HLS hosted the fourth Celebration of Black Alumni in September, featuring the theme “Turning Vision into Action.” The actions of alumni who attended have resonated in courtrooms and classrooms, in elected office and the corner office, in communities and in the culture. The Bulletin spoke with five CBA participants about where their vision has led them and where they hope to yet go.

***

Debra Lee ’80

The chair and CEO of BET Networks, which provides entertainment for a primarily African-American audience, Debra Lee J.D./M.P.P. ’80 has worked for the organization for 30 years, rising from general counsel and COO. Over the years, the network has evolved but her mission to serve her audience remains unaltered.

Her perspective of her time as a student at HLS:

I think it was still hard during the late ’70s to be an African-American at Harvard Law School and to be a woman at Harvard Law School. There weren’t a lot of professors then who really thought a lot or cared a lot about issues that were important to me as a black female. I have to admit it was a difficult time to go to Harvard, and you may remember it was a difficult time to be black and to be in Boston. Boston was going through the school desegregation cases, and we were told as black law students that there were certain parts of Boston that you couldn’t go to. So even though I’m from the South, that was very alarming to me. It was a tense time, but we had a cohesive group of students and nice support groups to help you manage through the environment.

I’ve heard it’s changed a lot over the years.

She took a job at BET in 1986, a few years after its launch, leaving the law firm Steptoe & Johnson:

“My father said, ‘You’re doing what?!’ But in hindsight, it was the best decision I could have ever made.”

It was very risky. I felt like for the first time I was stepping off the fast track. I’d gone to Harvard Law, I’d done a clerkship, I was working for a corporate law firm and now all of a sudden I was going to work for a small, black-owned company that not many people had heard of. I was so excited about what BET did—the fact that they provided programming for the African-American community, the fact that I had grown up on great brands like Ebony and Motown and Essence. I decided that it was worth taking the risk and hoped that it worked out. My father said, “You’re doing what?!” But in hindsight, it was the best decision I could have ever made.

She said she brings a different voice to the job of CEO as a woman, including an emphasis on strong female characters in programming:

I realized early on I’m in this position for a reason. Because of who I am. And I shouldn’t run away from that. I shouldn’t try to manage like a man or how I think a man would do it. I have to be myself. And either I will be successful doing that or I will fail, but I have to be true to myself and what’s important to me.

She is one of few women or minorities serving as leader of a large company:

We’ve been talking about diversity for 30 years, and we’ve been talking about getting more minorities and women in upper-level positions, and it just hasn’t happened. And I find that distressing. And I think people in these positions, the CEOs and the COOs, just really have to commit to bringing someone along with them. In some companies that just doesn’t happen because all the executives look the same, usually white males. I’m really proud of what we’ve done at BET in terms of training minority executives and female executives and giving them opportunities that they may not have had at other places. But that old boy system is really hard to break.

Television now features far more diversity in its programming than it did when BET began, but the network still carves out its own niche:

We know our audience better than anyone else. So our goal is to produce programming that is the highest quality that competes with anyone else out there, that can be an authentic voice for our audience. We try to stick to what we do and compete. I remember someone once told me that competition helps make the leader stronger. And I think that’s happening in our case. We are definitely still the leader. It’s a little more competitive right now. That’s good. We’re up to the challenge.

***

Gina Clayton ’10

Gina Clayton ’10 has been fighting for social justice her entire adult life, starting when she was a youth organizer for the NAACP as an undergraduate student at the University of Southern California. Now she is running her own nonprofit, Essie Justice Group in Oakland, California. Started with the help of a 2014 HLS Public Service Venture Fund seed grant, the organization seeks to empower women whose loved ones are incarcerated and to end mass incarceration.

On the significance of the Celebration of Black Alumni:

I didn’t know anybody that looked like me that went to a school like Harvard. That was just not a reality for me. That’s the importance of convening events like this. It’s to remind us and others who are just as exceptional from communities that are often left out, that this is possible.

She grew up in Los Angeles, the child of a mother from Holland and an African-American father:

The spark for civil rights and social justice really came from the deeply personal experience of growing up in worlds that are different and trying to navigate both worlds. My entire life navigating the intersections of race, ethnicity, nationality, and culture has meant that I’ve seen inequality in such a stark way from a very early age and also have been disturbed by it. I think all those things gave me a passion since I was very young for wanting to make things fairer for people.

Her interest in mass incarceration is political and personal:

When I got to Harvard, my very first year there, someone I love was sentenced to 20 years in prison. This was an eye-opening, transformative, really deeply painful experience that caused me to apply a laser focus on what mass incarceration is doing to families, to communities, and to this country today.

On the Essie website is this statistic: Nearly 1 in 2 black women has a family member in prison:

I began by asking the question: What is mass incarceration doing to women in the country when the numbers are so high? We know there’s an emotional and mental health toll; we know there’s an economic consequence. Surely this is creating all kinds of gender inequality in the United States. No one else was doing it, in terms of organizing this particular group of people. That made it clear. We needed to start our own shop.

The organization offers a nine-week program to women who have incarcerated loved ones:

“I imagine women outside of jails, courthouses, statehouses demanding change.”

By the end of the nine weeks, we see that not only do women break through their isolation but their mental well-being improves, their access to resources increases, and really importantly, they become civically active.

Women come to us as leaders already because they’re leading families, they’re navigating complex systems. We are redirecting and funneling that incredible expertise and energy where we as a society need it most, and that is in building solutions in our criminal justice system.

She plans to build a network of women across California and the country:

I imagine women outside of jails and courthouses and governors’ mansions and statehouses together arm in arm demanding change. And I imagine women as leaders of their communities to facilitate the healing we all need in the wake of 40 years of bad, inhumane policy.

I see myself as a builder, an organizer of communities, as a gender justice advocate. What I love about the work that I get to do every day is that it captures completely what my theory of change is. Real sustained change that really shifts reality for millions of people in a positive way happens when communities are uplifted, are given access to decision-making, are listened to. That kind of small “d” democracy is what I believe in.

***

Rory Verrett ’95

During his career, Rory Verrett ’95 has worked in policy, public affairs, and talent, including with the National Football League and an executive search firm. He is now a principal at The Raben Group in Washington, D.C., leading the firm’s sports practice, which seeks to promote fairness, equity and integrity within sports. He also hosts the Protégé career advice podcast.

The Celebration of Black Alumni is his favorite school event:

They are wonderful homecomings for some of my closest friends who happen to be some of the most accomplished people in law in America. I think the journey of African-American Harvard Law grads is somewhat unique. Just being able to check in at different stages of your career with people who are walking the same journey can be very uplifting, can help you see things with clarity in your own career.

He appeared on a CBA panel as an expert on career fulfillment. On his own career fulfillment:

What I’ve found is, if I can be in an influencer role with a positive outcome in an organization with a highly ethical and engaging culture, that’s when I’m at my most joyous, most engaging, most impactful state as a professional.

How he influences organizations:

A lot of the work that I do is in helping organizations understand the importance of diversity and inclusion and how it can impact what they do from a bottom-line perspective. And a lot of companies look at that as a legal and compliance issue: “Help me stay out of trouble.” Whereas I always approach it as, Here are markets, here are audiences, here are talented executives that you may or may not be accessing because you don’t have the competency and the capability to bring those influencers into your organization.

On athletes taking a public stand on social issues:

“A lot of players can be a little nervous about speaking out on social issues, but I think the rewards far outweigh the risks.”

I know a lot of players can be a little nervous about speaking out on social issues, but I think the rewards far outweigh the risks. Whether they accept it or not—and I think most of them do—they are role models for millions of people in America and around the world, particularly black and brown children, who will know who their favorite athlete is before they can recognize who the president is.

HLS Professor Charles Ogletree’s book “The Presumption of Guilt” included Verrett’s story about being mistaken for a car thief while in his own car. Another time, police officers threw him against a hood of a car while he was walking near his home wearing a Harvard Law sweatshirt:

I asked why they stopped me. “We’re looking for someone who stabbed a pizza guy two blocks away.” And I was wondering the whole time: Was he wearing a Harvard Law sweatshirt? But that stuff happens all the time. It’s happened to every black man I know multiple times. So it just reminded me that no matter your station in life, this could be an unfortunate reality of living in America.

The advice he’d give to someone who just graduated from HLS:

A Harvard Law degree is a very powerfully flexible credential. It can be an admission ticket to the legal establishment in America and around the world. Or it can be an insurance policy for you to take a risk in your career.

***

VIDEO: African Americans at Harvard Law School — a timeline

Produced for the 4th Celebration of Black Alumni, “Triumphant the Journey” highlights the history of African Americans at Harvard Law School, from the school’s founding and first admitted black students through the hiring of black faculty and the first Celebration of Black Alumni. The video debuted at the CBA in September 2016 and is narrated by Professors David Wilkins ’80, Kenneth Mack ’91, Annette Gordon-Reed ’83, and Charles Ogletree ’78.

***

Ted Wells ’76

A partner and co-chair of the litigation department at Paul Weiss, Ted Wells J.D./M.B.A. ’76 has successfully defended corporations in multibillion-dollar cases and public officials against high-profile charges. He also has done significant public service work, including with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and he was awarded the Charles Hamilton Houston Medal of Freedom at CBA.

He has attended every Celebration of Black Alumni:

So many of us see ourselves as part of a long line of black lawyers who were educated at Harvard and went on to participate in social justice causes. Many of us don’t see ourselves as having gone to Harvard Law for strictly personal gain, but rather to join a much larger legacy of trying to make America better, trying to racially integrate America, trying to work for social justice and equality.

He became close with Professor Derrick Bell, who taught him at HLS:

Professor Derrick Bell used to tell us that if we were going to work for corporate America, we should not get lost in corporate America. He said we had an obligation on the one hand to try to integrate corporate America and be participants in every part of the economy, but on the other hand we also had an obligation to play an active part in the African-American community. Part of his vision is that we would have people with social justice sensitivity who would sit on major corporate boards, who would be partners in major law firms, who would support our civil rights organizations.

African-Americans have made gains since the time he graduated, Wells says. And yet:

“Most major law firms now have one or two black partners. But the percentages are still extraordinarily low.”

The truth of the matter is that things have changed to a modest degree: Most major law firms now have one or two black partners. But the percentages are still extraordinarily low and increasing at only a glacial pace. So it’s not like we’ve had a big breakthrough that created a critical mass of black partners at big firms. It’s an ongoing struggle and hopefully at some point we won’t have to talk about such things. But that will probably be a long way from now.

His first multibillion-dollar defense was on behalf of Citibank:

It’s scary to stand in front of a jury and talk about the possibility of a jury returning a verdict against your client in the billions of dollars. It’s emotionally draining. I remember thinking that the whole Citigroup board is following my trial and that they had put their faith in me that I’d win the case. And I did.

If you win enough cases, people will find your telephone number and hire you for more cases.

On appealing to a jury when defending corporations:

It’s my job to strip away stereotypes about my clients so that by the end of a trial the jurors realize that whatever happened involves real people who have lives like anyone else and who should be judged based on the facts and not on their status as executives of major corporations. Corporations can’t do anything except through their people. So you’re always trying to humanize your clients.

He received a lot of attention for his investigation into what has been dubbed Deflategate, an alleged scheme by the New England Patriots to deflate footballs:

No comment on Deflategate.

He is at an age when many people retire. He is not retiring:

I like being a lawyer. I’m involved in the most interesting and complex cases in the country. I get up every morning excited about my cases and trying to find good solutions for my clients. I’m truly blessed. People talk all the time about trying to find a job that you love and that you’re passionate about. I have found a practice that I’m passionate about, and I appreciate how rare and fortunate that is.

***

Sylvester Turner ’80

Inaugurated as mayor of Houston at the beginning of the year, Sylvester Turner ’80 leads the fourth largest city in the nation, with challenges including city finances, pensions and infrastructure. A native of Houston, he previously served as a state representative and founded a law firm there.

In his inaugural address, he said that he doesn’t want two separate cities, of haves and have-nots. His initiatives include a program to assist the chronically unemployed:

Houston is a thriving, developing, dynamic city. But in the shadows of that economic prosperity, there are still many communities that are operating in the margins. We’re working to reduce that income inequality. We have to help people increase their skill set so they can take advantage of the job opportunities available in the city. Communities that have been overlooked and under-resourced for a long period of time we now have to give special attention to.

He is from one of those communities, the Acres Homes community—and he still lives there:

I think it’s important for kids in the same circumstances in which I grew up to see firsthand that you can be born and reared in that neighborhood, or neighborhoods that are similar, and still be successful, still rise up the economic ladder and still end up being the mayor of Houston. And I think I can demonstrate that more by example than just by rhetoric.

In a time of increased scrutiny of police relations with the African-American community, he is focused on building trust:

The community needs law enforcement, and law enforcement needs the community. We’re all on the same team working together and not at odds with one another. It’s important for the police department to be diverse from top to bottom. It’s important that we provide training on de-escalation, when police are confronting people out on the streets in the communities. I’m a very strong advocate of neighborhood community policing so that police can know people in the community and the community can know the police in their areas.

If at some point in time there’s an incident involving the police that people believe is unwarranted or unjustified, I think it’s important to speak very candidly, to be very transparent, to be upfront. But also it’s more important for people to see that you are in the neighborhood, that you are approachable, accessible and responsive, before those incidents occur.

His mother was a maid; his father died of cancer when he was 13. They raised nine children in a two-bedroom home:

“They said. … tomorrow will be better than today. Just keep working at it.”

They said that if we needed something and they didn’t have it, they would tell you they were sorry they didn’t have it. But tomorrow will be better than today. Just keep working at it. Education was the key to getting us a better future. And they were right.

My mom’s message was, We may not have lived in the biggest home, the high-priced home across town, but the neighborhood contained all the essential ingredients to make you successful.

He was part of the first wave of school integration, when African-American students from his neighborhood were bused to a white high school:

They were seeing us for the first time, and we were seeing them for the first time. It was like two universes—hot air and cold air—meeting at the same time, and that created a lot of friction, a lot of fights in the hallway. It was not good. But what we discovered is that once the parents got out of the way and allowed the kids to get to know one another, then over the next few years things started to settle down. We got to know them, and the white students got to know us, and we discovered that we had more things in common than otherwise. And as a result, by the time I was in the 12th grade, I was chosen president of the student body. From a rocky start, it turned out to be an excellent ending.

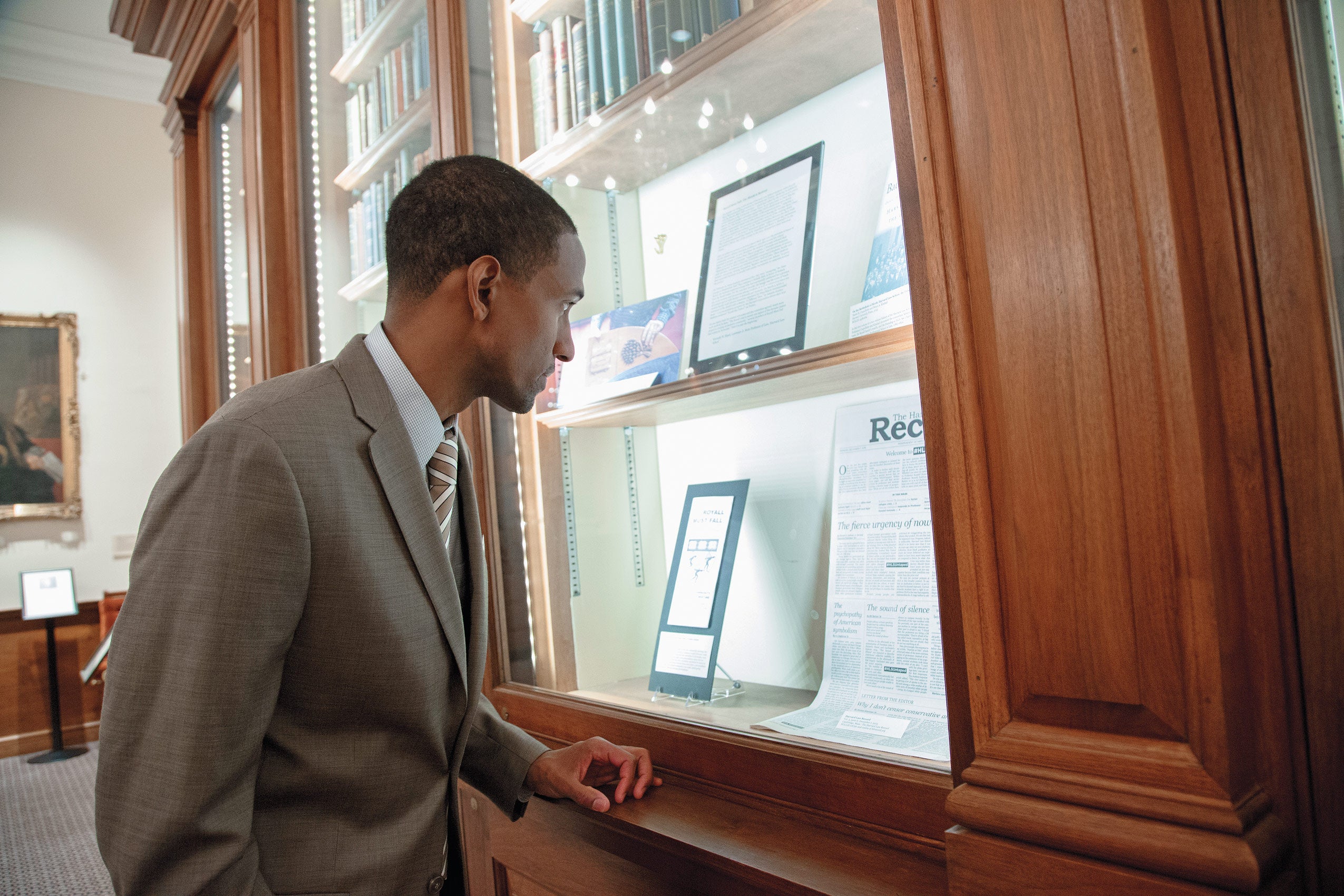

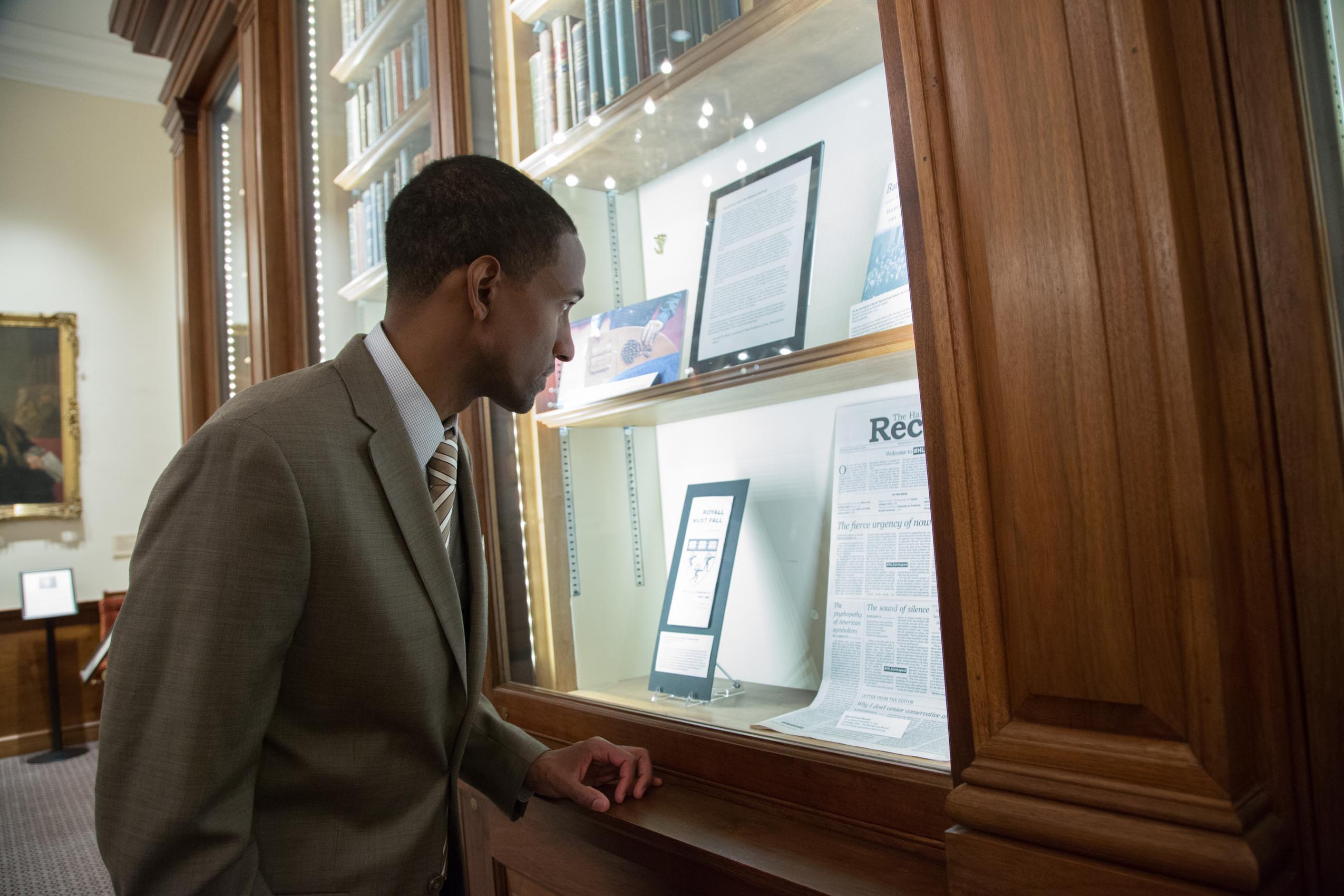

Vision Enacted: CBA IV