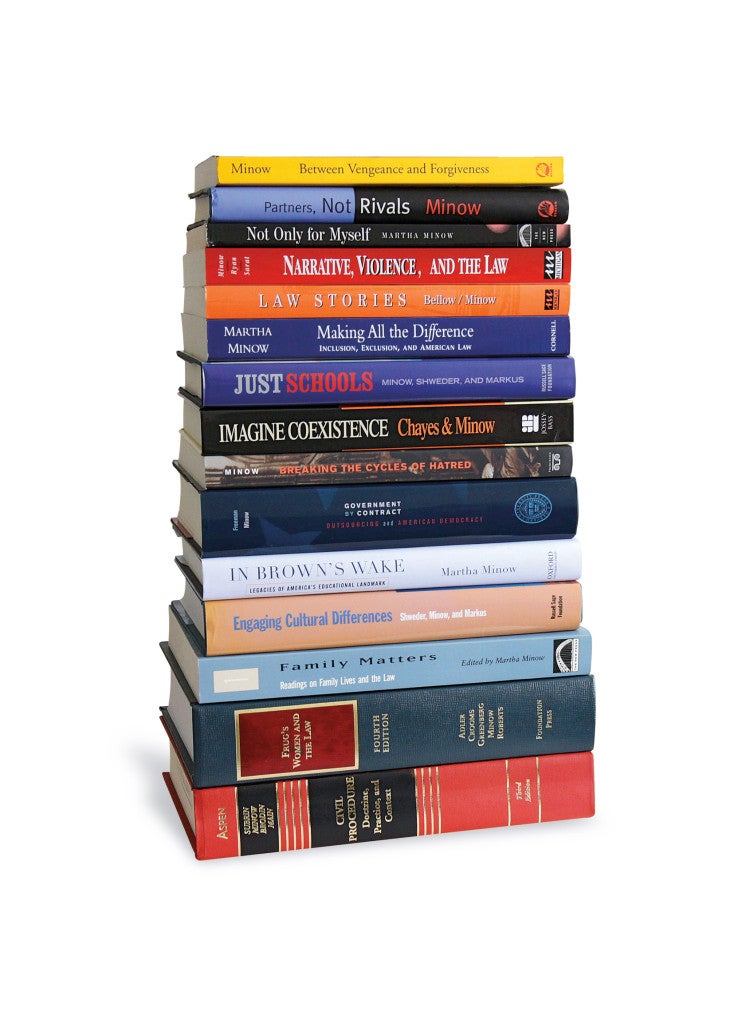

Her many articles and books explore topics such as privatization, family law, responses to mass violence, civil procedure, equality and inequality, and religion and pluralism.

Excerpts from just a few of her publications follow. (See her bibliography for more.)

When the Power of the Collective Is Replaced with Cash

“Military lawyers have worried for a decade about what law applies to contractors working in military settings. Even with the recent legal changes, contract employees are not governed by unit discipline; unlike government actors, they are not regulated by civilian statutes such as the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). Ambiguities remain over what law applies if contract employees are captured or injured by the enemy, and whether they have the legal authority or actual competence to defend themselves with force. Nor is it clear whether they are liable under American tort law for conduct occurring abroad. …

“Even if the lines of authority clearly locate the civilian contractor employees under military command, these civilians do not face the same rewards and sanctions as do the members of the military, including military culture and command structure.

“As one former soldier working in private security in Iraq wrote in a note to a reporter, ‘Being motivated, and also somehow restrained, by the trappings of history, and by being part of something large, collective, and, one hopes, right’ characterizes the military experience, but ‘being a security contractor strips much of this sociological and political upholstery away, and replaces it with cash.’”

From “Outsourcing Power: Privatizing Military Efforts and the Risk to Accountability, Professionalism, and Democracy” in “Government by Contract: Outsourcing and American Democracy” (edited with Jody Freeman LL.M. ’91 S.J.D. ’95, Harvard University Press, 2009)

The Institutions We Create Shape our Needs and Beliefs

“Contemporary responses to mass atrocities lurch among the rhetorics of law (punishment, compensation, deterrence); history (truth); theology (forgiveness); therapy (healing); art (commemoration and disturbance); and education (learning lessons). None is adequate and yet, by invoking any of these rhetorics, people wager that social responses can alter the emotional experiences of individuals and societies living after mass violence. Perhaps, rather than seeking revenge, people can rebuild.

“As public instruments shaping public and private lives, legal institutions affect the production of collective memories for a community or nation. Social and political decisions determine what gives rise to a legal claim. Not only do these decisions express views about what is fair and right for individuals; they also communicate narratives and values across broad audiences. Whose memories deserve the public stage of an open trial, a broadcast truth commission, or a reparations debate? What version of the past can acknowledge the wrongness of what happened without giving comfort to new propaganda about intergroup hatreds?

“Research across a wide range of academic disciplines has produced a new consensus about human memory. It turns out that recollections are not retrieved, like intact computer files, but instead are always constructed by combining bits of information selected and arranged in light of prior narratives and current expectations, needs, and beliefs. Thus, the histories we tell and the institutions we make create the narratives and enact the expectations, needs, and beliefs of a time.”

From “Breaking the Cycles of Hatred: Memory, Law, and Repair.” Introduction, with Commentaries, in “Breaking the Cycles of Hatred: Memory, Law, and Repair” (Nancy L. Rosenblum ed., Princeton University Press, 2002)

Peremptory Challenges Preclude Empathizing Across Difference

“Eliminating peremptory challenges would reduce the parties’ (and lawyers’) abilities to shape the jury and seek to influence their results, which could both help but also significantly hurt members of disadvantaged groups. The very practice of trying to shape the jury through peremptory challenges has been deeply characterized by stereotypic predictions about how members of particular groups would respond to the topics on trial. Ending the peremptory challenge would, at least symbolically, rule all such thinking out of bounds, at least in this setting.

“Indeed, parties, and lawyers, commonly seek to remove jurors based on their group characteristics because they load many presumptions—and prejudices—onto those identities. The prosecution tries to exclude people who look like the defendant on the assumption of undue sympathy; the defense tries to exclude those whose racial and ethnic membership differs from that of the defendant. Why permit peremptory challenges that presume that people cannot empathize across lines of difference? Not only is such a rule untrue to human possibilities, it might also be a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

From “Not Only for Myself: Identity, Politics, and the Law” (The New Press, 1997)

The History of Family Law Revisited

“This examination has surfaced some of these conclusions that contrast with the traditional depiction of family law’s history: 1) families in colonial society were not as patriarchal, and women were not as dependent, as the traditional story maintains; 2) some women in the 19th century who had opportunities to achieve autonomy through paid and volunteer work outside the home did not seek either independence or dependence, and hence do not fit the picture of relentlessly evolving individualism which is part of the traditional story; 3) the collective activities of women, in factories and in women’s associations, presented a counterpoint to the individualist conception of state-enforced rights that supposedly became a dominant feature of the late 19th and 20th century experience; and 4) women’s forays into the public worlds of work and political and moral reform engaged them in activities beyond their traditional family roles; and yet women often undertook these activities by reference to conceptions of themselves as wives and mothers, widows and daughters, with deliberate efforts to extend family-like relationships beyond the family itself.”

From “Forming Underneath Everything that Grows: Toward A History of Family Law,” 1985 Wisconsin Law Review 819 (1985)

Empathy and the Pain of Others

“Boundaries and categories of some form are inevitable. They are necessary to our efforts to organize perceptions and to form judgments. But boundaries are also points of connection. Categories are humanly made, and mutable. The differences we identify and emphasize are expressions of ourselves and our values. What we do with difference, and whether we acknowledge our own participation in the meanings of the differences we assign to others, are choices that remain. The experts in nineteenth-century anesthesiology did not stop to ask whether they properly understood the pain of others. We can do better. As Nancy Hartsock observes: ‘It is only through the variety of relations constructed by the plurality of beings that truth can be known and community constructed.’ Then we can constitute ourselves as members of conflicting communities with enough reciprocal regard to talk across differences. We engender mutual regard for pain we know and pain we do not understand.”

From “Making All the Difference: Inclusion, Exclusion, and American Law” (Cornell University Press, 1990)

Tolerance in an Age of Terror

“[A] review of contemporary scholarship and of news coverage reveals two narratives linking tolerance and terrorism. The first sees overreaction and intolerance as responses to terror; and the second sees under-reaction and too much tolerance. Law review articles and public interest advocates charge the United States since 9/11 with overreaction that jeopardizes legal and cultural commitments to tolerance. Recent books and articles allege under-reaction on the part of several European nations, citing an ideal of multicultural tolerance that offers space for intolerant and even murderous individuals and groups to plan and carry out violent acts. I will suggest, however, that a single nation may seem to or actually produce both intolerance and too much tolerance, generating both overreactions and under-reactions to terrorism. Because the United States and European nations each have pursued policies that threaten civil liberties and indicate intolerance of immigrants and dissenters, a detailed assessment is necessary—and so is analysis of the rhetorical arguments about overreaction and under-reaction. Moreover, tolerance can be a feature of personal ethics, or national character, or public policy, and the connections between tolerance and anti-terrorism can take complex forms at each of these levels.”

From “Tolerance in an Age of Terror,” Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal, Vol. 16, No. 3 (2007)