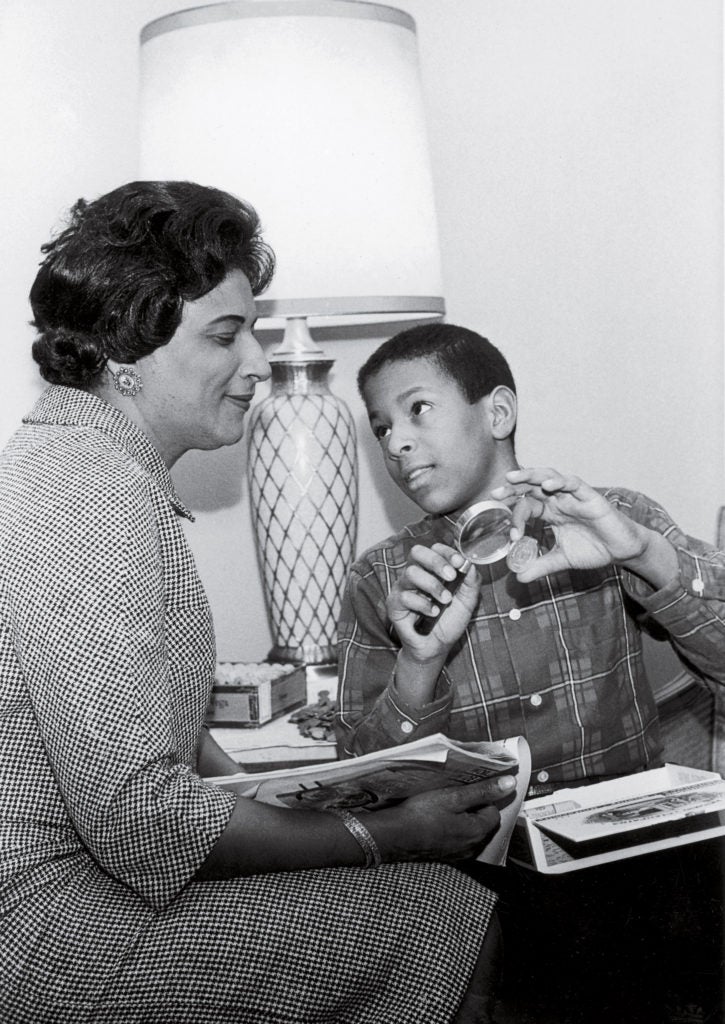

Even when he was 5, Joel Motley III knew his mother was doing important work. He’d see her on the national news and kiss the TV.

His mother, Constance Baker Motley, a lawyer for the NAACP’s legal defense fund, was traveling across the South, challenging segregated schools. As Motley grew up, he watched his mother win historic victories for black students, from the Little Rock Nine to James Meredith in Mississippi. As a little boy, he even came along while she was working on Meredith’s case and stayed in the home of Medgar Evers, the field secretary of the NAACP in the state. Motley saw her go on to become the first black female Manhattan borough president, New York state senator, and federal judge.

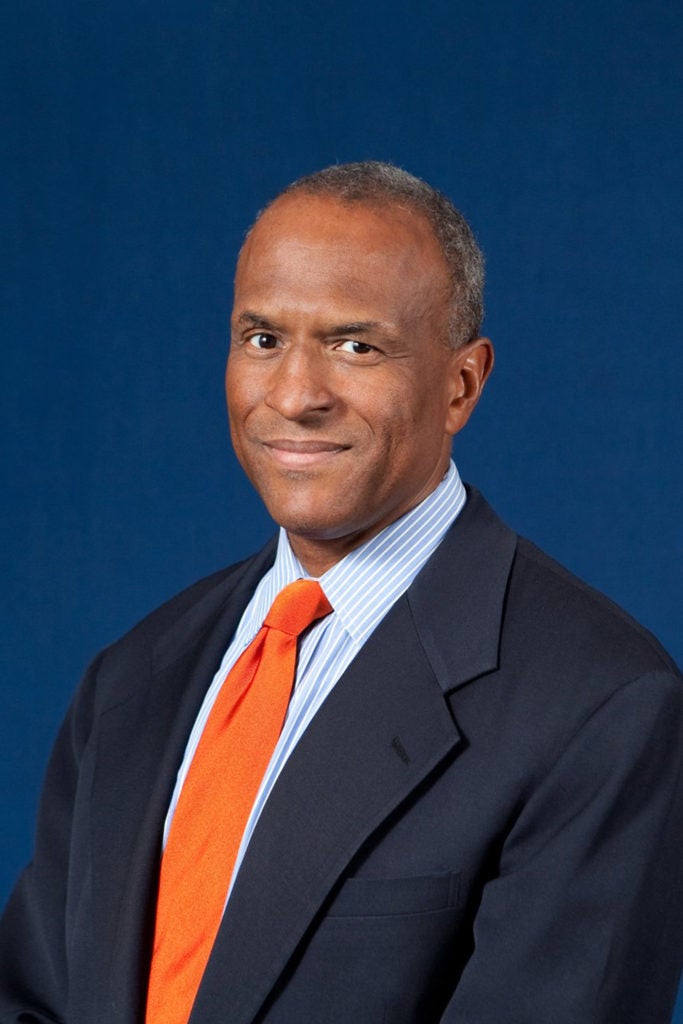

Now, Motley ’78 has co-produced a short film about his late mother, “The Trials of Constance Baker Motley,” which screened at HLS this fall.

“When I was eight or nine, I was walking with my mother in Harlem, on Amsterdam and 125th,” he recalls. He told his mother he wanted to be a policeman or a fireman so that he could help people. “Lawyers can help people,” she replied. “If someone is injured on the job and can’t make any money, a lawyer can represent them and get them enough money to help pay the rent.”

That thought led Motley to HLS, then to work as an aide for U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan in the 1980s. He’s now an investment banker, providing advice on capital markets to developing countries. He’s also co-chair of the board of Human Rights Watch, fulfilling a longtime goal of doing work similar to his mother’s.

Motley’s documentary traces his mother’s life from her childhood in Connecticut through her nearly 20 years as a civil-rights lawyer. Co-produced with Motley’s neighbor, filmmaker Rick Rodgers, it debuted last year at the Tribeca Film Festival and won the audience award for best documentary short at the Austin Film Festival. It intersperses news footage with Motley’s interviews with his mother’s former clients, shot by Rodgers in a stark, shadowy black and white that evokes the menace of the Jim Crow South. The interviewees include James Meredith, Harvey Gantt, and Charlayne Hunter-Gault, the first black students to attend the University of Mississippi, Clemson University, and the University of Georgia, respectively.

“The interview with Charlayne is the one that always brings tears to my eyes, every time I watch it,” Motley says. Hunter-Gault, now a retired broadcaster, recalls a time when Motley’s mother opened up to her, saying she wanted to be home with her son and husband, but had a job to do: getting Hunter-Gault into school in Georgia. “She captures the whole work-life balance my mother had to navigate,” Motley says. His mother never spoke of that tension with him, but “I picked it up intuitively,” he adds.

Motley has showed the documentary to a gathering of black and Hispanic federal judges, including U.S. Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor. He was surprised to meet a black, female federal judge who didn’t know his trailblazing mother’s name. “The sands of time can take anyone out,” says Motley, who speaks with a languid refinement that hints at his education: Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard College, followed by HLS.

He’s given several interviews to HLS professor Tomiko Brown-Nagin, who’s writing a biography, “Constance Baker Motley: The Honor and Burden of Being First.”

“She was a very dignified person,” Brown-Nagin says. “There seems to be something of the mother in the son, in the way he carries himself. In getting to know him, one is also getting to know the mother and her values, and her strong sense of history.”

By making the film, Motley fulfilled a long-suppressed personal dream. Inspired by an HLS grad he met who’d become a movie producer, Motley told his parents on the night of his law-school graduation that he’d like to do the same. “They both just burst out laughing,” he says. “But it was nervous laughter, because it sounded so crazy. They thought I couldn’t be serious. I wasn’t serious enough to overcome this derision, so I set my dream aside.”

Then in 2010, during a party at Motley’s home, Rodgers, a neighbor of his in Westchester County, New York, saw a photograph of Motley’s mother with President Lyndon B. Johnson, from the day he nominated her to be the nation’s first black female federal judge. Impressed by her career, Rodgers suggested that he and Motley collaborate on a film about her.

Motley thought he knew his mother’s story, but he came to new insight into her life by making the film. Listening to recordings of his mother being interviewed for a Columbia University oral history, Motley reached a deeper understanding of her decision to turn her career toward politics in New York after Evers was murdered in Mississippi just outside his home. “Looking back, I now realize that she thought, ‘If it’s that dangerous, where I could’ve been killed, my son could’ve been killed, maybe I need to start thinking about doing something else.’”

It was eerie to listen to his mother’s voice again. “Ten, 12, 14 hours of her telling her story, and it’s clear as day,” Motley says. “And when I started listening to [the recordings], she was dead five years already. And you listen to it, and it’s so clear, you think, ‘Why can’t I just call her on the phone?’”