“Thirsty men want beer, not explanations,” said U.S. Supreme Court Justice David Souter ’66, quoting Lord Macnaghten, after presiding over the 89th annual Ames Moot Court Competition. And “beer” is what the Ames competitors delivered.

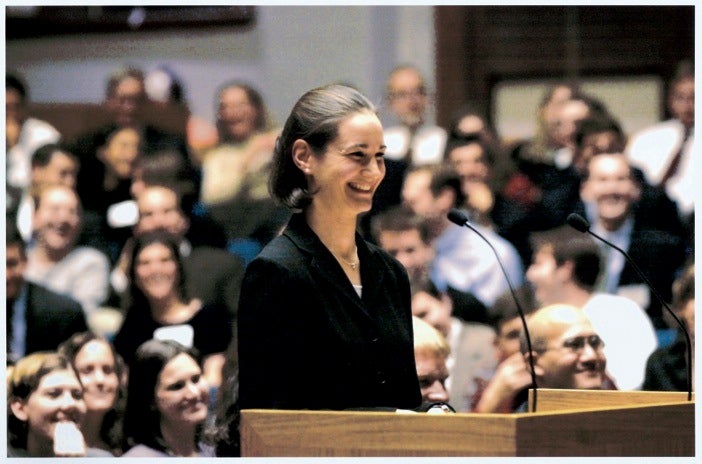

Souter, with Frank Easterbrook of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit and Judith Rogers ’64 of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, heard the case Mary Cameron & David Rae v. State of Ames in a packed Ames courtroom on November 16, 2000. The Myra Bradwell Memorial Team, representing respondent, the State of Ames, won the honors of best team and best brief, with team member Jessica Ellsworth ’01 being named best oralist. The David A. Charny Memorial Team represented petitioners, Mary Cameron and David Rae.

The case involved a challenge to an Ames statute that restricted protest activity near a health care facility. Petitioners, registered nurses in the State of Ames, were employed at the Ames City Health Clinic (ACHC), a nonprofit community clinic that provides general health care services including abortions. They were also members of the Ames Nurses’ Association (ANA), which was dissatisfied with several workplace issues, specifically regarding wages. To raise public awareness of these complaints, the ANA decided to demonstrate outside the Kennedy Building, a municipal building that included the offices of the Ames Board of Nursing and the ACHC. Members of the ANA, after engaging in peaceful protests, were asked to leave the area, first by the building security guard and subsequently by the Ames police. Petitioners refused, and were arrested.

The Ames Superior Court found petitioners guilty. The Ames Supreme Court affirmed. The U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari to determine if the Ames legislation unconstitutionally curtailed expression in a public forum, and if the legislation was unconstitutionally overbroad and vague.

The Ames statute was similar to the legislation challenged in the recent U.S. Supreme Court case Hill v. Colorado, 120 S. Ct. 2480 (2000). However, unlike Hill, this case involved the enforcement of health care clinic legislation concerning a protest on wages, not abortions. Justice Antonin Scalia ’60, dissenting in Hill, 120 S. Ct. 2503, foreshadowed a similar scenario: “I have no doubt that this regulation would be deemed content-based in an instant if the case before us involved antiwar protesters, or union members seeking to ‘educate’ the public about the reasons for their strike. . . . But the jurisprudence of this Court has a way of changing when abortion is involved.”

Richard Squire ’01 presented first for petitioners, arguing that the legislation was “unconstitutional on its face” on the basis that it was “not narrowly tailored to further [the] state interest” of “promoting access to medical care.” Squire argued that the legislation’s “12-foot no-approach zone” effectively “precludes dialogue, and not just in-your-face speech,” and further, that “having the ability to engage in dialogue is central to the First Amendment.” Squire also said that the legislation’s other provisions, including the requirement that protesters receive the “clear consent” of potential listeners before approaching; its restrictions on picketing, leafleting, providing information to listeners, and others; and its reach to 120 feet within all health care facilities, lead to the “substantiality of its burden upon speech.”

In addition, said Derek Ho ’01, also for petitioners, “Even if this court finds that the Ames statute is constitutional on its face, it should strike it down as applied to petitioners.” The state interest in protecting patients, according to Ho, did not justify convicting petitioners for “engaging in a peaceful demonstration that was aimed not at patients, but at the government, their employer, and the public at large.”

Souter asked Ho whether there was “any practical way that the patients can be protected if the ambit of the statute does not apply to approaches to nonpatients as well,” and further, whether the “multiuse” public nature of the Kennedy Building posed any particular problem for the petitioners’ case. Ho responded that the petitioners’ free speech right allowed them to protest “against the government at the site of . . . government decision making.” Ultimately, according to Ho, the law that was designed to protect patients was used to protect “many more people than merely patients,” making the statute unconstitutional as applied to petitioners.

Robin Wall ’01, for respondent, argued that “this is a case about the ability of the state to protect its citizens’ right to obtain access to safe and effective health care.” Wall argued that petitioners did not demonstrate either that “they did not cause the harm” that the legislation targeted, or that the legislation “substantially limits or impairs their ability to protest and demonstrate.” Supreme Court precedent that limits certain methods of communication does not, in itself, amount to “an abridgment of the First Amendment right to speech,” he said. Ultimately, Wall said, the legislation provided an adequate balance between patients’ rights of access to “meaningful and safe [health] care” and petitioners’ “meaningful right” to protest.

Winning oralist Jessica Ellsworth, also for respondent, emphasized the state’s interest in providing a “cushion” to Ames citizens entering or passing by health care facilities. The state was not concerned with the content of protesters’ speech, but rather with their approach, she said. In support of this interest, Ellsworth relied on medical literature identifying potential problems caused by protesters approaching patients on their way to receive medical treatment. To the crowd’s amusement, Ellsworth described the difference between approaching a health care facility “between two parked cars” and “two cars that are rolling toward you.” According to Ellsworth, the legislation “protects the rights of [willing] listeners, who are interested in receiving this information, to approach and get it, and protects the rights of unwilling listeners, who are captive to medical necessity, to gain entrance to the health care facility.”

After announcing the awards, the judges praised the efforts of both teams, including advocates and brief writers, who, according to Souter, were “credits to Harvard Law School.” Easterbrook noted that advocates need to understand that judges, through an exercise of dialogue with counsel, are “interested not so much in what happens today, but what happens tomorrow; what principles are on the line; how do you explore those principles?” According to Easterbrook, both teams “engaged in that enterprise.”

Ames Fellow Trevor Farrow LL.M. ’00 wrote the case and prepared this report.

The Teams:

The David A. Charny Memorial Team, representing Petitioners: Timothy Casey, Jennifer Daskal, Derek Ho, Richard Squire, Andrew Wilmar, and Robert Wolinsky

The Myra Bradwell Memorial Team, representing Respondent: Craig Cronheim, Jessica Ellsworth, Danielle Leonard, Michael O’Shea, Stacie Somers, and Robin Wall

The Winners:

The Myra Bradwell Memorial Team, best team and best brief; Jessica Ellsworth, best oralist