Harvard Law School students help transform communities and the law every day by supporting people and organizations in need of legal assistance.

A pioneer in the development of experiential clinical education, Harvard Law School offers students hands-on training in a wide range of legal fields, from human rights, immigration, health, and housing law to cyber, tax, and veterans’ law. They do this by serving clients who might otherwise be unable to afford a lawyer.

Through 47 legal clinics and student practice organizations, Harvard Law students — more than 80 percent of whom participate in at least one law school clinic — provide hundreds of thousands of hours of free legal services to clients across the country and the world each year.

For one day in the 2019–2020 academic year, we followed just a handful of these clinics to see their work — and their efforts to advance justice — in action. Here is a look at that day, starting at 5:00 a.m. in Geneva, Switzerland and ending at 11 p.m. on the Harvard Law campus.

5:00 a.m.: Advocating for disarmament

Genève Aéroport, Geneva

It’s 5 a.m. at the airport in Geneva, and Bonnie Docherty ’01, associate director of Armed Conflict and Civilian Protection in the International Human Rights Clinic, is awaiting a flight back to Boston. Docherty and two students, Alev Erhan ’21 and Shaiba Rather ’21, have spent the past week at the United Nations at a meeting about the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons.

Docherty — who previously served as a legal adviser to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons as part of its Nobel Peace Prize-winning work to create the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons — had come to Geneva to advocate for preempting future technologies known as “killer robots” and for strengthening the current treaty on incendiary weapons, by fixing loopholes and providing better protections for civilians.

“These future technologies which are rapidly moving toward development have been called the third revolution of warfare, after gunpowder and nuclear weapons. They would select and engage, choose and fire on a target without meaningful human control,” said Docherty. “We’re working with civil society to preempt these weapons. This week we released a report on the proposed elements of a new treaty, and it was very well received by governments.”

While Docherty and her students faced some obstacles (Russia blocked consensus to continue discussions on amending the incendiary weapons treaty), she says overall the meeting was a success, with the vast majority of states calling for further discussions and condemning the recent use of incendiary weapons in Syria.

8:30 a.m.: Holding schools accountable

Children’s Law Center of Massachusetts, Lynn

Months of trying to advocate for educational support for her young son with special needs left Margarita Aguilar feeling “run over.”

“It was hard as a parent to keep pursuing his school because they didn’t see nothing legal behind me,” she said. Instead of getting the one-on-one support and assistance outside of the classroom that was mandated by his individualized education program, her son was sent home from school on a regular basis for acting out in the classroom.

Mikayla Harvey ’21, a student in HLS’s Child Advocacy Clinic, took on Aguilar’s son’s case as part of her clinical placement with the Children’s Law Center of Massachusetts. The center helps connect families of at-risk children with attorneys. Working closely with her client and the school administration, Harvey helped implement a new individually-tailored plan that strengthened educational support. In this morning’s meeting, Harvey announced that she just got word that the school has agreed to provide door-to-door transportation for Aguilar’s son.

Harvey, who chose to attend law school after volunteering with an organization that advocates for children in the foster care system, says she has learned first- hand how often children’s rights are ignored.

“A lot of times, schools aren’t willing to provide services, regardless of what the law says,” she said. For Harvey, advocating for children’s educational rights is a chance to be creative. She hopes the solutions she proposes will help her clients as well as other children and families facing similar educational challenges.

10:30 a.m.: Focusing on capital punishment

Langdell North, Harvard Law School, Cambridge

As dozens of students watch, Erin Fowler ’20 plays an attorney in a criminal case in which capital punishment is a possible penalty, questioning a potential juror who has expressed scruples about imposing the death penalty.

Questions asked by Fowler and her classmates ranged from “What if the victim were your own young son — would you still have trouble imposing the death penalty?” to “Do you believe in the importance of the law, and could you follow the judge’s instructions to apply it?”

Today’s exercise is part of Capital Punishment in America, a course designed by Professor Carol Steiker ’86 and aimed to help students consider the legal, political, and social implications of the practice of capital punishment in the United States — the only Western democracy that still imposes the death penalty. Steiker has focused extensively on the topic for much of her career and is co-author of “Courting Death,” which has been called “the most important book about the death penalty in the United States … because of its potential to change how the country thinks about capital punishment.” Earlier in the class she led students in a discussion of recent Supreme Court decisions that have shaped the practice of jury selection in capital cases over the past half-century and outlined a range of strategies employed by attorneys for the defense and the prosecution at this phase of a trial — in particular — attempts to “life-qualify” or “death-qualify” the jury.

This spring, some of the students will take these lessons with them as they work for clients on death row with organizations ranging from the Capital Habeas Unit in the Western District of Missouri to the Capital Post-Conviction Project of Louisiana to the Southern Center for Human Rights as part of the Harvard Law School Capital Punishment Clinic created and led by Steiker.

“The clinical placements, which are on site in capital defense offices around the country during the January term and continued remotely from Cambridge during the spring term, expose students to cutting-edge issues in capital litigation and to the challenges of working on life-and-death matters for actual clients,” said Steiker. “Many find this experience to be life-changing, both intellectually and emotionally.”

11:00 a.m.: A view from the bench

U.S. District Court, Boston

As a judicial intern at the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts, Caitlin Hoeberlein ’20 has a front-row seat to what goes on in the courtroom and the judge’s chambers.

Hoeberlein, who spent last fall interning at the Securities and Exchange Commission, decided she wanted a clinical placement that would put her “behind the bench a little bit more than in the back of the courtroom.” HLS’s clinical program helped her to design an independent clinical placement with Judge F. Dennis Saylor IV ’81 at the District Court. She spends her days attending hearings and trials, writing bench memos or summaries of what the judge will hear the next day, and helping to draft substantive opinions.

For Hoeberlein, getting the judge’s feedback has been incredibly helpful and important to her own writing.

“I get to learn firsthand what works, what doesn’t work. I will also hear the judge’s opinion about what was effective to him and what wasn’t,” she said. “On a very practical level, I’m learning how to act in a courtroom.”

12:00 p.m.: Fighting for animal rights

1607 Massachusetts Ave., Harvard Law School, Cambridge

Animal protection, one of the fastest developing areas of public interest law, is the focus of the Animal Law & Policy Clinic. Today, the inaugural group of students at one of Harvard Law School’s newest clinics meets with Visiting Assistant Clinical Professor and Clinic Director Katherine Meyer, one of the most experienced animal protection litigators in the country; Clinical Instructor Nicole Negowetti; and Chris Green ’04, executive director of the Animal Law & Policy Program, to discuss this semester’s advocacy efforts.

In October, two of the clinic’s students traveled to Washington, D.C., to testify at a hearing held by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on “Horizontal Approaches to Food Standards of Identity Modernization.” The clinic closely monitors technological and regulatory developments within the food sector that have the potential to affect animals, including plant-based and cell-based alternatives to animal food products.

12:30 p.m.: Holding former heads of state accountable

11th Circuit Court of Appeals, Miami

For more than a decade, Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic has been pursuing justice for indigenous people killed during “Black October” 2003, when the Bolivian government violently repressed a popular protest against government policies. In 2008, IHRC partnered with the Center for Constitutional Rights and Akin Gump to file Mamani et al. v. Sánchez de Lozada and Sánchez Berzaín, a lawsuit brought under the Torture Victim Protection Act against Bolivia’s former president and minister of defense for their roles overseeing the Bolivian security forces’ lethal use of force against unarmed civilians.

When the case went to trial in Federal District Court in Florida in 2018, it had already made history: It was the first time a living former head of state faced his accusers in a human rights case in U.S. court. On April 3, 2018, in a landmark decision, a unanimous jury found the former Bolivian leaders liable for the extrajudicial killings of eight indigenous people — and awarded the plaintiffs $10 million in damages.

“Frankly, it’s groundbreaking,” said Thomas Becker ’08, a clinical instructor at the International Human Rights Clinic who, with Susan Farbstein ’04 and Tyler Giannini, co-directors of the clinic, has been involved with the case since its inception. “It’s the first time in history that a living former president is forced to answer for his human rights violations in a U.S. Court. It’s a game-changer for human rights and accountability.”

But just weeks later, on May 30, 2018, the judge cited insufficient evidence to support the jury’s determination and overturned the verdict.

Today, Becker is among a large team of IHRC students, alumni, faculty, staff and their law firm partners, who are back in Florida to appeal the trial court’s decision. They are joined by two of the plaintiffs, Eloy and Etelvina Mamani, whose 8-year-old daughter, Marlene, was killed during Black October. In arguments before the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, the legal team is arguing that the judge’s decision should not stand and that the jury verdict should be reinstated.

2:00 p.m.: Defending the underserved

1607 Massachusetts Ave., Harvard Law School, Cambridge

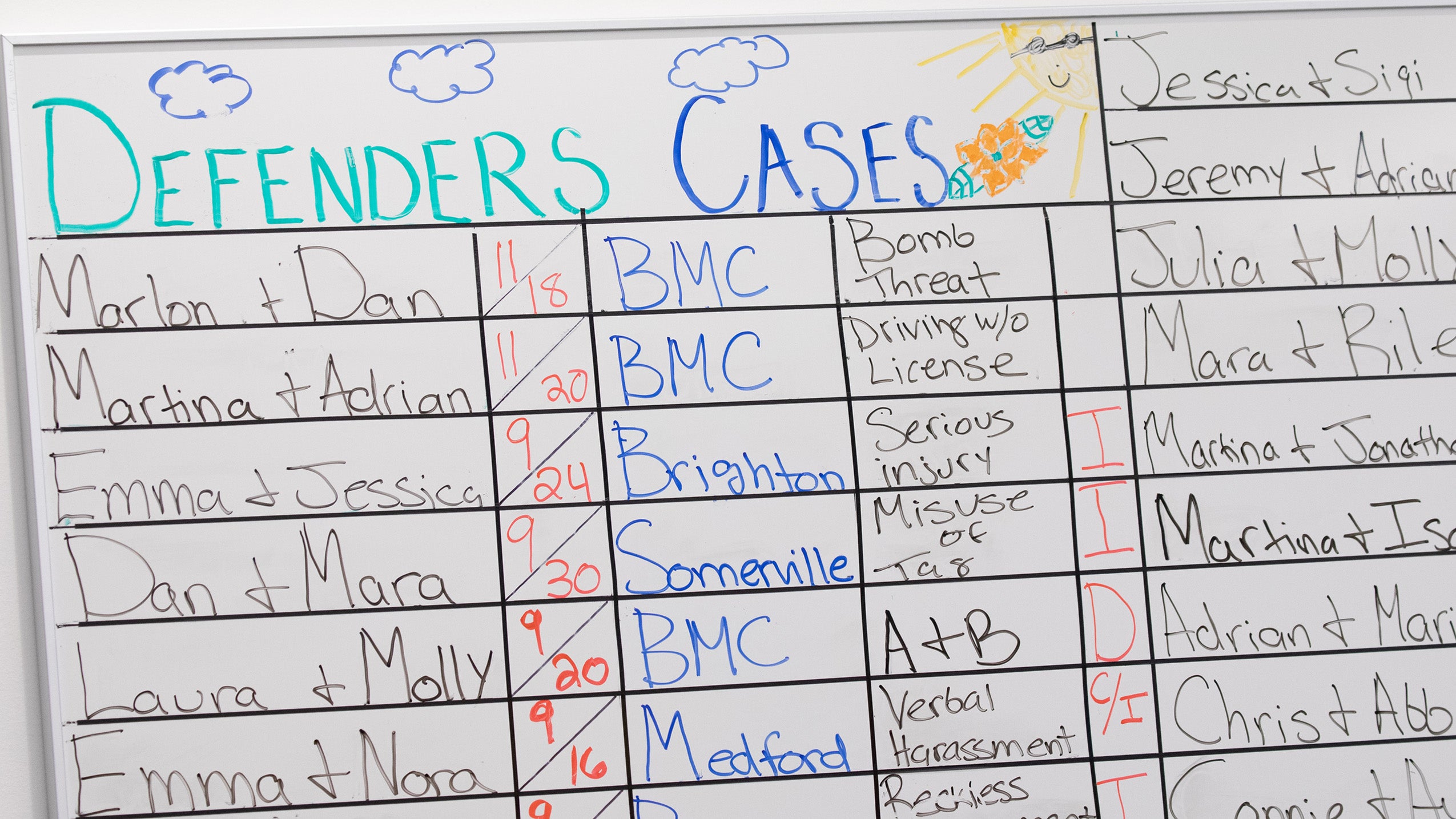

“The outcome of this hearing can determine whether or not someone has a criminal record or whether they are able to get these allegations dismissed entirely,” said Martina Tiku ’20, president of Harvard Defenders.

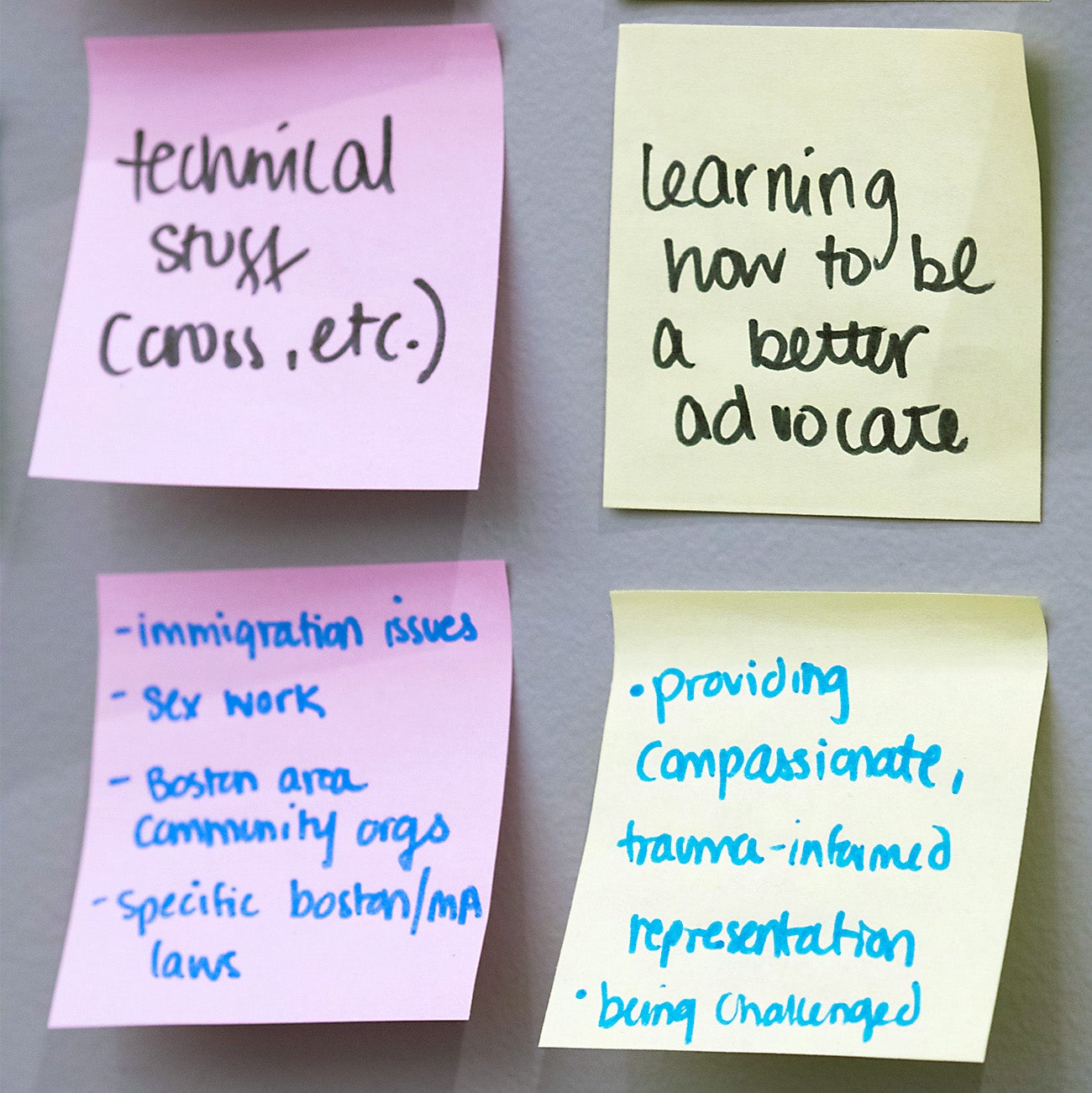

Defenders, the only legal services organization in Massachusetts that focuses exclusively on representing low-income defendants for free in criminal show-cause hearings, has assisted thousands of indigent people while offering students invaluable experience and exposure to the realities of the criminal justice system. Students meet weekly to discuss the arguments they plan to present at hearings and consider all the factors that might influence the magistrate’s decision.

At today’s team meeting, students share strategies for upcoming cases that touch on issues ranging from trespassing to driving with a suspended license, to possession of an illegal substance, to a client who made an illegal turn and was subsequently detained for being an undocumented immigrant. In Massachusetts, where there is no right to court-appointed counsel in these proceedings, representation by Defenders is one of the few options for those who can’t afford a private lawyer. Clients served by Defenders are charged with a range of offenses from nonviolent misdemeanors to violent felonies. They are often at risk of losing jobs, housing, their freedom, driver’s licenses and the ability to remain in the United States.

Tiku’s clients’ resilience and “grace and composure” in navigating a criminal legal system that is “stacked against them” humble her, she says, but they also motivate her to do her best in every interaction with them.

“I have a tremendous amount of respect for the people that we work with,” she said. “We gain the privilege of being able to work with these clients and get a window into their lives.”

4:00 p.m.: On call to combat housing insecurity

Wasserstein Hall, Harvard Law School, Cambridge

From the fifth floor of Wasserstein Hall, Dan Reis ’20, Rebecca Raftery ’21 and Alison Roberts ’22 are on the front lines of advocating for tenants, fielding calls from Boston-area residents seeking advice on landlord-tenant problems or eligibility for public housing. In a nearby office, Anna Jessurun ’22 meets with Clinical Instructor Shelley Barron to prepare for a Section 8 housing voucher termination case. As part of their pro bono work with Harvard Law School’s Tenant Advocacy Project, the students help city residents navigate the bureaucracy of public and subsidized housing.

Nearly 65% of Boston residents rent, rather than own, their homes. Shortages of affordable housing in the city mean that low-income residents, including those receiving federal assistance, struggle to find and afford homes, often paying a third or more of their income on rent.

By working with clients from the initial intake interview to representing them at trial-like administrative hearings before local housing authorities, Harvard Law students learn about the administration and funding details of subsidized housing programs in Massachusetts; the various obligations placed on housing agencies by federal and state laws; the agencies’ official and unspoken policies; and the rights and obligations of tenants.

Last year, TAP worked on more than 160 cases, providing representation to 76 clients who, with their families, were at risk of losing their affordable housing. For other clients, they provided detailed information and advice.

“I wanted to get experience doing direct service work as a first-year law student,” said Jessurun. “TAP was a perfect fit.”

4:00 p.m.: Shining a light in dark places

6 Everett Street, Harvard Law School, Cambridge

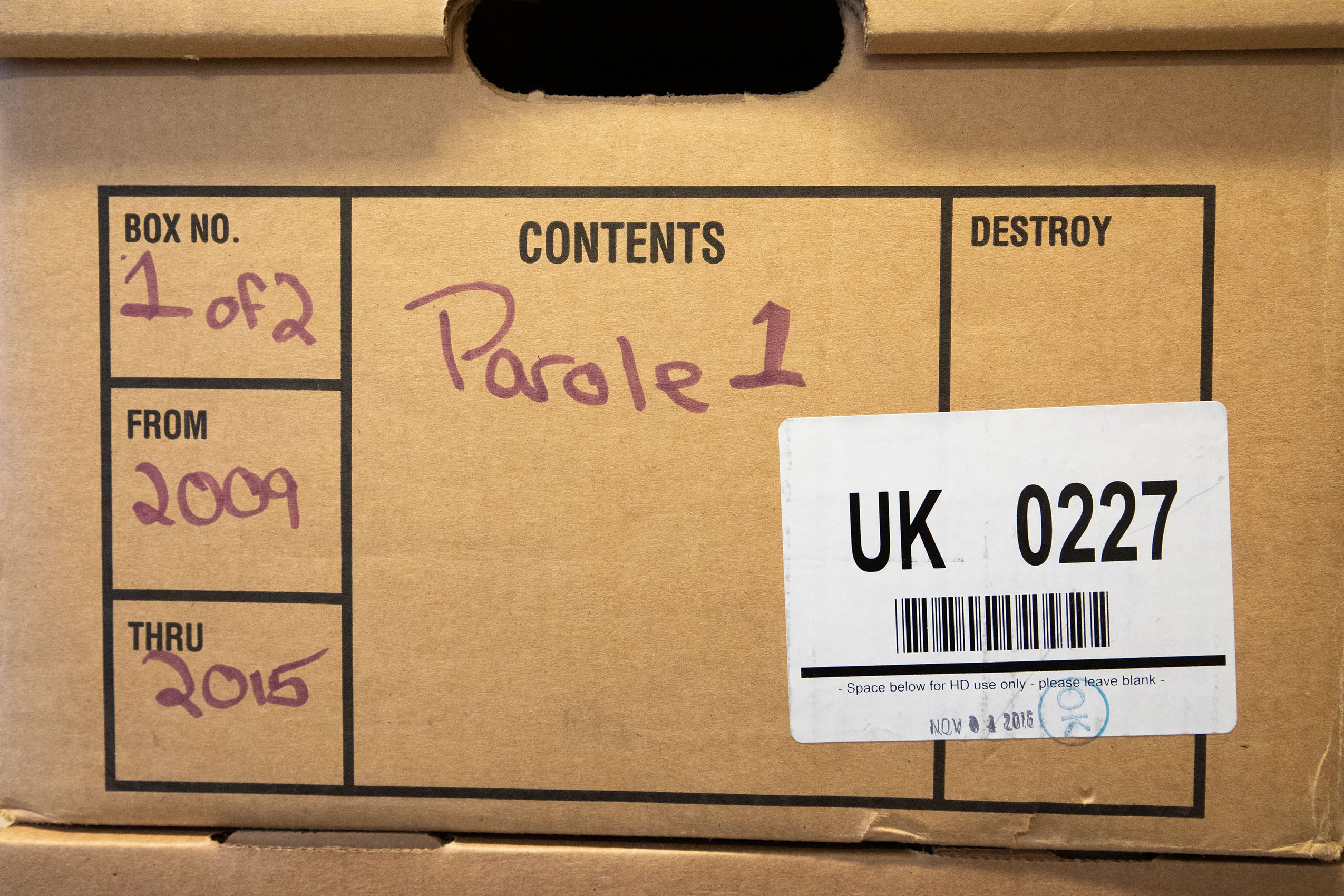

People incarcerated in Massachusetts prisons have no guarantee of counsel in parole and prison disciplinary hearings. Every year, students from the Harvard Law School Prison Legal Assistance Project assist thousands of prisoners, including providing direct representation in dozens of these hearings, while offering research assistance to hundreds of other prisoners.

PLAP, a student practice organization at HLS, gives students the chance to handle a case from beginning to end, with guidance from a supervising attorney. For disciplinary hearings, students meet with their clients in prison, request and review discovery, and defend their clients at a trial-type hearing, complete with the cross-examination of correctional officers and delivery of a closing argument. For parole hearings, students advocate for a prisoner’s liberty by gathering a broad array of information about the client’s family and personal life, prison record, and plans for reentry, and by preparing the client for intense questioning by the seven-member parole board.

This afternoon, as on most afternoons, PLAP’s office is filled with students fielding client calls and working on clients’ cases.

Those cases include disciplinary hearings alleging assault or other serious misconduct, for which the prison’s sanction can include up to ten years in solitary confinement. In several cases this year, PLAP students have successfully defended against such charges, obtaining not guilty findings or minimizing the sanctions to solitary time already served. Earlier this year PLAP built on a 2017 court victory by securing a new court order prohibiting the Parole Board from discriminating against prisoners with mental disabilities, in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

4:30 p.m.: ‘In the district attorney’s office, you never lose if justice is done’

Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office, Boston

“On the sixth day of my placement, they handed me a jury trial,” said Brooke Cohen ’20, a Harvard Law student in the Criminal Prosecution Clinic working in the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office.

Getting “proximate to the work” is the goal of clinical internships, says District Attorney Rachael Rollins, who offers opportunities in her office for students to handle everything from charging decisions, to arraignments or bail requests, to even handling a trial. “I want students to see the hard work that my staff, as well as my lawyers, are doing every day to help the municipal and district courts work.”

Every week, students meet over dinner with Clinical Instructor Jack Corrigan ’87, a former assistant district attorney, to process what happened in court that week, share issues they are wrestling with and discuss prosecutorial discretion. As part of her work at the Suffolk County DA’s office, Cohen prosecuted an individual charged with driving under the influence and participated in the jury selection, opening arguments, questioning of witnesses, and closing statements.

“I got a taste of the entirety of a trial from start to finish,” she said.

What seemed like an open-and-shut case when she first viewed the file became more complex as she dug into the facts of the case and circumstances of the defendant. “The blessing and the burden of being in a progressive prosecutor’s office is you have to pursue justice and pursue the law,” Cohen said, “but do it with an eye for empathy and awareness of what’s going on outside of the courtroom.”

As for her first trial, she said, “We didn’t win, but we didn’t lose. In the district attorney’s office, you never lose if justice is done.”

5:00 p.m.: Helping clients seal criminal records

WilmerHale Legal Services Center of Harvard Law School, Jamaica Plain

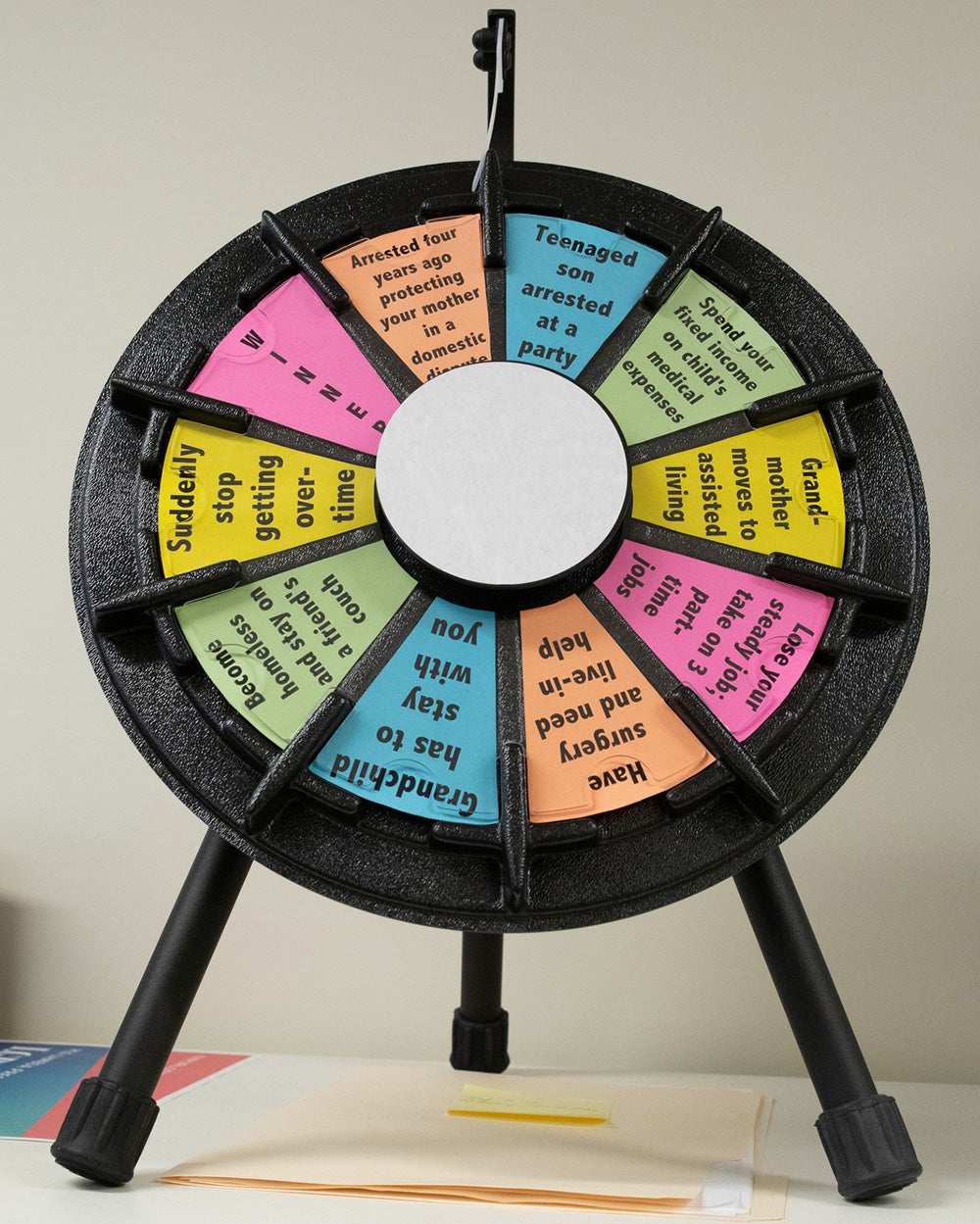

A mother of two is denied a job as an Uber driver and a Section 8 housing voucher because of her drug conviction as a teenager; a contractor with a past misdemeanor can’t enter federal buildings or work in any building leased to a federal agency; and an elderly homeless veteran and recovered alcoholic is turned down for a sheltered housing placement because of long-ago crimes related to his addiction.

On a daily basis, Julie McCormack, senior clinical instructor and director of the Safety Net Project at the WilmerHale Legal Services of Harvard Law School, witnesses the devastating effects even a minor criminal record can have on her clients’ ability to secure housing, government benefits or employment.

After Massachusetts passed a criminal justice reform bill in 2018 expanding the opportunities for citizens to seal criminal records and creating a streamlined administrative and court process, the LSC launched free Criminal Offender Record Information (CORI) sealing workshops, providing walk-in appointments for clients seeking help.

“On the individual level, we are privileged to see how this directly changes people’s lives — how much easier it is to get a job, to get housing, to do any number of things that we all take for granted but that are denied to folks with a criminal record, who otherwise have their sentence extended indefinitely — long after they have been released,” McCormack said.

On the third Tuesday of every month, Harvard Law students guide eligible clients (some with misdemeanors from three or more years ago, and most with felonies from more than seven years ago) through the process of getting convictions and other dispositions on their CORIs administratively sealed with a petition to the Massachusetts Probation Department. For those who need to present their case in front of a judge (individuals with more recent nonconvictions), students help prepare the client to testify and to assemble a package of mitigating evidence including an affidavit detailing the challenges the client faced in securing employment or new housing because of their criminal record, in an effort to convince the judge to promptly seal their CORI rather than make them endure the full waiting period to administratively seal.

Even though the CORI workshops at LSC have been in place for just a few months, everyone involved is satisfied with the results so far: Community partners can refer their people for direct assistance; staff, law students, and volunteers derive immense satisfaction from the role they play in helping change lives and in mitigating some of the harms of mass incarceration; and clients get the assistance they need to truly start fresh.

5:30 p.m.: Making the case for veterans’ benefits

WilmerHale Legal Services Center of Harvard Law School, Jamaica Plain

For nearly a month, Nicholas Cordova ’21 and Maura Cremin ’21, students in Harvard Law School’s Veterans Law and Disability Benefits Clinic, reviewed health and service records, and conducted legal research, to make a case for why the Board of Veterans’ Appeals was wrong to deny disability benefits to their client, an Air Force veteran.

They spent several weeks identifying legal errors in the board’s decision to deny their client’s disability claim, and then submitted a “Rule 33 memo” summarizing the issues that they intended to argue before the U.S. Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims. All of their work came down to a “pre-briefing” conference call this afternoon, when an attorney from the Department of Veterans Affairs would decide whether they agreed with the students that the board made errors in its decision or the case would proceed to full briefing before the court.

After submitting their memo, the students prepared to negotiate with the VA attorney on the call, trying to practice a response for every possible outcome. Cremin says her strategy was to “prepare for the worst, hope for the best, and be prepared to get a lot of pushback.”

In the end, the VA attorney was convinced by the Harvard Law students’ arguments and agreed to remand the case back to the Board of Veterans’ Appeals, including instructions for a new medical examination. Their successful negotiation allowed their client to avoid potentially lengthy litigation and gave him another opportunity to submit additional evidence to bolster some of his claims before the board.

“By avoiding court, we saved the veteran months, and potentially years, before his claim is ultimately adjudicated,” said Cordova.

For Cremin, the experience of defending vulnerable veterans has broadened her perspective on legal work and the ways in which law affects people’s lives. It has also taught her that there are just some things that you can’t learn in a classroom.

“The skills of writing a brief, the skills of writing a memo, of doing legal research,” she said. “We get those in the classroom, but how to interact with clients, how to convey legal knowledge to somebody in a way that’s both useful and respectful of them — those are skills you only learn hands-on.”

6:30 p.m.: Protecting housing rights

284 Amory St., Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts

A booming economy with skyrocketing real estate prices has created a housing crisis in Boston, leaving many low-income tenants fighting an uphill battle to retain their homes. Using a sword and shield approach, Harvard Legal Aid Bureau students help tenants fighting eviction by working in partnership with City Life/Vida Urbana, a grassroots organization which fights forced displacement.

As they say here at City Life, when we fight, we win.

Dennis Ojogho ’21

HLAB students provide legal services and advice, “a shield,” while City Life/Vida Urbana provides “a sword,” by organizing tenant associations and eviction blockades.

In the course of dealing with complex problems like the displacement of people from their homes and the lack of affordable housing, Dennis Ojogho ’21 says he’s learned effective advocacy happens when people, especially lawyers and nonlawyers, work together. For a year, he and Jeremy Ravinsky ’20 worked with their client Michelle Ewing, successfully preventing her eviction from the apartment she has lived in for more than 25 years.

Tonight, Ojogho, Ravinsky, and Ewing celebrate that success with the City Life community, sharing how they stayed calm at the negotiation table as the opposing side shouted and reacted in anger—and they won.

“What drew me to this work is a very fundamental belief that housing and a home is a human right,” said Ojogho. “I have a lot of privilege to be a Harvard Law student with the training and access to resources through the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau to help make a difference in the community that I live in today.”

Ojogho says his clients are incredible advocates and have taught him no matter how dire the situation may appear, you don’t give up. “As they say here at City Life, when we fight, we win.”

7:00 p.m.: Learning how to be successful advocates

Wasserstein Hall, Harvard Law School, Cambridge

What lawyers should know when working with clients who have experienced trauma is the focus of the presentation Virginia Wright ’21 is delivering tonight to a class on employment law advocacy at HLS. As a student in the Employment Law Clinic this semester, Wright is working at the law firm of Sherin and Lodgen, in Boston.

The clinic, under the direction of Lecturer Steve Churchill ’93, focuses on rights in the workplace, with a particular emphasis on state and federal laws that prohibit discrimination, harassment, and retaliation based on race, sex, disability, and other protected characteristics. Students work with clients to address issues such as unemployment benefits, wage and hour claims, severance negotiations, union issues and workplace safety.

“The burden of building a relationship with clients is on us as attorneys,” said Wright. “We must learn how to recognize and respond to trauma signals if we want to be successful advocates.”

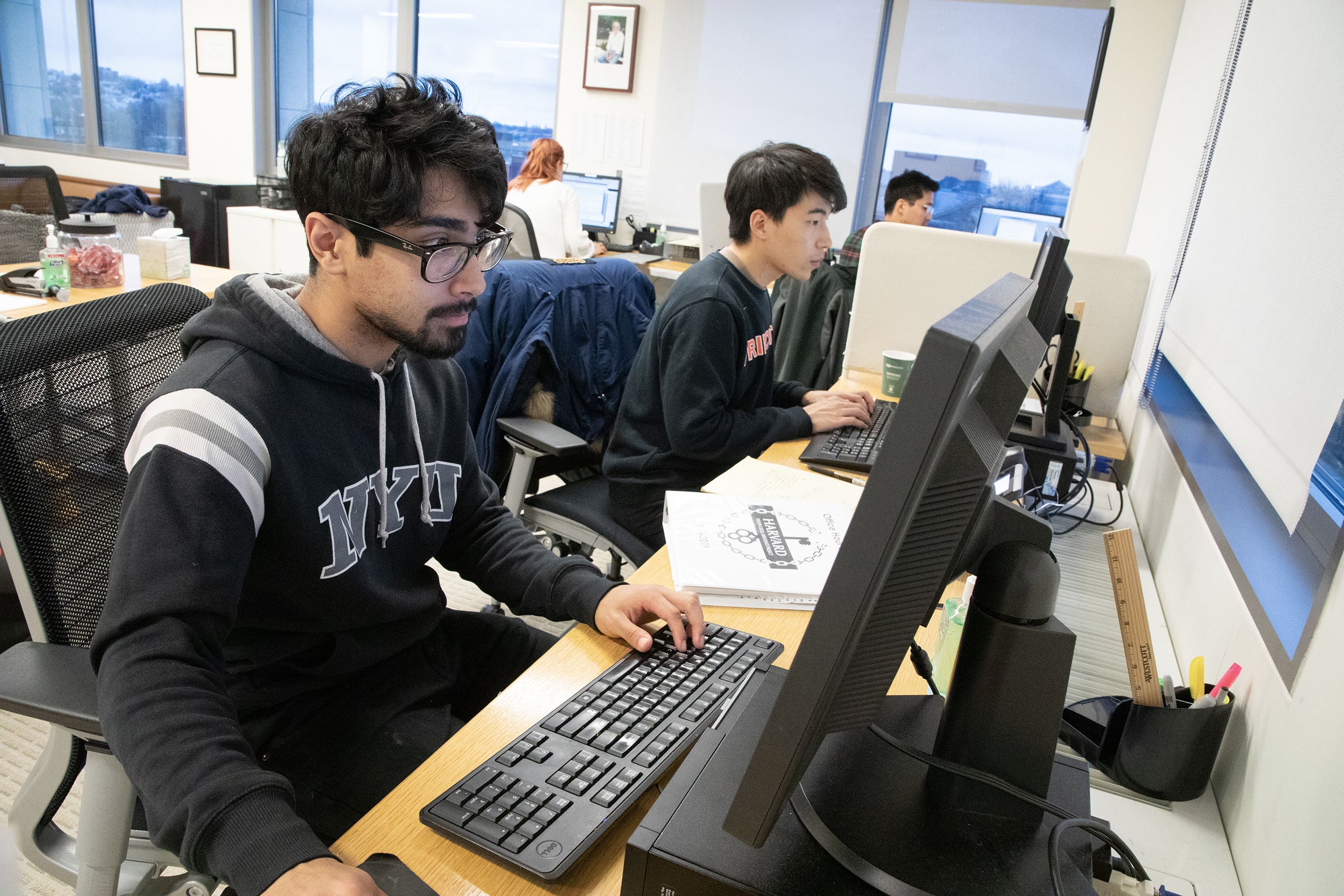

10:00 p.m.: Late-night immigration court filing

Wasserstein Hall, Harvard Law School, Cambridge

At this hour, the halls of Harvard Law School’s clinical wing are quiet and offices lining the hallway are mostly dark. But on the third floor, in the suite that houses the Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program, the lights are on.

Two students, Eun Sung Yang ’20 and Michael (Ki Hoon) Hur ’20 — who just yesterday filed a 65-page brief in another case (a Third Circuit appeal for a woman from Mexico who had fled domestic violence) — have settled in for the night to work on an immigration court filing that is due in just a few days for their client, a refugee from Sudan who is seeking protection under the Convention Against Torture. There is no right to counsel in immigration cases, even for children. Clients in immigration proceedings have to hire counsel at their own expense, represent themselves or find pro bono counsel. HIRC helps fill that critical gap by representing more than 100 clients annually.

Both Yang and Hur say they chose HIRC because it offers the opportunity for direct representation, but engaging with clients and hearing intimate details of the trauma they have endured — from torture to kidnapping to sexual assault — is a difficult aspect of the work that affects them on a personal level.

“To see my client talk about it, share intimate details, and even be retraumatized talking about it, that’s really challenging,” said Hur. Yang agreed and added that it helps a lot that there is a social worker on staff in the clinic to support both the clients and the students.

As international students, both originally from South Korea, Yang and Hur say addressing issues of immigration is also personal. “My experience as an immigrant in America is very different from my client’s experience as an immigrant in America, but what’s separating us is random, a stroke of luck,” said Hur. “I happened to be born and have lived in countries where I was always safe and I was able to pursue my education and fulfill my potential.” He says he hopes to use that privilege to help his clients have the opportunity to live happy prosperous lives in the United States.

11:00 p.m.: ‘We end up working more because we care about the work that we’re doing.’

1607 Massachusetts Ave., Harvard Law School, Cambridge

As the last few Harvard Law students turn out the lights and head home for the night, many others are preparing to take their turn in the days and weeks ahead to learn practical legal skills while working to improve people’s lives. Over the course of 18 hours, scores of students involved in just 15 of the School’s many legal clinics have made a difference in the lives of hundreds of vulnerable people around the globe.

Perhaps the only typical thing about any day in the life of Harvard School’s legal clinics is that they transform lives every day of every week.

HLS Clinics in Action was a collaborative project between the HLS Office of Communications and the Office of Clinical and Pro Bono Programs. A special thank you to the numerous staff, faculty and students who assisted.