Is the president “above the law”?

Fifty years ago, the Supreme Court heard one of the most consequential cases on the limits of executive privilege — that is, the chief executive’s right to keep certain information private, even from other branches of government. In United States v. Nixon, decided on July 24, 1974, a unanimous Court declared that although a president’s communications are entitled to a great deal of protection, that protection is not “absolute.”

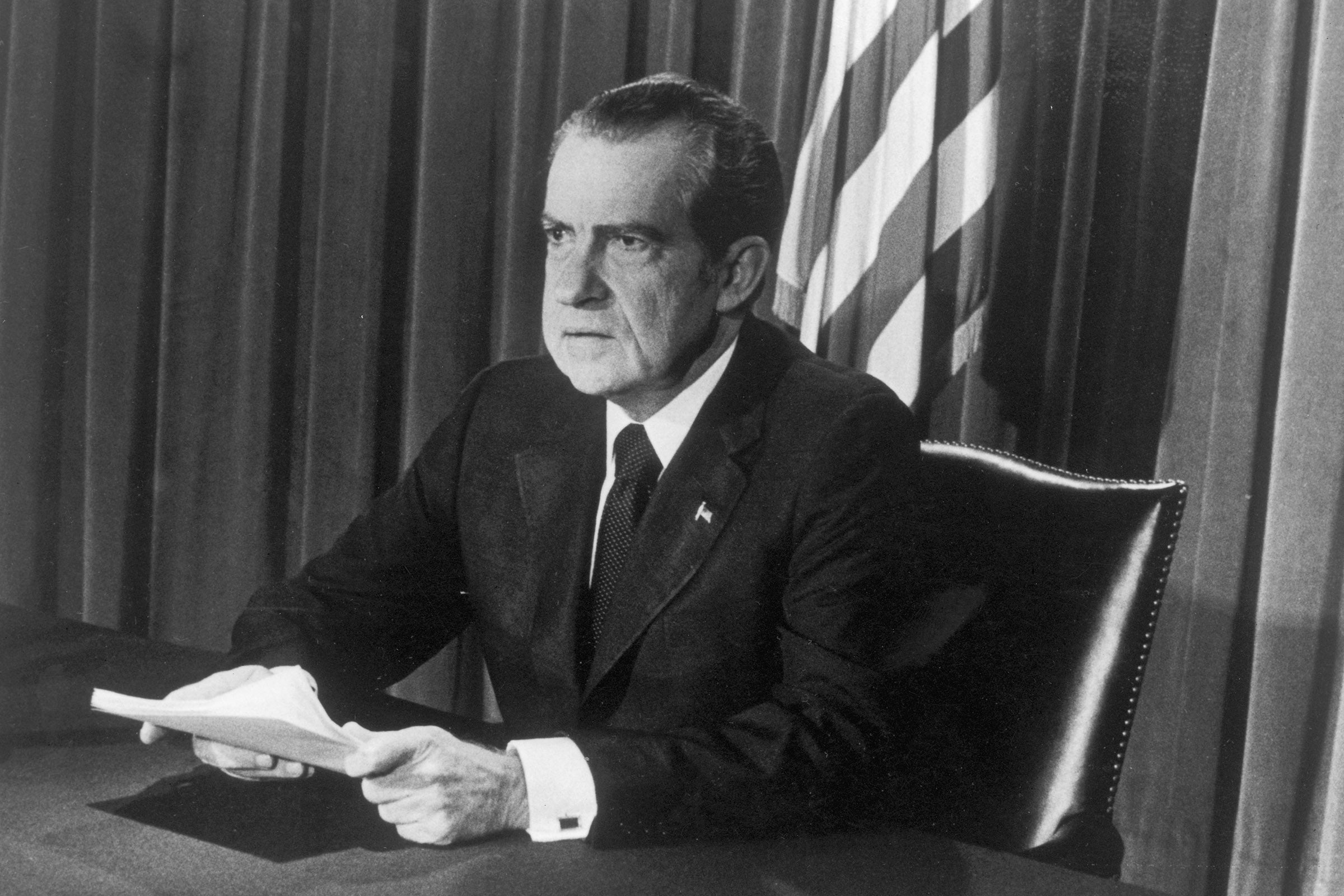

The case emerged out of the Watergate scandal, which involved a 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Headquarters by individuals connected to President Richard Nixon’s reelection campaign, and the cover-up that followed. Several administration officials were fired or resigned during the subsequent investigation, leading to the appointment of a new special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, who ultimately obtained a trial subpoena for the audio tapes the president made of his conversations with administration officials and others, as well as other materials thought to be relevant to the probe.

Nixon turned over some of the demanded items — but not all of them. After a district court refused to throw out the subpoena, the president appealed directly to the Supreme Court, arguing that the requested tapes were protected communications between the president and members of his administration.

But in a unanimous decision — made without Justice William Rehnquist, who, as a former member of the Nixon administration, recused himself from the case — the Supreme Court rejected the president’s arguments.

“Neither the doctrine of separation of powers nor the generalized need for confidentiality of high-level communications, without more, can sustain an absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances,” wrote Chief Justice Warren E. Burger. Quoting from a trial court decision by Chief Justice John Marshall in an 1807 treason case against Aaron Burr, Burger added that “Marshall cannot be read to mean in any sense that a President is above the law.”

What effect did U.S. v. Nixon have on Nixon himself — and on subsequent occupants of the Oval Office? And five decades later, how does it square with the Court’s recent decision in Trump v. U.S., which determined that presidents are entitled to expansive immunity from criminal prosecution?

The case, which precipitated Nixon’s resignation on August 9, 1974, was “a big deal,” says W. Neil Eggleston, a lecturer at Harvard Law School and former chief legal counsel to President Barack Obama ’91 and associate counsel to President Bill Clinton. According to Eggleston, who teaches a course on presidential power, the Court devised a balancing test for when presidential communications are subject to subpoena — and “we never quite know how a court is going to come out.”

In an interview with Harvard Law Today, Eggleston described the impact of the landmark decision and why it both does — and doesn’t — conflict with the current Court’s holding in this year’s case against former President Donald Trump.

Harvard Law Today: What were Nixon’s arguments for why he should not have to turn over certain items that were demanded by the special prosecutor?

Neil Eggleston: His position was that the decision about whether the material was protected by executive privilege was a decision that was entirely committed to the president, that he was authorized to make the decision, and that the Court had no power to interfere with or review that decision.

HLT: What were the special prosecutor’s arguments?

Eggleston: The arguments that were made are quite similar to the ones that the Court then adopted. First, you have to remember that Nixon was not a defendant. He was not indicted — a number of his aides were indicted. This is after Archibald Cox [LL.B. ’37] had been fired and Leon Jaworski had been selected as the new special prosecutor. Leon Jaworski had issued a trial subpoena to get the tapes in connection with the prosecution of several of Nixon’s aides who were already under indictment.

The argument that Jaworski made — and that the Court ultimately adopted — was that the criminal judicial process was paramount. That, in the criminal judicial process, the courts are entitled to every person’s evidence, and that, as a result, the court would be the entity to decide whether the material had to be turned over or not. The Court ultimately rejected the notion that that was a determination that only the president made and the court had no role in.

The Court did say that, when the president makes a determination that materials are protected by executive privilege, the materials are what the Court called “presumptively privileged.” But it went on to adopt a balancing test to determine whether the material had to be produced in any event.

HLT: Why else was the Court’s decision significant?

Eggleston: The Court adopted this by a 9-0 vote. It was a big deal at the time, because it was written by Chief Justice Warren Burger, for whom I clerked several years later. Burger had been appointed chief justice by President Nixon, so the fact that it was written by him and was 9-0 was important to having the public recognize that the Court had treated the matter seriously and fairly.

HLT: Could you tell us more about that balancing test? How did the Court distinguish between things that could be kept confidential and things that have to be turned over on subpoena?

Eggleston: The Court laid out a balance between a potential showing of what it referred to as “a demonstrative need for use in the criminal trial” with what it called a “the president’s generalized interest in confidentiality.” But describing the president’s interest as a “generalized interest in confidentiality” doesn’t sound so weighty.

The Court did say, obviously, that presidents need confidentiality. The president needs to be able to talk to his or her staff and advisers in order to get the best advice, and the Court took the position that the likelihood of receiving the best advice would be undermined if people thought that whatever they said to the president would or could be disclosed. But, keeping in mind the Sixth Amendment right to a trial, the Court said the paramount interest of getting to the right answer outweighed the more generalized interest that the president has in keeping communications with aides confidential.

HLT: How did the Court justify imposing a limit on executive privilege?

Eggleston: Essentially, it said that the interest of getting this information in connection with a criminal trial involving several defendants who were facing incarceration was more important than this amorphous interest in presidential confidentiality. It’s important to note that this rule really only applied to the criminal justice system. That was a Rule 17 trial subpoena. In later cases, the courts — not the Supreme Court — applied this analysis to grand jury subpoenas. But the same balancing test has never been held to apply to congressional subpoenas, for example. The Court and later courts determined that the impact on presidential confidentiality, from the very remote possibility that there might be a grand jury subpoena or a criminal trial subpoena calling for the information, was sufficiently remote that it would be quite unlikely to impact the president’s ability to get confidential advice from his or her advisors.

HLT: What was the impact of this decision on Nixon? What about the office of the presidency afterward?

Eggleston: Nixon resigned a couple of weeks after this opinion came down. When he learned that he was going to have to turn these tapes over, he decided that his presidency was no longer tenable. So, the impact on him was immediate and significant.

“Although [U.S. v. Nixon and Trump v. U.S. are] not directly at odds, the way the Court looked at the role of the presidency and our constitutional system could hardly be more different.”

HLT: And what about the office of the president?

Eggleston: For the presidency more generally, whenever there’s a balancing test, we never quite know how a court is going to come out. When I was serving as White House Counsel under President Obama, we didn’t have anything that bordered on criminal issues. But I knew that I couldn’t quite assure the President that all our conversations were entirely confidential and that I could never be compelled to reveal them. I don’t know that it really impacted our day-to-day, but there was always a level of uncertainty.

I was also in the White House Counsel’s office during the President Clinton’s first term and stayed on from the outside to assist him with the Ken Starr investigation. That was more of a realistic issue, because President Clinton was under criminal investigation by a grand jury. In that case, I couldn’t really assure him that our communications would necessarily be protected.

When President Trump was under investigation during the course of his administration, I suspect that the White House lawyers had to tell the president that they could not promise him that their communications would be confidential. And indeed, they were not: I think a number of lawyers actually ended up testifying before the grand jury.

HLT: How does Trump v. U.S. square with the Nixon case? Can it?

Eggleston: They’re not on exactly the same issue. The only place that they’re near the same issue is Judge Aileen Cannon’s determination to dismiss the case on the grounds that special prosecutor Jack Smith was not properly appointed. There are a couple sentences in U.S. v. Nixon that resolved that issue adversely to the decision that Judge Cannon rendered. However, she wrote that the Supreme Court language was dicta [or not legally binding], and she didn’t have to follow it.

Apart from that, they’re not technically at odds with each other. But in the following sense, I think they see the presidency quite differently: the Nixon case made clear that the notion that the president’s communications are absolutely privileged and cannot be reviewed by a court was wrong. It determined that President Nixon was a witness, just like any other witness in connection with a criminal trial. But in the Trump immunity case, the Court took the opposite view, essentially determining that the criminal laws don’t apply to the president at all, as long as official conduct is involved. So, although they’re not directly at odds, the way the Court looked at the role of the presidency and our constitutional system could hardly be more different.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.