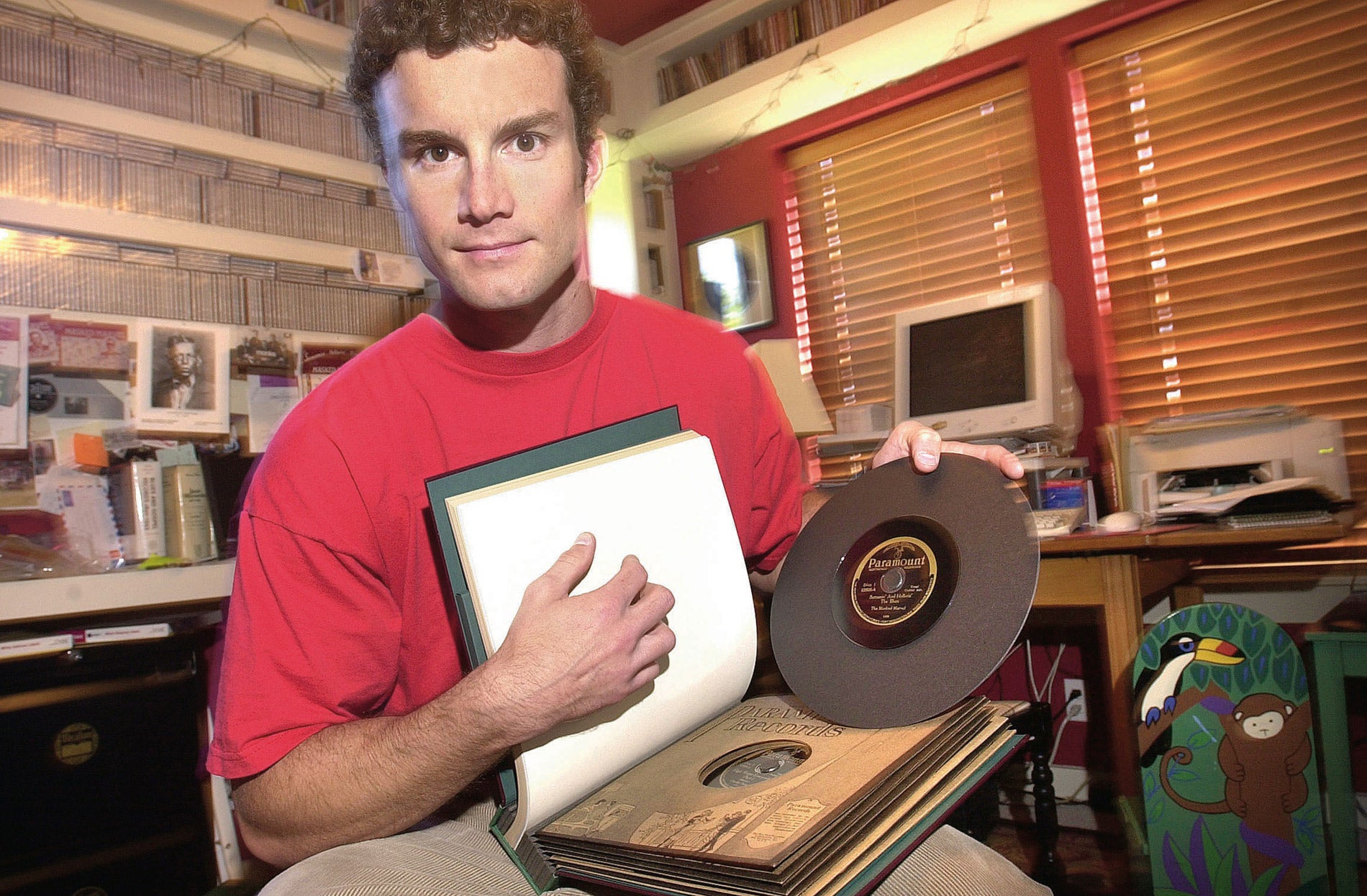

Blackwood runs Revenant Records, whose recent project, “Screamin’ and Hollerin’ the Blues: The Worlds of Charley Patton,” snagged awards for best boxed or special limited edition package, best album notes and best historical album at this year’s Grammys. The company (www.revenantrecords.com) produces and lovingly packages “raw musics,” which Blackwood describes as “the work of great, uncompromising artists, undiluted by commercial meddling.”

That’s what he’s listened to since he was a kid, the type of kid, he says, who made music–“weirdo” music at that–his primary entertainment instead of background ambience. “I’m obsessed with all sorts of music, including stuff that may appear on the mainstream radar,” said Blackwood. “It’s just that these seem to be particularly egregious examples of people who hadn’t been given the appropriate treatment. Neglected gems-that’s what we focus on as a label.”

The music obsessive evolved into the record executive while Blackwood was at HLS. At that time, he met John Fahey, an eccentric music savant who had inherited some money and wanted Blackwood to use it to run a record label. Since its inaugural release in early 1997, the company has produced only 16 records, but the quality inspired GQ magazine to call it “the best record label in the world.”

The world’s best label is run out of perhaps the world’s smallest record company headquarters: a corner of a bedroom in Blackwood’s Austin, Texas, home, staffed by the company’s only employee, his wife, Laurie. Despite the Grammy attention, Blackwood doesn’t plan to make the company bigger. His job as an in-house attorney with Dell Computer Corp. pays the bills; if he had to rely on Revenant’s sales to support his family, it might not be the same record label with the same high standards, he says.

It’s not that he has an aversion to success, an “indier than thou” attitude prevalent among purists, Blackwood says. He’d like everyone to have a Charley Patton or Captain Beefheart or Dock Boggs record. “We don’t want to be a bunch of eggheads about it and make it dauntingly academic,” he said. “We try to make it fun and great to look at but also have enough depth of scholarship and attention to detail that the real hard-core folks will want to have it as well.” You don’t have to be a music freak to appreciate Revenant’s music, Blackwood says. He will obsess so you don’t have to.