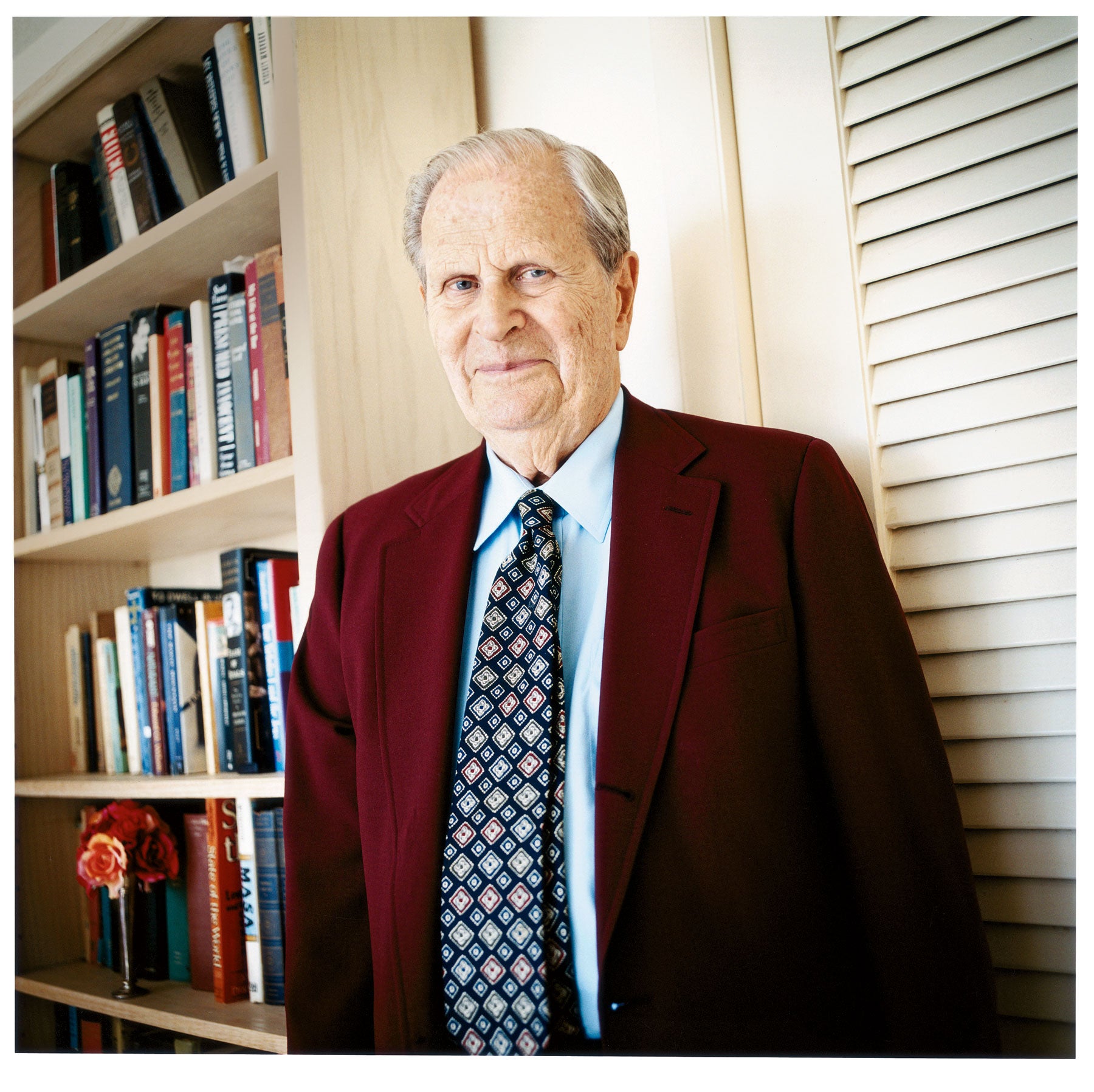

At the top of his game, Melvin Kraft ’53 switched to a new one

A few years ago, HLS Professor Richard D. Parker ’70 sat down to read a draft of a novel-in-progress by a retired commercial litigator, Melvin D. Kraft ’53.

Parker was immediately captivated.

“Most modern fiction is about love, usually the failure of love. But there is very little about work,” said Parker, who teaches a popular seminar on law and literature that focuses on the spiritual aspects of professional work. “It’s particularly hard to write about [work] in a way that isn’t flat, superficial and negative.” That’s where Kraft’s novel, “His Sole Weapon,” stood out.

“What struck me was its tone–a tone of gentle intensity,” said Parker. Although the book focuses on two trials, it includes none of the usual accoutrements of the typical legal novel: sex, violence, detailed explanations of police procedure. Instead, it tells the story of a brilliant young lawyer who tries a major corporate case, then finds unexpected satisfaction in a court-appointed immigration fraud case. The “sole weapon” referenced in the title is the truth, and the story explores the lawyer’s deep love for the law and its capacity for imposing order on chaos.

For Kraft, who began working on the novel eight years ago when he was 72 years old, the story line came naturally. In the mid-1960s, when boutique litigation firms were rare, Kraft, hungry for independence from law firm life, opened his own practice in Manhattan. For two decades he tried cases on behalf of numerous major corporations, including Mobil Oil, and he was often called in by major Wall Street firms to join their litigation teams. Like the hero of his novel, Kraft loved the intellectual stimulation of those trials. But it was a court-appointed habeas corpus case on behalf of a young man convicted of rape and robbery that fed his soul.

The petitioner, serving time in a New York state penitentiary, claimed that his legal aid lawyer failed to subpoena four alibi witnesses. Kraft got the lawyer’s file, found his client’s claim was true, and presented the testimony of the alibi witnesses at the habeas corpus hearing. It was a mistaken identity case, says Kraft. The petitioner was a young black man, and the people who testified against him were white. Kraft got the conviction reversed, winning praise from Judge Marvin E. Frankel and a story in The New York Times. Kraft didn’t make a penny on the case but found the satisfaction incomparable.

“It’s that case that left me with very good feelings about myself, my role in the system, my feeling about honesty in the law and my confidence in the law,” said Kraft. “I feel a great deal of professional pride, which aren’t the words I mean to use. Because I felt something deeper than that, something more rewarding.” It was that feeling that he set out to capture in “His Sole Weapon.”

Kraft retired from his trial practice in 1988, when he was 62. He went on to teach dispute resolution at MIT’s Sloan School. At the same time, he started toying with the idea of writing a novel that reflected his experiences, but he was discouraged by a journalist friend who insisted his idea wouldn’t work because it didn’t include a murder.

Kraft eventually decided his friend was wrong. “I think you can tell an interesting story about the daunting problems intelligent people face in their lives and careers.”

And although he had never before tried his hand at fiction writing, he started in earnest in 1998, and put the same intense focus into his avocation that he’d applied in his legal work.

When Kraft met Parker on the recommendation of mutual friends, they immediately hit it off. Parker has served as Kraft’s writing mentor, while in turn coming to admire his new friend’s approach to life and the law. “He made the decision to stop when he was at the top and then to undertake a major new project at this point in his life,” said Parker.

Kraft hopes to attract the attention of a publisher. In the meantime, he said, “I’m sort of taking it easy and enjoying life. Now that I’m 80, I think it’s time to sit back.”