A half century after it was written, a letter to the Bulletin is finally published

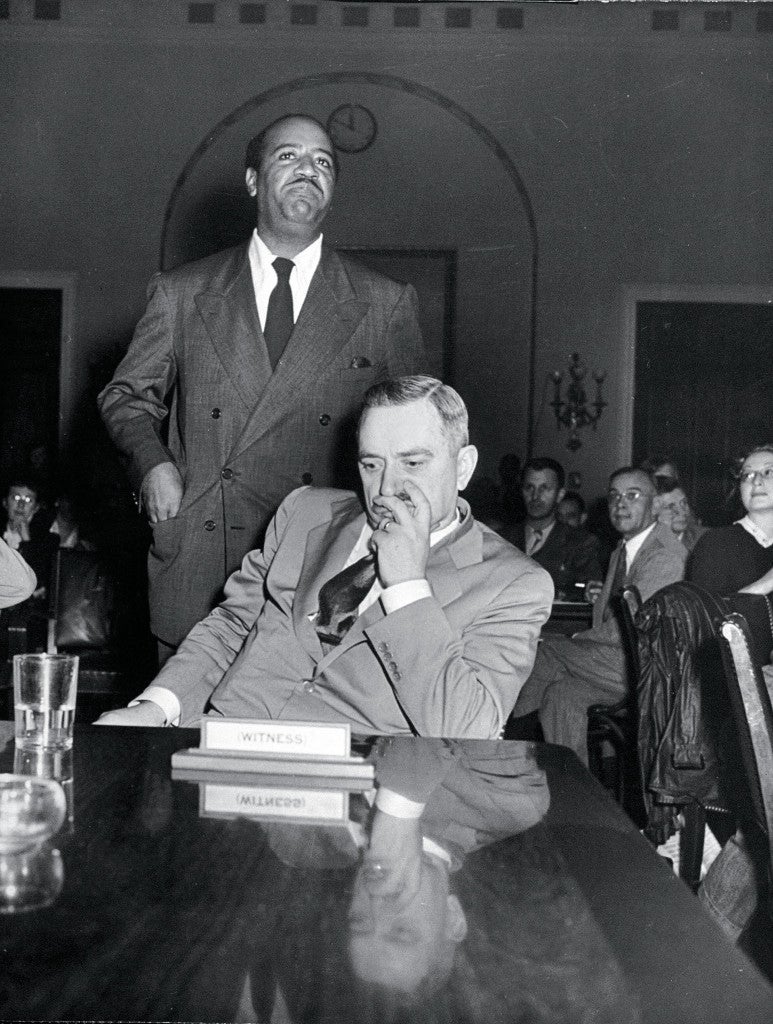

Benjamin Davis (standing) and Earl Browder, general secretary of the American Communist Party, preparing to testify in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee.

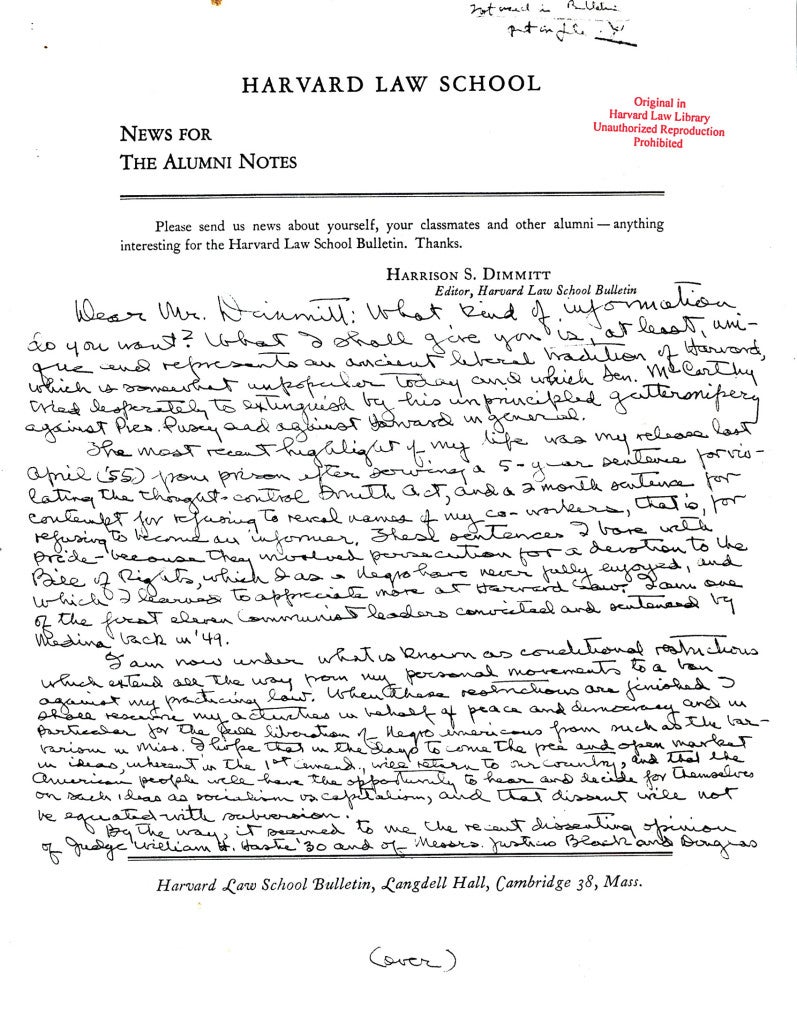

In the 1950s, the HLS Bulletin asked for alumni updates just as it does today. “Please send us news about yourself, your classmates and other alumni—anything interesting for the Harvard Law School Bulletin,” read the form from Harrison S. Dimmitt ’25, the Bulletin editor.

Among those who replied was Benjamin J. Davis ’28, a leading figure in the American Communist Party, who was also a civil rights attorney and a former New York city councilman. The first black Communist ever to be elected to office in the U.S., he worked to bring national attention to lynchings and Jim Crow laws. Davis joined the Communist Party shortly after law school, while he was defending a young black Communist labor organizer who had been sentenced to 20 years under a slave insurrection statute. At the height of the Cold War, Davis was a trenchant critic of the U.S. government.

Davis and Robert Thompson outside the federal courthouse in New York City during their trial. After they and the other defendants were sentenced under the Smith Act, demonstrations broke out in Harlem.

When Davis replied to the Bulletin, he had plenty of news: He had just been released from federal prison the year before, in April 1955, after being charged, tried and incarcerated under the notorious Smith Act, for alleged subversive activities. Not long afterward, he was charged again—this time under the McCarran Act, which carried a possible sentence of 30 years in prison—for his refusal to register as an agent of the Soviet Union. In 1962, with the charges still pending, Davis returned to HLS to speak on a panel with Dean Erwin Griswold LL.B. ’28 S.J.D. ’29. Davis died two years later, at the age of 6o. The letter to the Bulletin, excerpted here, was discovered by historian Clarissa Atkinson this spring in the Harvard Law School archives. At the top is a handwritten note: “Not used in Bulletin. Put in file.”

Dear Mr. Dimmitt:

What kind of information do you want?…

The most recent highlight of my life was my release last April (’55) from prison after serving a 5-year sentence for violating the thought-control Smith Act, and a 2-month sentence for contempt for refusing to reveal names of my co-workers, that is, for refusing to become an informer. These sentences I bore with pride—because they involved persecution for a devotion to the Bill of Rights, which I as a Negro have never fully enjoyed, and which I learned to appreciate more at Harvard Law. I am one of the first eleven Communist leaders convicted and sentenced by [Judge Harold] Medina back in ’49.

I am now under what is known as conditional restrictions which extend all the way from my personal movements to a ban against my practicing law. When those restrictions are finished I shall resume my activities in behalf of peace and democracy and in particular for the full liberation of Negro Americans from such as the barbarism in Miss. I hope that in the days to come the free and open market in ideas, inherent in the 1st amend., will return to our country, and that the American people will have the opportunity to hear and decide for themselves on such ideas as socialism vs. capitalism, and that dissent will not be equated with subversion.

By the way, it seemed to me the recent dissenting opinion of Judge William H. Hastie ’30 and of Messrs. Justices Black and Douglas on Smith Act cases, are far more in line with the best of Harvard Law than those of Mr. Justice Frankfurter [LL.B. ’06] or even of Justice Learned Hand [LL.B. 1896]—the latter two seemed to have been caught up in the hysteria and fears of the moment, without their having the foresight to see that these fears are purely transitory. I have abounding faith in the good sense of the American people, and that the sanity, identified with the best of Harvard, to which I’m indebted, will replace the witch-hunting insanities of the present day. There are already signs that this process is beginning.

Davis and Robert Thompson outside the federal courthouse in New York City during their trial. After they and the other defendants were sentenced under the Smith Act, demonstrations broke out in Harlem.

I know little of my classmates—and I presume none of them—or few of them—would touch me, so to speak, with a 10-ft. pole, not even as my attorney through this period. This too is a very practical matter, since I’m still under a ’48 indictment for membership in the Communist Party (the sentence I served was for conspiracy to teach and advocate the violent overthrow etc.), which is, in principle, double jeopardy if ever there was such a thing. I often wonder if any of my classmates or other alumni would be bold enough to represent me! That’s a good project for interested Bulletin readers. I am interested in hearing and reading of Law alumni, particularly of my classmates, and don’t despair of them, even if they despair of me. For example I’d like to see William H. Jackson ’28 make a lot of progress in removing barriers to closer East-west contacts between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. …

I’m not in a position to contribute at this time to such publications as the Bulletin. (I haven’t been able to find an employer daring enough to hire me.) But I’d appreciate continuing to receive such publications, in the understanding that I’ll contribute when I’m gainfully employed.

Ben J. Davis

1 W. 126 St., NYC