Ask the Professor: Kenneth Mack ’91

Some say the Clinton-Obama fight reflects a historical tension between blacks and women in the struggle for equality. A legal historian says the truth is not so simple—and far more interesting.

The Clinton-Obama battle can’t be characterized—as many commentators have asserted—as a continuation of a historical struggle over who should go “first,” or as a competition in the “oppression sweepstakes,” because the underlying premise itself—that there has been a political struggle between African- Americans and women—is an oversimplification.

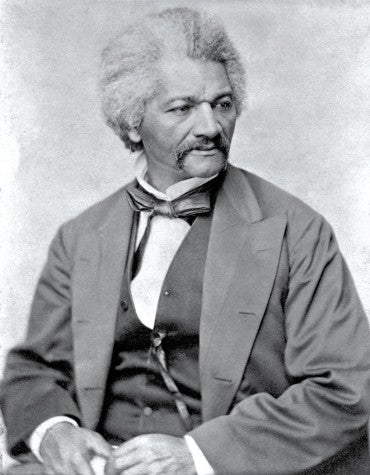

It’s certainly true, as some have pointed out, that after the Civil War, when the 14th and 15th Amendments were being framed and ratified, the black abolitionist Frederick Douglass and the white feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton debated whether African-Americans or women should be guaranteed the right to vote. But the enfranchisement issue wasn’t simply a competition between black men and white women. At the time of the Douglass-Stanton debate, there was a split within the feminist movement itself. The group that formed around Stanton opposed the 15th Amendment because it enfranchised black men but not white women, while a rival group of prominent feminists supported the amendment. Black women feminists such as Sojourner Truth were pulled in both directions, but Truth and her peers ultimately supported Stanton’s opponents. Both feminist groupings claimed a mandate as the national feminist organization, and each saw itself as the true successor to the legacy of the antebellum woman’s movement.

Likewise, some observers of the Clinton-Obama contest have recalled the 1960s as another moment when African-Americans and women competed for equality. For instance, the nation’s highest-profile feminist organization, the National Women’s Party, opposed the original version of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 for its failure to include protections for white women. The act’s prohibition on sex discrimination was added at the behest of Howard Smith, a segregationist congressman who had a longtime association with the NWP. But it is also true that once sex equality was added to the bill, it was kept there in part through the efforts of Pauli Murray, a black woman lawyer and feminist activist, who wrote a memorandum in support of the amendment and distributed it to every member of Congress.

After the bill became law, Congresswoman Martha Griffiths criticized the slowness of the federal response to gender discrimination, arguing that the government had an “unconscious desire to alienate women from the Negroes’ civil rights movement.” “Human rights,” she asserted, “cannot be divided into competitive pieces.” Such sentiments led directly to the formation of the National Organization for Women by an interracial group of feminists, including Murray and Betty Friedan, quickly displacing the NWP as the premier feminist organization. Like its 19th-century forerunner, the ’60s-era push for gender and racial equality in law drew its participants across the boundaries that we tend to impose on the past.

There are far more interesting questions to ask about the Clinton-Obama battle than the simple ones that frame themselves around the question of black men versus white women. Obama proved he could draw strong support not only from Southern states with large black populations, but also from Western states with overwhelmingly white ones. Similarly, most pundits conveniently ignore the fact that Clinton retained the support of the bulk of the African-American political leadership even after black voters began moving toward Obama.

This coming year, Professor Kenneth Mack ’91 will teach courses in American legal history, the civil rights movement, and critical race theory. He is completing a book, titled “Representing the Race: Creating the Civil Rights Lawyer, 1920-1955,” to be published by Harvard University Press in 2010.