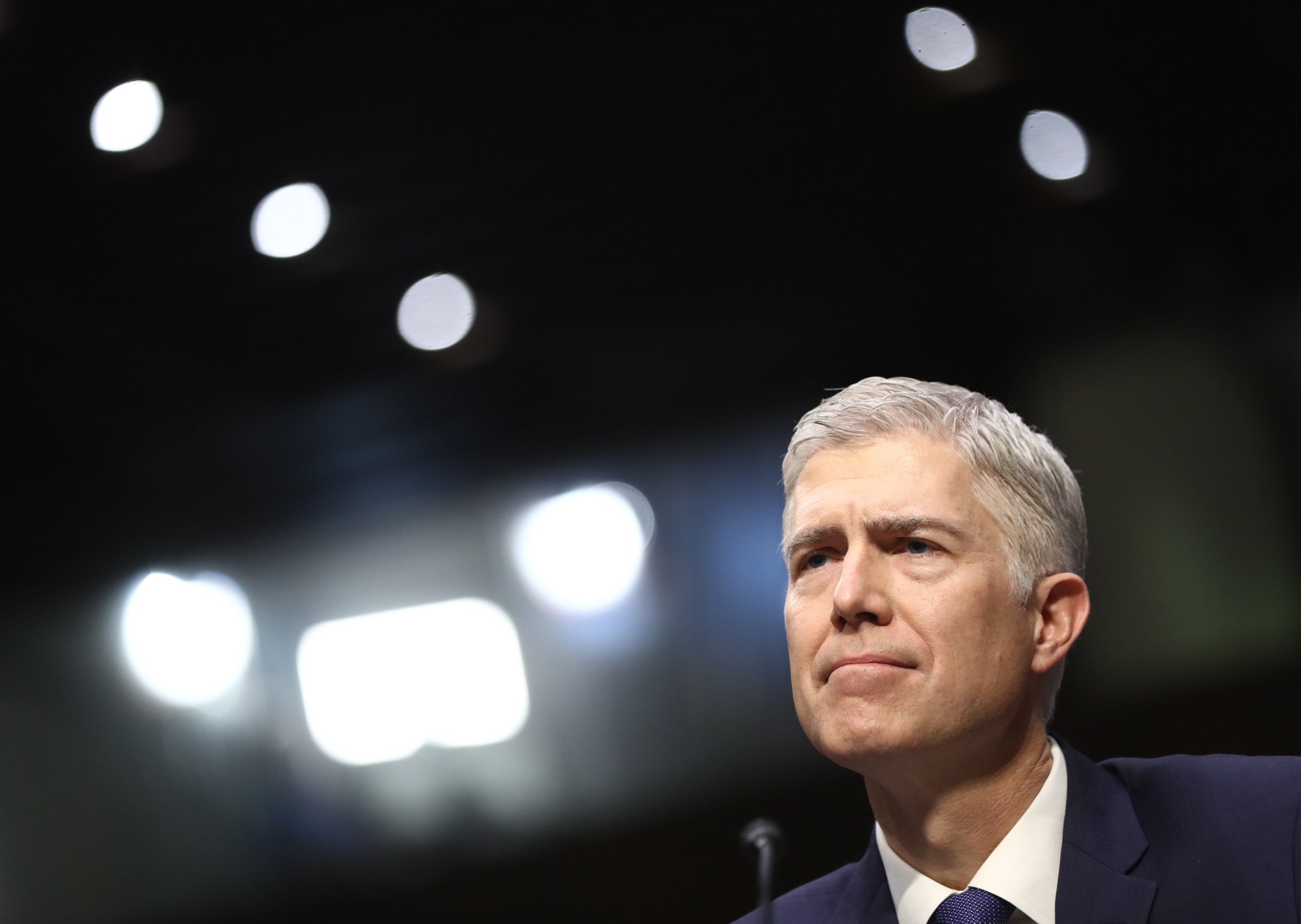

In a book featuring speeches and writings over the course of his 30 years in the law, Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch ’91 offers “personal reflections on our Constitution, its separation of powers, and some of the challenges we face in preserving and protecting our republic today.”

Justice Gorsuch’s “A Republic, If You Can Keep It” (written with Jane Nitze ’08 and David Feder ’14) stems from the months-long process leading up to his confirmation by the Senate in 2017. He writes that during the confirmation process he heard people speak about the law and his time in the profession in ways he didn’t recognize: The notion of judges allowing policy preferences to affect their rulings was “foreign to my experience in the law,” he writes. The judges he most admires recognize that “the judge’s job is only to apply the law’s terms as faithfully as possible.”

“As the [confirmation] process unfolded, I came to worry that our civic understanding about these things—about the Constitution and the proper role of the judge under it—may be slipping away,” he writes.

Justice Gorsuch shares his thinking behind some of his own judicial decisions, such as one in which he considered whether the government could collect cellphone location data in light of the original meaning of the Fourth Amendment. In another case, he sheds light on a decision by diagramming a sentence from a statute about using a gun to commit a crime of violence or drug trafficking. Justice Gorsuch also explains his dissent when he was on the 10th Circuit in a case in which a seventh grader was arrested after disrupting a gym class with fake belches. Though the majority concluded that the law allowed for the arrest, however misguided it may have been, he cited appeals court precedent that a more substantial disruption of the school operations was required to justify the police response.

He highlights several cases to demonstrate the value of the framers’ decision to divide the powers of the federal government, which he calls “one of their most important contributions to human liberty.” When that separation is ignored, he writes, the rule of law is undermined and real people can get hurt, such as in the case of an immigrant married to a U.S. citizen who faced conflicting edicts from the executive and judiciary branches related to whether he needed to leave the country for 10 years in order to apply for lawful U.S. residency.

In other chapters, Justice Gorsuch explores how to improve access to affordable justice, including lowering the cost of legal education and easing prohibitions for nonlawyers to assist in legal matters. Writing on “ethics and the good life,” he offers a tribute to his former colleague Justice Anthony Kennedy ’61 and recommends to law school graduates 10 things to do in their first 10 years after graduation (find a passion outside the law is one).

In addition, he reveals how he was inspired by the man he would replace on the Supreme Court, Justice Antonin Scalia ’60, who died in 2016. While Justice Gorsuch was a student at HLS, he writes, the prevailing sentiment was that judges should turn to legislative history in order to discern the law’s purpose and that the Constitution was a “living document.” Justice Scalia visited the school to deliver a lecture “suffused with the conviction that when charged with interpreting congressional statutes and constitutional texts, judges should follow the law as written and originally understood. … ” The lecture was “a breath of fresh air,” Justice Gorsuch writes, and it would help lead him to embrace Justice Scalia’s judicial philosophy, which, he contends, is “how many of the founders conceived of the judge’s job when they wrote the Constitution.” Justice Gorsuch himself would go on to deliver his own lectures making the case for originalism and textualism, two of which are printed in the book.

While the book doesn’t focus on his Supreme Court nomination process, Justice Gorsuch does detail personal reflections from that time: the support he received from those who served as his law clerks, a young child who asked to hold his hand during turbulence on a flight to Washington, a stranger who saw him on television and sent him new socks because his appeared to be worn out. And in another personal touch, he writes about his family, including his grandparents, “who did as much to shape me as anyone,” and his mother, whom he calls a feminist before feminism.