An Italian friend of Mary Ann Glendon’s advised her that the first thing to understand about the Vatican is that it is a court, the Roman Curia, headed by one man with supreme authority. As Glendon quips, she was one of the “few ladies” serving in a court with “many lords,” a member of the laity “in a culture dominated by clergy, an American woman in an environment that was largely male and Italian, and a citizen of a constitutional republic in one of the world’s last absolute monarchies.”

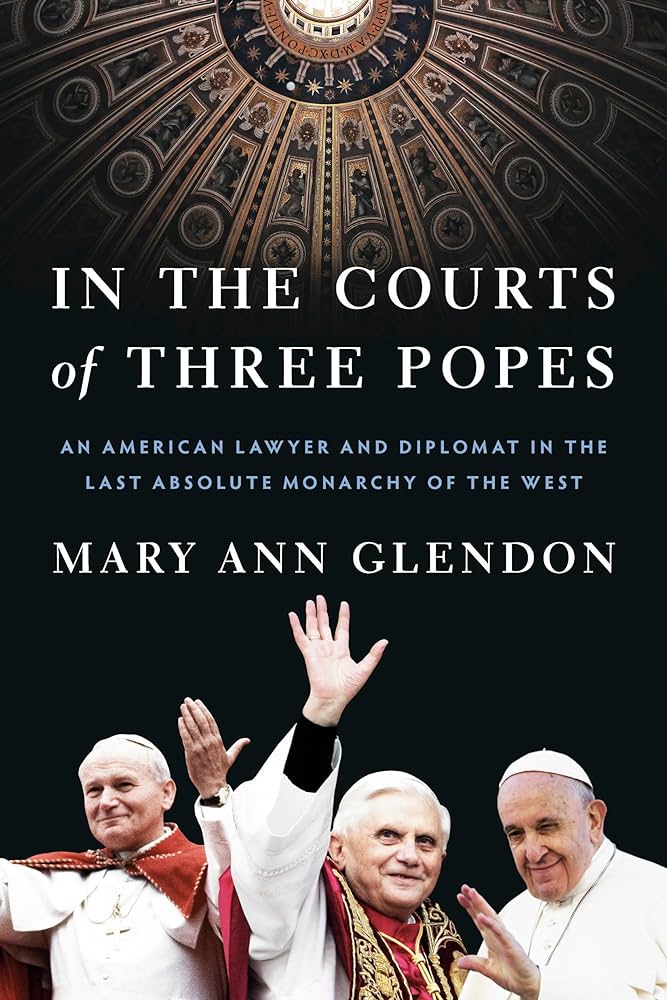

In her book “In the Courts of Three Popes: An American Lawyer and Diplomat in the Last Absolute Monarchy of the West” (Image), Glendon, Learned Hand Professor of Law Emerita at Harvard Law School, shares her experiences with the Holy See and her observations on how “three very different popes” navigated the challenges of a rapidly changing world.

Glendon touches upon her childhood in western Massachusetts and her path to a professorship at Harvard before turning to her assignment to lead the Vatican delegation to the United Nations’ Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995. After studying essays and talks by then-Pope John Paul II that she found adopted the language of modern feminism, she gave an opening statement calling attention to women’s inadequate primary health care, as well as poor nutrition and sanitation, which she contends were underemphasized because of the conference’s “fixation” on reproductive health. She also relates warm personal encounters with John Paul II, who dreamed of “a reinvigorated Church whose presence would be more meaningful in a world that had profoundly changed since Vatican II,” the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s that sought to modernize the Catholic Church.

During the papacy of Pope Benedict XVI, Glendon was nominated by President George W. Bush in 2007 to become the U.S. ambassador to the Holy See. Her life changed drastically, as she was guarded by security personnel and was on call around the clock. Benedict expressed views about religion in public life and safeguarding traditional marriage that mirrored Bush’s, according to Glendon. She also discusses the pope’s visit to the United States as well as Bush’s visit to the Vatican. That the president and pope met three times in a little over a year, she writes, was indicative of the closeness of their relationship.

In the wake of Benedict’s retirement in 2013, Glendon was appointed by Pope Francis to a commission charged with assessing the scandal-ridden Vatican Bank. Shortly thereafter, her husband, Edward, died unexpectedly. She threw all her energy into her work amid her grief and shock, she writes, although her more than four years on the commission were “spent in often fruitless labor on reform” of the institution.

After her years of service, Glendon acknowledges that the Curia “still has a long way to go” to achieve complementarity between clergy and laity, and between men and women. And she shares her belief that Catholics worship not a church or its ministers but a loving God.