People

Scott Westfahl

-

How GCs Can Lead While Careening Through Crises

October 17, 2022

In-house counsel seem to be facing one crisis after another these days, from COVID-19 and the wear in Ukraine to climate change. “General counsel are…

-

Practicing Law in the Wake of a Pandemic

July 15, 2022

‘Everyone is struggling to understand what this new world is going to look like’

-

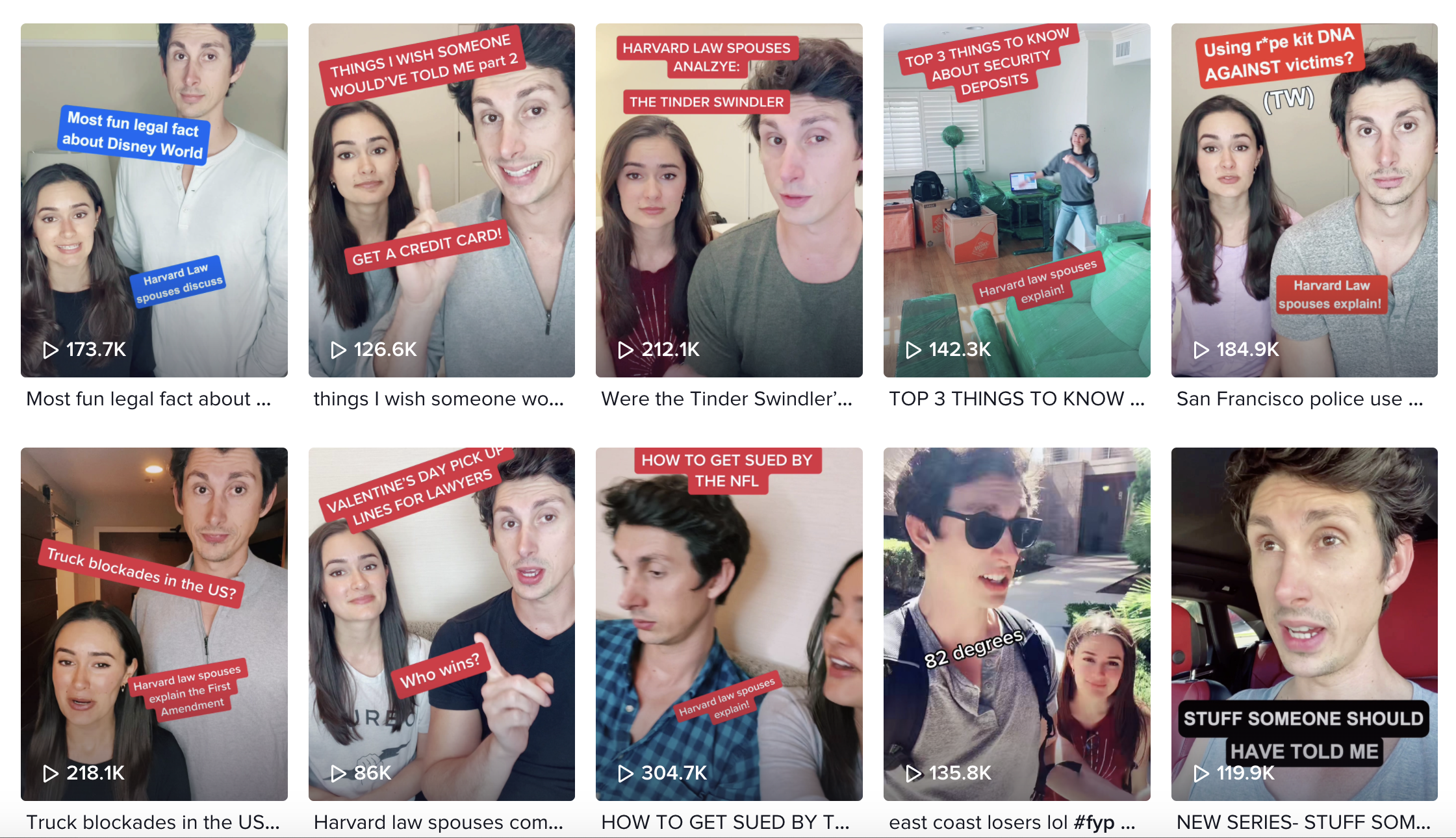

Ashleigh Ruggles Stanley ’18 and Maclen Stanley ’18 use social media as a teaching opportunity to help people understand legal terms and current events.

-

Law Firms Love To Talk About Culture. But Can They Define It?

January 18, 2022

Throughout the pandemic, law firms have uttered the word “culture” in a variety of contexts and implications—how their culture distinguishes the firm in the war for talent, how their culture has evolved to accommodate remote and hybrid work, why getting back to the office is so crucial to maintain culture. ... “Industrial psychologists would say, there’s a concern that you’re always trying to manage the delta—the difference between what the company says it is and what people experience on the ground,” said Harvard Law professor Scott Westfahl.

-

Will Associates Benefit From Early Career Milestones?

November 23, 2021

Sidley Austin, taking a page from other professional service industries, recently announced that it is doling out new titles to associates based on seniority as a way to better reflect “where” associates are in their career. With indicators showing the the track to partnership only lengthening, is there value in providing more waypoints toward the coveted counsel or partnership promotion? “There is a long gap between associate and partner, so in some ways it makes sense to create and acknowledge with titles different levels of role. That can help with retention, assuming that the titles are meaningful,” Harvard Law professor Scott Westfahl said.

-

‘Don’t just be a lawyer. Be a strategist’

November 10, 2021

The Center on the Legal Profession convenes experts from public and private sectors for a day-long symposium on crisis lawyering.

-

The pandemic has changed Sarah Shahatto’s perspective on her career. It has made the third-year law student at the University of California Irvine School of Law question, and reimagine, her future as an attorney...Harvard Law School professor Scott Westfahl says it will take a lot more than pro bono programs to give attorneys a true sense that their work has purpose and meaning. Even before Gen Z attorneys enter the workforce in meaningful numbers, the pandemic has primed their concern, as isolation and burnout take their toll on the legal industry and the world at large. Westfahl has gotten multiple calls in the past few months from former students who are now junior associates, and even partners, who feel as if the pandemic has sapped away any meaning from their work. “I’m getting calls every week from students that graduated years ago that say, ‘I’m burned out’ and are starting to question whether it all matters,” Westfahl says. “For a long time many people found meaning and purpose coming into a beautiful office with their name on the door and being in an office together with really smart and interesting people,” he continues. But that won’t move the needle anymore.

-

Throughout 2020, Big Law firms were said to be “cleaning house”: pushing out unproductive partners so they could pay top earners more and tidy up their expense sheet as the pandemic raged and business development costs promised to return in 2021. Yet the nonequity tier, long viewed as a common target in these efforts in part because of the fixed costs and salaries of an income partner, grew roughly 6% last year among the Am Law 100...Harvard Law professor Scott Westfahl, who runs an executive training program for Milbank and other Big Law firms, says the law firm up-or-out model, while historically effective, leaves out many people with substantial expertise. It creates no space for good attorneys who simply want to practice law and not devote a significant portion of their time to generating business. Firms that don’t want to lose this expertise, he says, should look to McKinsey + Co.’s “grow or go” model, wherein an employee doesn’t have to strive for McKinsey’s version of equity partnership if they instead consistently look to expand on their expertise and diffuse it throughout the firm. Law firms can still retain the up-or-out model while including “branches” for attorneys who don’t want to make equity partner, Westfahl suggests.

-

Sharing stress strategies

October 14, 2020

For ABA Mental Health Day, five faculty share struggles from their own law school days and offer options for coping and support.

-

Law Firm Culture Will Determine Whether Younger Attorneys Sink, Swim or Simply Float Away

September 28, 2020

Firms love to talk about “culture” when it comes to distinguishing themselves, but while it can be key to attracting lateral partners, it can also be a critical factor in limiting associate development. That’s particularly true when firms are adopting special measures as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, many of which have hit associates hard. If firms don’t pay attention to key characteristics like transparency and feedback, they run the risk of losing younger talent, industry observers said. Experts agree that competition for talent is growing more fierce as more junior attorneys realize they have options outside of their current firms or even away from Big Law, and culture plays a larger role than ever in firms attracting and retaining the talent that can push them ahead of their competitors. Culture is often a reflection of leadership. Scott Westfahl, professor of practice and director of executive education at Harvard Law School, has an interesting definition of what leadership means. “Leadership is about disappointing people,” he said. “That is the lens on it, and it is such a critical thing to understand. You are going to need to make changes as the world changes. The better your articulate who you are, why you are, the better you will be able to make principled decisions.” Westfahl said he has worked with firms in the past that have clear, defined culture and values, many times embedded in the firm’s strategic plan, literally written down for all to see. But he has worked with many more that have a looser, more ambiguous approach to defining their firm culture, and that can create a problem. “A lot of law firms haven’t been specific about defining their culture and their values,” Westfahl said. “The Big Four have been much more deliberate. When you have an inspiring mission, people can rally around it. When you have to make hard decisions, you at least have the framework around how to make those decisions, and you can explain to those who aren’t happy why the decisions were made.” Westfahl said that absent that, you can create a situation where there can be the perception of favoritism or unfairness when it comes to difficult decisions like salary cuts or layoffs, work allotment or promotion.

-

How Can Law Firms Thank Associates Without ‘Throwing Money at Them’?

September 25, 2020

Many associates at top firms are ecstatic to see that they will receive thousands of dollars in the form of special fall bonuses. But given the precariousness of the COVID economy, and the damage it has wreaked, are there other ways firms can show appreciation for their associates when bonuses are out of the question? Big Law has constantly turned to money as the go-to lever for recognizing good performance. This trend is perhaps best evidenced by the annual year-end bonus wars, where Big Law firms attempt to one-up each other in who can dole out bigger bonuses to their associates—even when experts denounce the practice as short-sighted and fiscally irresponsible. So it should come as no surprise that this year, many Big Law firms announced special fall bonuses to associates as gestures of appreciation for their work during the pandemic...But given the uneven effect the pandemic has on firm finances, bonuses may not be possible at some firms without finding extra money through layoffs of staff and associates, leaving firms in a tricky situation. Can firms show appreciation through other means? “At the associate level, associates should understand that in the long run across their careers… minor variations in bonuses are a small rounding error and reading too much into them or getting upset about perceived inequity is not helpful,” said Scott Westfahl, director of Harvard Law School’s executive education program. Westfahl acknowledges that associates host an “automatic, primal” sense of frustration when they hear of bonuses at peer firms. Still, there are many ways to show appreciation for associates: enhanced professional development, coaching, mentoring and training; interesting work and “stretch” assignments; more flexibility; internal leadership opportunities; and recognition internally and externally, to name a few.

-

Can Law Firms Fix the Leadership Gap Before It’s Too Late?

September 2, 2020

When Scott Westfahl was a boy, he watched as his father climbed the ranks of the U.S. Navy. Every few years he’d get a new stripe, denoting a new level of leadership and responsibility. Each time, he was put through rigorous training to prepare him for his new role and give him the skills to succeed. By the time Westfahl’s father was ready to captain his own submarine, the Navy put him through prospective commanding officer school, an intense six-month stretch that taught him about tactics and operations, understanding and guiding strategy and, perhaps most important, how to lead. Years later, after the younger Westfahl graduated law school and took a job at Foley + Lardner, he moved through a series of leadership roles himself. But the only training he received was substantive. What he learned about leadership, he learned by doing. “There was no organized thought about it at all,” he says. “And that really hasn’t changed much.” It wasn’t until Westfahl left the law to work in professional development at McKinsey + Co. that he realized the legal industry set itself apart from not just the military and consultancies but most of the professional world by failing to devote significant resources to leadership training and development. Now, as the director of executive education at Harvard Law School, he’s working, one cohort of lawyers at a time, to change that. “In the law firm world, the word leadership just isn’t used except at the top levels,” Westfahl says. Instead, industry consultants and observers say, many firms pay scant attention to developing leaders throughout their organizations, keeping a tight focus on the daily pressures of operating what for many is a billion-dollar business. In many cases, a lawyer might receive only fleeting opportunities to think or learn about leadership until the moment they assume a role that demands exactly the experience that has thus far eluded them.

-

The early weeks of the coronavirus crisis were fraught with immediate challenges for law firms. But in the months since, as the industry and the world have adjusted, many of the initial work issues associated with the pandemic have been addressed. Yes, people can work from home. Yes, deals can be done remotely. Yes, Zoom and other platforms can be effective for interpersonal communications. Law firms are entering another phase of the pandemic fallout: Now that the immediate needs have been met, how can they plan for the future? Complex questions around safety and equity are now paramount. And one of those questions is how firms are going to train, coach and develop their talent in an effective and equitable manner at a time when the circumstances of their dispersed workforces are both inconvenient and inconsistent. “At most firms, there are no systems, structures and professional staff in place that are focused on these kinds of issues,” Scott Westfahl, professor of practice and director of executive education at Harvard Law School, says...Westfahl, a Big Law veteran of both Foley + Lardner and Goodwin Procter, says work allocation systems are critical to bringing everyone along at an appropriate pace. “My model for this is the consulting firms,” he says. “Partners there couldn’t give work to associates without the professional development person saying it fairly meets the needs of the associate body.” After the Great Recession, law firms emerged with what Beese describes as “holes” in their partner classes due to lack of leadership around career progression and talent development. “Firms had two or three years where they only had two or three people left in their classes,” he says.

-

Partners’ Gain Is Associates’ Pain as Hours Move Upstream

August 13, 2020

Law firm partners are taking a larger share of available work during the pandemic, driven by client demand and anxiety about billable hours, and associates are paying the price. A recent peer monitor index by Reuters highlighted the downturn in overall work for law firms in Q2 of 2020 (-5.9%), while the average billed rate increased (+5.2%), showing how higher-rate partners are taking work formerly done by associates and paralegals. Experts agree that, while this has happened before, the industrywide trend has consequences both short- and long-term...Some of that shift is, in fact, due to partners wanting to hold onto work, and in a zero sum game of billable hours that has consequences for those missing out on said work. “In the short term, it is anxiety-producing for associates as their hours are reduced,” Scott Westfahl, director of Harvard Law School’s executive education program, said. “And most associates are smart enough to notice.” Westfahl said that, longer term, there is what he called “associate lag,” where they are not given sufficiently challenging work in order to develop and grow professionally, which means that, although their total years in the profession indicate one thing, their actual experience level is that of someone more junior. “One of two things will happen: Either they get stuck as their rates rise each year and they don’t have the experience to handle it and their performance rating goes down, or they get bored out of their minds,” he said. The end result is lack of knowledge for certain classes of associates and an increase in the associate’s desire to seek employment elsewhere once economic conditions are ripe for a move to another firm.

-

Is a 2-Week Summer Associate Program Even Worth It? Kirkland Isn’t the Only Firm That Thinks So

May 8, 2020

Kirkland + Ellis, Sidley Austin, Baker + Hostetler and other law firms announced this week that they are dramatically shortening their traditional summer associate programs—which are already being held virtually given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Kirkland’s program will last two weeks with a June 15 start date, while Sidley’s summer associate programs will be at least four weeks long, the firm said Thursday. Sidley’s program in New York will start July 6 and end July 31. Both firms are paying their associates what they were set to receive when the programs were running at full length. Kirkland is extending job offers to associates who graduate from law school in 2021, while associates who graduate in 2022 will be able to participate in next year’s program...With in-person programs already a thing of the past for most firms in 2020, is it even worth the trouble to invite summer associates for such short periods? Scott Westfahl, a professor of practice and the director of Harvard Law School’s executive education program, said the answer is yes. A two-week virtual program is better than no program at all, he said. Westfahl said a short visit can be useful, noting that law firms in the past have brought past summer associates back for two-week programs designed to reconnect with partners. “If they are thoughtful about it, [the program] can provide a meaningful experience to build their networks among each other and among the lawyers at the firm,” Westfahl said of the firms’ efforts.

-

Health care general counsels explore pressing health policy and legal issues at Harvard Law School

December 11, 2019

The General Counsels Roundtable helps influential health law attorneys stay on top of or even ahead of changes in health law and policy. The roundtable connects GC to experts at HLS and the broader university, while also strengthening ties between faculty and legal practice.

-

JET-Powered Learning

August 21, 2019

1L January Experiential Term courses focus on skills-building, collaboration and self-reflection

-

The Way Forward For Law Firms Is Less Hierarchy

April 10, 2019

Regulations preventing nonlawyers from holding equity in a law firm are just one piece of an outdated culture holding law firms back, and the market won’t wait for them to come around, two law professors warned a conference of legal industry marketers on Tuesday. Nonlawyers—or “allied professionals” in the speakers’ preferred language—within law firms are increasingly vital to the successful operations of the firm, according to Bill Henderson, a professor at Indiana University Maurer School of Law, and Scott Westfahl, professor of practice and faculty director at Harvard Law. ABA Model Rule 5.4, which prohibits non-lawyer ownership in a firm, has held these professionals back from full participation and investment in the organization—often to the firms’ detriment, the professors said. According to Westfahl, there was little basis for the logic behind the regulation — namely, that non-lawyer owners would put the commercial interests of the firm over those of the clients.