As a child growing up in Conroe, Texas, in the 1960s and ’70s, Annette Gordon-Reed experienced Juneteenth on different levels. She knew June 19 was the day in 1865 when enslaved African Americans in Texas were told slavery had ended — two years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. But it was also a time to run and play with cousins, throw firecrackers, eat barbecued goat, and enjoy unlimited access to iced-down bottles of red soda. “I remember a combination of childish celebrations and hedonism — and at the same time, a sense among older people that this was something important,” says Gordon-Reed ’84, the Carl M. Loeb University Professor at Harvard and author of six books, including “The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family,” which earned her a Pulitzer Prize in history and a National Book Award.

Annette Gordon-Reed presents a 360-degree view of the history leading up to Juneteenth, weaving in her perspective as a Black woman with Texas roots that run deep.

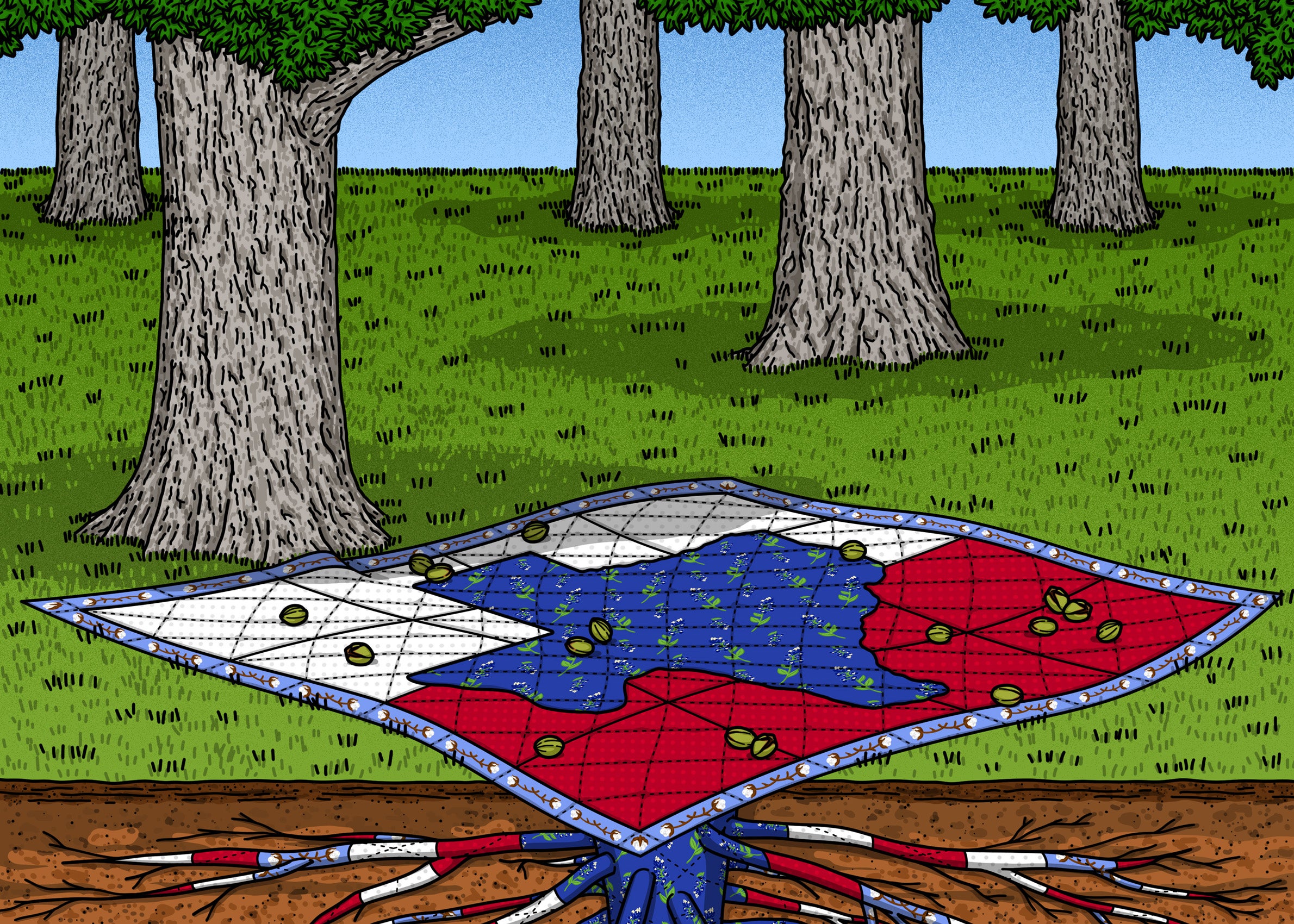

In the newly published “On Juneteenth,” Gordon-Reed presents a 360-degree view of the history leading up to the holiday and beyond, weaving in her perspective as a Black woman with Texas roots dating back to as early as the 1820s. White cowboys and oilmen are an indelible aspect of the Lone Star State’s mystique, fed by popular culture references ranging from the Hollywood epic “Giant” to primetime television shows like “Dallas” — yet the reality, as Gordon-Reed shows, is far more nuanced. Texas, she says, holds a unique place in U.S. history, with large Hispanic and Native American populations, a shared history with Mexico, the distinction of having existed as an independent republic, and a history of plantation slavery and legalized Jim Crow. “It’s a place,” she says simply, “where a lot of American things meet.”

On a more personal level, it’s also where Gordon-Reed grew up. The decision of Brown v. Board of Education was nearly a decade old when she entered kindergarten at Booker T. Washington High School, the de facto “Black school” that included students in grades K–12. Schools in Conroe remained segregated, for all intents and purposes, but Gordon-Reed’s father believed younger students benefited from attending schools separate from junior high and high school students — which was the case for the town’s white children. So it was that Gordon-Reed became the first Black student to attend Hulon N. Anderson Elementary.

“I learned later that my parents and the school district negotiated about how it would all proceed,” Gordon-Reed writes. “No fuss would be made. … I would just arrive at school and begin first grade as if there were nothing to it. There was, of course, something to it. This was a new thing in our little corner of East Texas.” Her family received death threats; lynchings and extrajudicial killings of Black men were a deep-rooted part of the area’s history, with little more than a generation separating one of the more recent cases and Gordon-Reed’s impromptu integration. Even so, she writes, her teachers treated her no differently.

The racism she did experience was more puzzling than anything else, as Gordon-Reed recalls. Some girls who were friends at school, for example, would ignore her in town. “You had to wonder, Why is it this way?” she says. “It created a detachment, a sort of anthropological approach to dealing with people.”

Gordon-Reed says it’s hard to know how much of that observational, outsider stance was already part of her personality and how much was cultivated by circumstance. Either way, she has used that power of observation as a historian committed to examining the accepted historical record to gain a more complex understanding of how people lived together.

Slavery in early American history, for example, is typically pegged to Jamestown and 1619, she notes, when in fact there is a record of its presence during the period of the Spanish exploration, when an enslaved man named Estebanico, originally from Morocco, traveled in the 1520s from Florida to Texas to what is now California. Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca described his invaluable ability to speak and translate Indigenous languages as the expedition made its way across the Southwest. “We didn’t spend much time on Estebanico in school, because that story is not tied to our Anglo-American heritage,” says Gordon-Reed. “But there’s no real reason to accept those boundaries. It’s useful to consider slavery as a global system and not limit our understanding to the 20 Black people who were brought to Jamestown in 1619.” Estebanico also offers the opportunity to consider an enslaved man as an individual, she writes, going well beyond the history taught to her as a young person. “Seeing Africans in America who were out of the strict confines of the plantation — and seeing them as other than the metaphorical creation of English people — would have pushed back against the narrative of inherent limitation. Africans were all over the world, doing different things, having all kinds of experiences.”

In the same vein, Gordon-Reed’s account goes beyond a dualistic understanding of slavery and race relations. “This is not just a story of Black and white,” she says. “It’s the story of those groups but also Tejanos, Hispanics, and Native Americans.” She hopes “On Juneteenth” will cause readers to reflect on the complex nature of life — and of love. As awful as some periods of its history may be, she says, Texas is the place she and generations of her family have called home; recently, she found her great-great-grandfather’s voting registration card, dated 1867. “We tend to set a binary response to loving or hating a person or a place. But in every chapter of the book, there are good and bad things happening at the same time,” says Gordon-Reed, who hopes to devote more time to exploring her own family’s roots. “There’s a complexity of emotion there, a response that is both rational and irrational.”