By her 2L year, Regina Fitzpatrick ’08 was dead set on working for the U.N. on a peacekeeping mission. She’d come to HLS with a master’s in human rights after a stint with the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. The U.N.’s “legitimacy and access to hot spots,” she says, made it her goal.

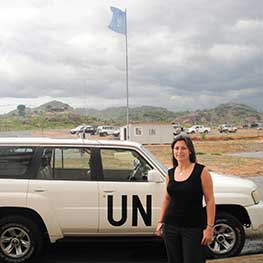

She is now working in Juba, South Sudan, living her dream.

Much credit, she says, goes to Alexa Shabecoff, head of the HLS Bernard Koteen Office of Public Interest Advising, who in fall 2010 called her attention to the U.N.’s National Competitive Recruitment Exam. “If you pass it and are placed in a post,” Fitzpatrick says, “you get a career contract, which is a bit like the Holy Grail within the U.N. system.”

At the time, she was in Sudan as the region prepared for the referendum on southern Sudan’s independence, which had been set in motion by a 2005 peace agreement to stop its civil war (one of Africa’s longest). Thanks to an HLS Human Rights Program Satter Fellowship (which Shabecoff had also alerted her to), Fitzpatrick worked for two NGOs providing legal analysis, first related to monitoring the referendum process, and then, after the vote in January 2011, focused on the transition to independence.

Fitzpatrick completed a comprehensive written exam and an oral exam and, 10 months later, learned that she’d passed the U.N.’s NCRE.

By then it was summer 2011 and South Sudan’s independence had just become official. Having relocated to Juba, the new country’s capital, Fitzpatrick began inquiring whether there might be a position for her in the brand-new U.N. peacekeeping mission. It turned out the lawyer in charge of setting up the rule of law component of the mission was also an HLS alum, David Marshall LL.M. ’02, whom Fitzpatrick had met during law school through her work with OPIA.

“He was a wonderful advocate,” she says. Within three weeks she had an offer.

She is now a judicial affairs officer in the Rule of Law and Security Institutions Support Office. As part of the mission’s mandate, her office focuses on helping the new state to develop the legal institutions to end prolonged, arbitrary detention. In South Sudan, a large number of detainees are held without charges, on remand pretrial or past the end of their sentences. Fitzpatrick has been working with government officials, judges and prosecutors as well as police and prison staff to assess the problem and work on recommendations for reforms.

In December and January, large-scale intertribal killings took place in South Sudan’s Jonglei State. Fitzpatrick has assisted the mission’s Human Rights Division, interviewing survivors to investigate the attacks. It’s part of her office’s efforts to advise the government on how to respond—work that is ongoing, she says, as the region is now engaged in a civilian disarmament campaign and local peace processes.

By midspring, incidents of cross-border violence had broken out between South Sudan and Sudan over oil-rich territory, and tensions continue to escalate. Fitzpatrick says the situation makes her office’s work more challenging, but its efforts continue.

After almost two years in the region, Fitzpatrick sometimes considers other hot spots she could work in, such as Libya and Syria. For her, these places don’t signify danger, but the potential to protect human rights and help countries rebuild—one of the best features of a career in the U.N., she says. “I’m excited about all of the possibilities.”