Robert McDuff ’80 remembers clearly what first got him thinking about civil rights and the profession of law. In 1968, when he was 12, he read a newspaper account of a murder trial in his hometown of Hattiesburg, Miss. The victim was Vernon Dahmer—an African-American shopkeeper and civil rights leader who let other African-Americans use his store as a place to pay their poll taxes. Dahmer had been killed by members of the Ku Klux Klan in 1966, his house firebombed during the night. As McDuff read the article, he found himself wondering: “Why did they kill this man? What are these lawyers doing? What does it mean to be a lawyer in a courtroom?”

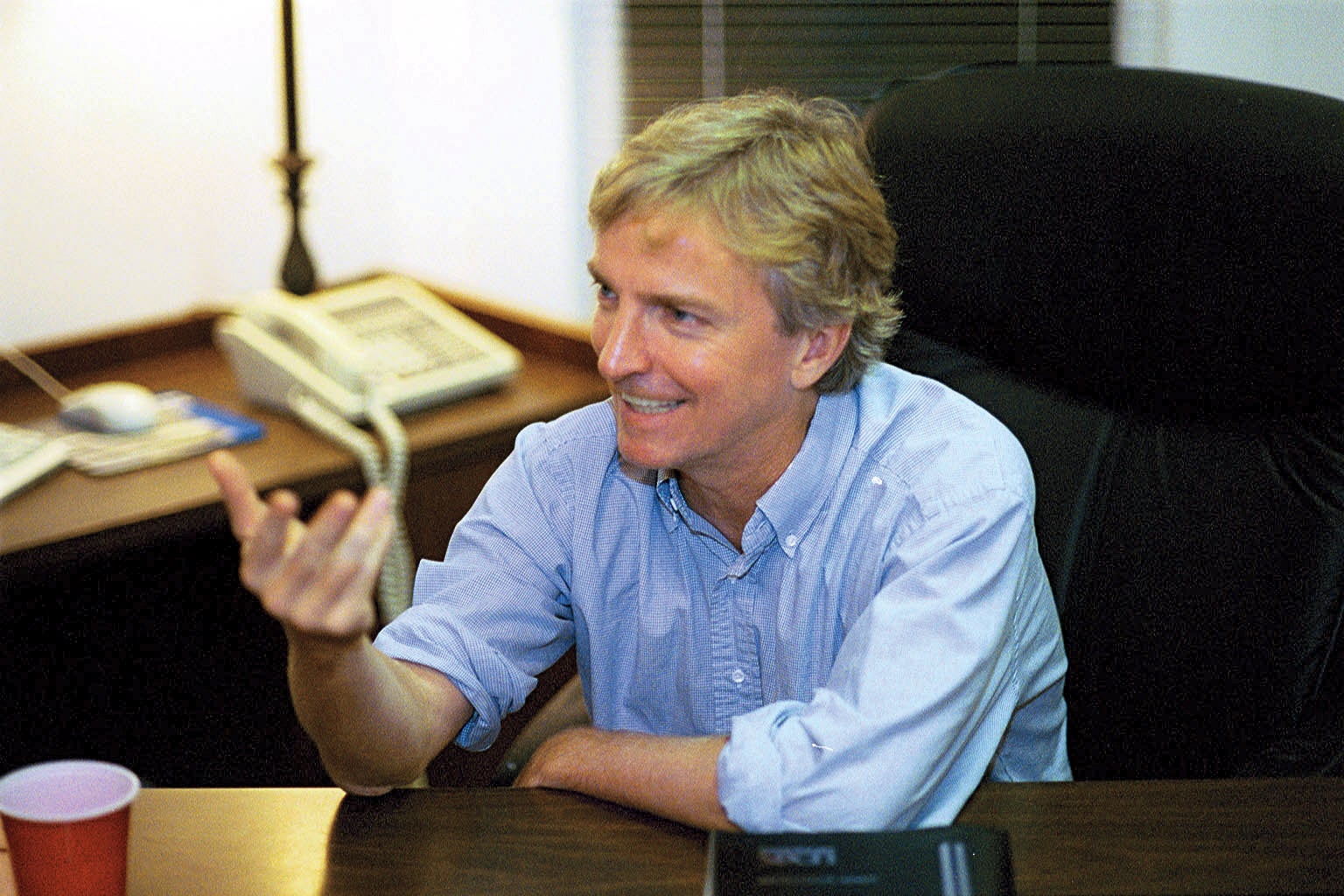

McDuff has spent his career answering that last question for himself, for the last 20 years running his own law office in Jackson, Miss., where he takes on a mix of criminal and civil cases, most involving civil rights issues. “If it’s something that interests me and that I think is important—and if I think I can make a difference—I’ll take it on,” he says.

Recently, McDuff has worked on several cases involving teenagers prosecuted as adults. He represented one of the defendants in the Jena Six prosecution in Louisiana, in which six African-American students were charged with attempted murder for allegedly beating a white student after nooses were hung outside their school. McDuff helped forge a resolution whereby all felony charges were dismissed and the teenagers’ records were expunged. In an ongoing case, he is appealing the conviction of a 14-year-old boy sentenced to life in adult prison in Mississippi for a robbery-murder in which he was not the trigger person and was unarmed. McDuff is also representing a Mississippi girl who became pregnant at 15 and had a stillbirth. A fetal autopsy revealed traces of cocaine, and the girl is now being prosecuted for murder.

“If it’s something that interests me and that I think is important—and if I think I can make a difference—I’ll take it on.”

Robert McDuff ’80

Voting rights is another important issue for McDuff. Early in his career he worked for the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law in Washington, D.C., focusing on voting issues. One of his cases, Clark v. Roemer, went to the Supreme Court, where he successfully argued that aspects of Louisiana’s election system for state court judges violated the Voting Rights Act. That case led to the redrawing of a number of the state’s judicial election districts, which helped push the number of African-American judges in the state from six out of 230 to more than 40. (He has since argued three other cases in front of the Supreme Court.) He was co-counsel in a similar case in Mississippi that led to a dramatic increase in the number of African-American judges there. Over his years practicing in the South, McDuff has seen the voting rights of African-Americans improve substantially. Yet civil rights issues remain, and he feels it’s essential that someone keep watch: “I’ve seen white public officials take the attitude, ‘Oh, we’ve solved these problems.’ But many of the problems are still there. And it’s very easy to backslide once the attention goes away.”

McDuff runs his practice out of a small blue house half a block from the Mississippi Supreme Court, where he’s argued many cases. These days, though, he does much of his work via cell phone and laptop from New Orleans, where his wife, Emily Maw, is the director of that city’s branch of the Innocence Project. Such flexibility is part of what McDuff enjoys about having his own practice. “Private practice has its rewards. There are very few sorts of organizations that allow the flexibility and variety I have with these cases,” he says.

Over the years, McDuff has hired several interns from Harvard Law School. One of them, Jacob Howard ’09, is returning to Jackson in the fall to work with him full time. “He’s had a huge impact on who and what I want to be as a lawyer, simply because of the way he’s chosen to practice law,” says Howard. “He could have done any number of things, but he went back to Jackson to open up this tiny office and take cases just because he thinks the work is important.”