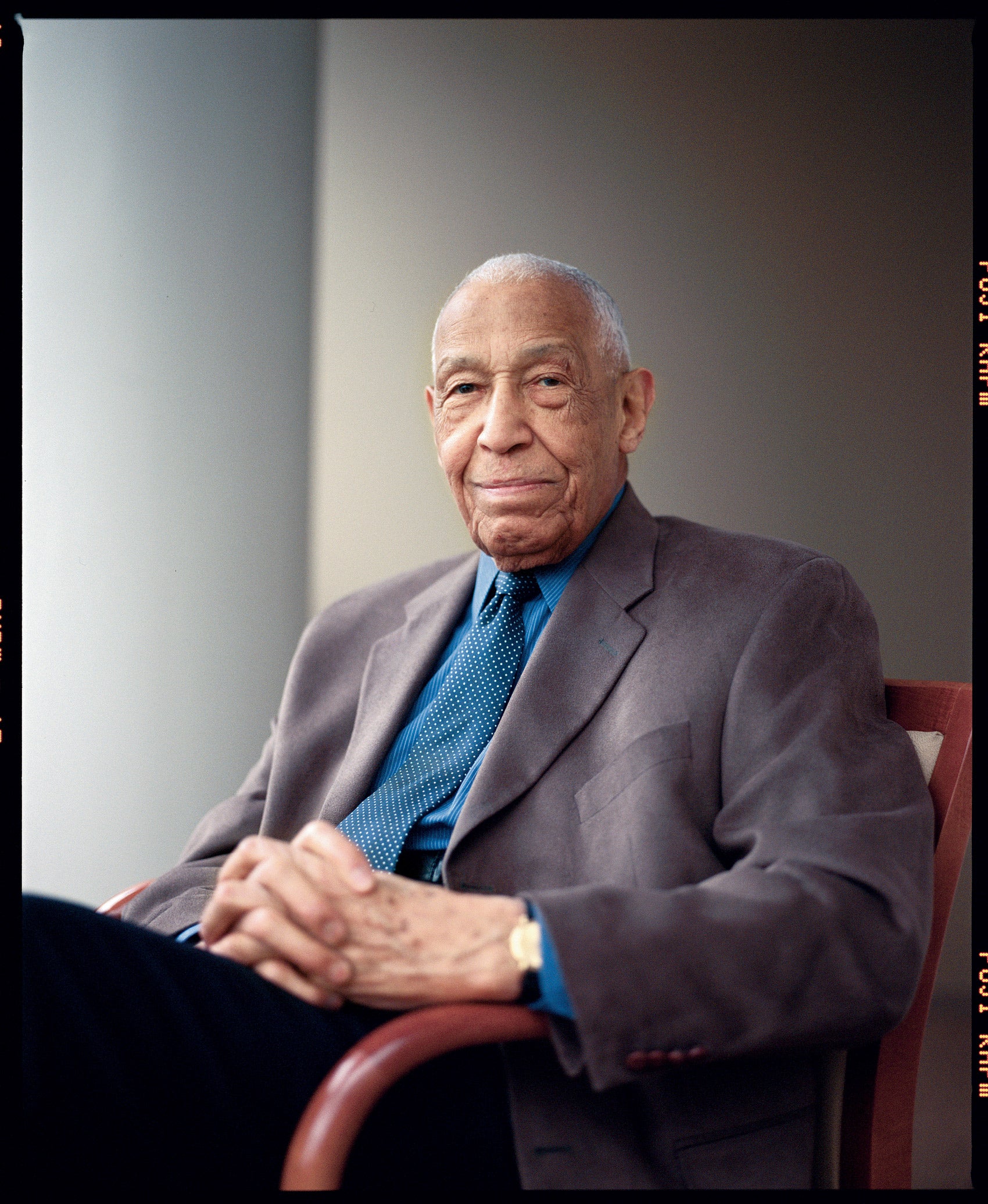

George Leighton ’43 (’46) spent his childhood in Massachusetts summering in Plymouth and wintering in New Bedford. His summer home was a shanty with no running water or electricity near the cranberry bogs, and his winter home was an unheated apartment near the textile mills.

From his modest beginnings as the child of Cape Verdean immigrants and armed with only a sixth-grade education, Leighton made his way through Howard University to Harvard Law School to become a leading civil rights attorney and a federal district court judge.

Born George Neves Leitao on Oct. 22, 1912, he was renamed George Leighton by a fourth-grade teacher who couldn’t pronounce his surname. He had to leave school at the beginning of seventh grade to work on an oil tanker.

Surrounded by “drunken, dangerous men,” he hated life at sea. His seafaring days ended in violence in a New York City port when the steward abandoned ship, leaving Leighton, the cook, with no provisions. Under attack by a mutinous crew, Leighton escaped by hiding in a docked tugboat.

As a young boy, Leighton’s favorite book was the Sears Roebuck catalog. But growing up, he read extensively and taught himself math and history. He returned to school at night in the 1930s, and in 1936, he won a $200 scholarship in an essay-writing contest. Setting his sights on Howard University in Washington, D.C., Leighton passed the school’s entrance exam, but, without a high school diploma, he wasn’t immediately enrolled in the degree program. His lack of a diploma also caused the scholarship committee to make his award contingent on completing his studies in good standing. By the end of first term, he was on the dean’s honor roll, where he remained, graduating magna cum laude in 1940.

Knowing that some of the great African-American lawyers had graduated from Harvard, Leighton was determined to go there. He approached Howard University Dean William Hastie ’30 S.J.D. ’33 and later received a handwritten note from HLS Dean James Landis ’24 inviting him to stop by the next time he was in Cambridge. The following Saturday, Leighton was in Landis’ office. Leighton remembers the dean’s “laser-beam brown eyes” fixed on him as he poured out his life’s story. After finishing his monologue, Leighton didn’t know what else to do but take his coat and hat and leave. He later learned he was accepted to HLS on a full scholarship.

“I remember sitting in Austin Hall, poor as I could be, rubbing shoulders with the wealthy sons and grandsons of some of the greatest lawyers in America,” said Leighton. Although it was hard work, he says, his years at Harvard gave him a sense of satisfaction that has never left him.

After law school, he moved to Chicago. In the 1950s, he was president of the Chicago NAACP and was chairman of the organization’s legal redress committee during the Cicero riot case. He represented Harvey Clark, an African-American, who, according to Leighton, “had the temerity to rent an apartment.” Leighton advised Clark that he had a right to move into Cicero, a white suburb of Chicago, but a mob burned the building down to prevent the move, and Leighton was indicted for conspiring to start a race riot.

“They did me a big favor,” said Leighton. “They taught me how it felt to be wrongfully accused.”

Several years later, with the help of Thurgood Marshall, then general counsel of the NAACP, the indictment against Leighton was dismissed.

In 1964, he was elected a judge of the Circuit Court of Cook County, and later, a justice of the Illinois Appellate Court, First District. After being nominated by President Gerald Ford, he was appointed a U.S. district judge for the Northern District of Illinois in 1976. He retired in 1987, and at 92, he’s of counsel at Neal & Leroy in Chicago.

Leighton regularly returns to New Bedford to take his “sentimental journey,” and several years ago, he bought a summer home in Plymouth with a small cranberry bog in back.

“The place where you have suffered a lot, cried a lot,” said Leighton, “that place becomes precious.”