People

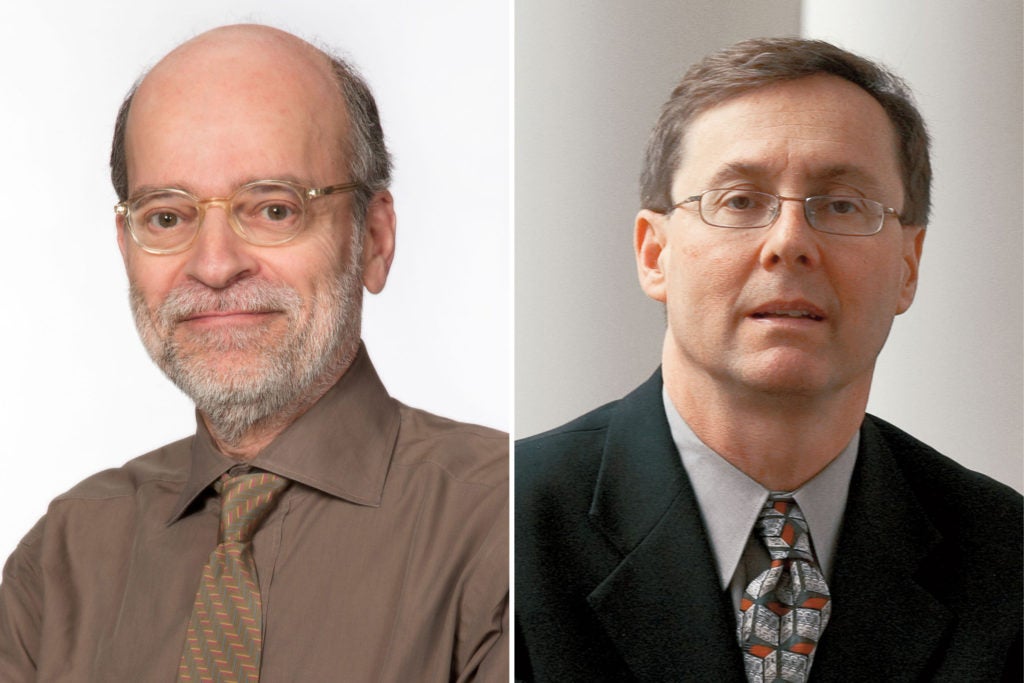

Roberto Tallarita

-

Roberto Tallarita S.J.D. ’23, a lecturer on law and the associate director of the Program on Corporate Governance at Harvard Law School, has been named an assistant professor of law at Harvard.

-

New faculty appointments

April 18, 2023

Harvard Law School expands the ranks of its faculty with four appointments.

-

Articles by Harvard Law faculty and alumni among top ten corporate and securities articles of 2021

June 22, 2022

Articles by four Harvard Law faculty were selected in an annual poll of corporate and securities law professors as three of the ten best corporate and securities articles of 2021.

-

The E in ESG Means Cancelling the S and the G

October 19, 2021

Price rises—they keep on coming. Even before the recent surge in energy prices, companies had been warning about inflationary pressures in their supply chains. ... Government climate policies, such as biofuel mandates, help drive up the cost of energy and food. So do non-commercial decisions made by business and Wall Street. In his 1970 essay on the social responsibility of business, Milton Friedman wrote that when a corporate executive makes expenditures on pollution reduction beyond what’s in the best interests of the corporation or required by law, that executive is, in effect, imposing taxes and deciding how the tax proceeds should be spent. In their critique of the doctrine of stakeholderism as propounded by the Business Roundtable in its August 2019 statement of corporate purpose, Harvard Law School’s Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita note the Roundtable’s denial of the reality that the interests of shareholders and stakeholders can clash. Freeing directors from shareholder accountability puts directors in the position of adjudicating these trade-offs and elevates them to the role of social planner—“the ideal benevolent entity conjured up by economists to model socially optimal outcomes.”

-

President Biden embraced a pro-labor stance during his campaign. He has underlined his ambition to support workers’ interests by nominating as his future labor secretary Boston Mayor Marty Walsh, who was strongly backed by the AFL-CIO and major labor unions. While there should be no disagreements with the goal of improving the situation of the labor force in the United States, there could be some merit in taking a closer look at possible side effects...A Harvard Law School paper published by professors Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita warned of the consequences and showed that such stakeholderism would impose substantial costs both on stakeholders and society. It would also hurt the owners—namely the investors. This is exactly the result we see in Germany. Only 16% of Germans own equity-based investments, and only 7% directly own stocks; in the U.S., in contrast, 55% of people own stocks (either directly or through instruments like mutual funds).

-

Norfolk Southern Corp. shareholders yesterday approved a resolution calling on the coal-reliant railroad company to report on how its lobbying aligns with the Paris Agreement. The resolution was the fifth political influence-related proposal at a Fortune 250 firm to gain a majority of shareholder support this annual meeting season, according to data compiled by the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank. The string of shareholder victories comes as banking giant JPMorgan Chase and Co., oil major Exxon Mobil Corp. and tech titan Amazon.com Inc. are set to face similar resolutions later this month. Experts think momentum is building in favor of greater disclosure of corporate spending on lobbying and politics...Shareholders rarely approve public-interest proposals, according to a new research paper from Roberto Tallarita, the associate director of Harvard Law School's program on corporate governance. He defines those as ones focused on political, social and environmental issues. In Tallarita's review of more than 2,400 resolutions presented to S+P 500 companies over the past decade, "only a minuscule fraction of public-interest proposals obtain a majority of votes (about 1% in my 10-year sample)," he wrote in an email. In that context, a handful of successful political influence resolutions already this year is remarkable.

-

The Rise of an Antitrust Pioneer

March 10, 2021

Word that the White House plans to pick Lina Khan, a Columbia Law professor whose research has spurred a rethinking of competition law, for a seat on the Federal Trade Commission has Washington and business types speculating that the Biden administration is preparing to get tough on antitrust...Concerns about political donations already top investors’ E.S.G. proposals, according to new research from Roberto Tallarita, an associate director of Harvard Law’s corporate governance program. Among the findings from his survey of shareholder public interest proposals from 2010 to 2019: Political spending initiatives made up 16 percent of all shareholder efforts, and on average drew support from 28 percent of companies’ investors, the highest level for such proposals. Companies sought S.E.C. permission to exclude only 19 percent of political spending proposals, compared with 37 percent of climate change initiatives and 57 percent of animal welfare ones. That suggests that demands for transparency on political spending are becoming mainstream and are generally accepted by management teams and the S.E.C. as a legitimate issue. “If the S.E.C. mandates disclosure of political spending, as it might, it will be in large part, as Gensler made clear in his confirmation hearing, thanks to the constant pressure from investors,” Mr. Tallarita said.

-

The Business Roundtable’s Statement on Corporate Purpose One Year Later

December 15, 2020

It’s been a little over a year since the Business Roundtable (BRT) issued its much-ballyhooed statement on corporate purpose. Many of the commentators who welcomed it rapturously predicted the statement would usher in a new era of corporate social responsibility (CSR), with corporations tackling a range of social problems such as climate change and racism. After a year in which society and business have faced unprecedented problems, it seems fair to ask whether corporations have really embraced the BRT’s vision of corporate purpose...Further evidence that the BRT statement was mostly greenwashing comes from surveys by legal scholars Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita. They found that most CEOs who signed the statement had not gotten approval to do so from their companies’ board of directors, which one would expect in the event of a major shift in corporate policy and purpose. They also found that the corporate governance guidelines of a sample of signatory firms had not been modified to reflect the statement’s emphasis on social responsibility and stakeholders. To the contrary, as they pointed out, “explicit endorsements of shareholder primacy can be found in the corporate governance guidelines of the two companies whose CEOs played a key leadership role in the BRT’s adoption of its statement.” ... In an open letter to the CEOs of the signatory firms, management academic Bob Eccles pointed out that the logical next step would have been for their boards to “publish a statement explaining the specific purpose of your company,” but “not a single one of your boards has published such a statement.” Bebchukand Tallarita’s argument that boards are not even talking the talk, let alone walking the walk, remains valid.

-

Governance experts call for US Stakeholder Capitalism Act

November 3, 2020

The US debate over the future of capitalism continues to flare with a proposal for new legislation that would shift companies away from “shareholder primacy” and into the realm of “stakeholder governance”. A newly published white paper, from non-profit organisations B Lab and The Shareholder Commons, proposes the US push through a Stakeholder Capitalism Act containing measures to give both company directors and investors revised fiduciary duties. In an article for the Harvard Law School governance blog, the paper’s authors argue that there is a need for urgent reform while insisting the best elements of capitalism must be retained. They say their policy measures are “designed to maintain the market mechanism inherent in profit-seeking but correct market failures that allow for profits derived by extracting value from common resources and communities, including workers.” Their legal reforms, they say, consist of “revised fiduciary considerations that extend beyond responsibility for financial return…” Among the key changes, the writers call for reforms that give investors a requirement to consider the “economic, social and environmental” implications of their decisions. The white paper also calls on investors to report on how they have met these new responsibilities...In the US, the debate around stakeholderism, or “purposeful” business, has been ongoing for some time. But in August last year the discussion was jet-fuelled when the Business Roundtable—a club for corporate leaders at some of the largest US corporates—declared its members would become “purpose-driven” corporates. A year on and a blizzard of articles have poured cold water on the idea that anything is different. Perhaps the most notable comes from academics Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita, who say they found little evidence of change in Roundtable members. “Notwithstanding statements to the contrary, corporate leaders are generally still focused on shareholder value. They can be expected to protect other stakeholders only to the extent that doing so would not hurt share value,” they write in the Wall Street Journal.

-

Stakeholder Capitalism Needs Gov’t Oversight To Work

November 3, 2020

Despite the urgent pressure of COVID-19 and other crises brought to us by 2020, stakeholder capitalism — the idea that corporations should take into account the interests of their stakeholders, not just shareholders — has remained at the top of the corporate news cycle. On the recent 50th anniversary of economist Milton Friedman's essay "The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits" — which established shareholder primacy as the prime corporate directive — many legal, business and economic leaders challenged Friedman's legacy, favoring stakeholder capitalism over shareholder primacy. We think that it isn't an either/or situation. Stakeholder capitalism can work to benefit shareholders as well, but there must be collaboration between business and government in order to achieve the desired goals. In fact, a review of recent history shows us that collaboration between business and government is the optimal way to determine what is in the best interests of the stakeholders...How can we restore confidence? Stakeholder capitalism can help, by increasing the accountability of institutions for the constituencies they affect. However, in order for stakeholder capitalism to work, the government needs to take a central role, because corporations are not legally accountable to any parties other than their shareholders and the government. Moreover, corporate leaders are not incented to prioritize the interests of stakeholders, as concluded in a recent study by Harvard professors Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita. And under corporate law in Delaware, where most large corporations are incorporated, directors have fiduciary duties to make decisions in the best interests of shareholders — not stakeholders. Delaware public benefit corporations allow directors to weigh a public benefit alongside shareholder interests, but do not provide for broader accountability.

-

We can bring ethics back to Professor Friedman’s call to corporate purpose by returning to the more inclusive purposes that historically bound us together to form corporations. Corporations have the capacity to tap humanity’s greatest potential to accomplish projects spanning, in scope and time, beyond what any individual could provide to the world. Think of the earliest forms of group associations that combined our efforts, from the Roman origin of our word for corporation, corpora (founded “around a common tie such as a common profession or trade, a common worship, or the widespread common desire to receive a decent burial”), through the intergenerational building of cathedrals erected to the glory of powers beyond ourselves...In theory, the 2019 Business Roundtable Statement demoting shareholder primacy, and describing corporate purpose as “a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders,” is a good start to rethink the direction in which we are headed. Recent work by Professor Lucian Bebchuk and Mr. Roberto Tallarita asks why, however, if corporations were serious about these changes, they did not bring them more often to their governing boards. Professor Tyler Wry’s work further suggests that Covid-19 is testing the resolve of the companies that signed the Statement. Since the economic impacts of Covid-19 began, its signatories have paid out 20 percent more capital to shareholders than similar companies, and signatory companies have been almost 20 percent more likely to announce layoffs or worker furloughs. Given management incentive systems in place, the Statement’s aspirations do not seem to be penetrating into the behavior of signatory corporations. As another essay by Bebchuk, Tallarita, and Mr. Kobi Kastiel examining the efficacy of stakeholder constituency statutes in this ProMarket series concludes, there should be “substantial doubt [about]… relying on the discretion of corporate leaders, as stakeholderism advocates, to address concerns about the adverse effects of corporations on their stakeholders.”

-

More companies are committing themselves to social change. Is it all talk?

September 29, 2020

When the Business Roundtable last August issued a statement on corporate purpose shifting from focusing on returns to shareholder to satisfying the needs of a broader range of stakeholders, it was treated as momentous news. But were the U.S. CEOs signing the statement serious? Would anything really change? Two academics decided to follow up, contacting the 184 companies where CEOs pledged their support, asking who was the highest level decision-maker that approved the decision – was it the board of directors, the CEO, or an executive below the CEO? Only 48 companies responded, and 47 said it was approved by the CEO, not the board. There’s no reason to believe the picture would be much different in the non-respondents, suggest the researchers, Harvard Law School professors Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita. And they argue the fact the boards weren’t involved indicates the CEOs didn’t regard the statement as a commitment to make a major change in how their companies treat stakeholders. “In the absence of a major change, they thought that there was no need for a formal board approval,” they report in a law school publication. Another explanation, of course, is that the CEOs believe the statement is what their corporations are already committed to. In his just-released book The New Corporation, UBC law school professor Joel Bakan writes about how companies have been trying to present a different face in recent years, more compassionate and committed to social ends. “Visit the website of any major corporation and you’ll wonder whether you’ve accidentally clicked on that of an NGO or activist group. These days all corporate communications lead with social and environmental commitments and achievements,” he notes. Whether this is driven by noble impulses, or an attempt to do well financially by doing good societally, or just blarney is up for debate. You, however, may be happier working for a company that is more socially and environmentally conscious, perhaps with a high-sounding purpose and even giving you time off for volunteer activity, as some companies do.

-

What is stakeholder capitalism?

September 18, 2020

“When did Walmart grow a conscience?” The question, asked approvingly in a Boston Globe headline last year, would have made Milton Friedman turn in his grave. In a landmark New York Times Magazineessay, whose 50th anniversary fell on September 13th, the Nobel-prizewinning economist sought from the first paragraph to tear to shreds any notion that businesses should have social responsibilities. Employment? Discrimination? Pollution? Mere “catchwords”, he declared. Only businessmen could have responsibilities. And their sole one as managers, as he saw it, was to a firm’s owners, whose desires “generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society”. It is hard to find a punchier opening set of paragraphs anywhere in the annals of business...Some bosses claim they can do this, keen to win public praise and placate politicians. But they are insincere stewards, according to Lucian Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel and Roberto Tallarita, of Harvard Law School. Their analysis of so-called constituency statutes in more than 30 states, which give bosses the right to consider stakeholder interests when considering the sale of their company, is sobering. It found that between 2000 and 2019 bosses did not negotiate for any restrictions on the freedom of the buyer to fire employees in 95% of sales of public firms to private-equity groups. Executives feathered the nests of shareholders—and themselves. Such hypocrisy is rife. Aneesh Raghunandan of the London School of Economics and Shiva Rajgopal of Columbia Business School argued earlier this year that many of the 183 firms that signed the Business Roundtable statement on corporate purpose had failed to “walk the talk” in the preceding four years. They had higher environmental and labour compliance violations than peers and spent more on lobbying, for instance. Mr Bebchuk and others argue that the “illusory hope” of stakeholderism could make things worse for stakeholders by impeding policies, such as tax reform, antitrust regulation and carbon taxes, if it encourages the government blithely to give executives freedom to regulate their own activities.

-

Milton Friedman’s hazardous feedback loop

September 15, 2020

In a famous article written 50 years ago this week, Milton Friedman argued ‘the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits’. The statement remains a lightning rod for the debate on ‘corporate purpose’ – whether public corporations should be managed just for the benefit of shareholders or for a broader set of stakeholders, including employees, suppliers and the community. We continue to go back and forth. In 2019, to much fanfare, 181 CEOs of the US Business Roundtable publicly committed to manage corporations for stakeholders – reversing their 1997 statement that upheld shareholder primacy! Not so fast, countered Harvard Law Professors Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita, who argued that stakeholderism can backfire in insulating corporate leaders from external accountability and compromising economic performance… to the detriment of broader stakeholders! Friedman’s essay was necessarily of its time. In 1970, Friedman was one of the leading economists of his day. However, and not really his fault, he presided over a discipline profoundly shaped by a reductionism that was then the deep guiding force of social sciences, but which has since revealed limitations. Economics was not alone in being so waylaid, but was arguably most affected. The extraordinary explanatory power of reductionism in the hard sciences over the preceding centuries had drawn all fields with scientific pretensions in the direction of physics and its methods. Social scientists were eager for their own simple, universalizable laws and for the prestige which might follow such discoveries. But, fifty years on, general laws in the social sciences remain elusive, and another development from the 1970s clarifies why. Even as Friedman was penning his op-ed, a new science – ‘complexity science’ – was emerging. It – and its associated ‘systems thinking’ – announced itself with the formation of the Santa Fe Institute in 1984.

-

The Illusory Promise of “Stakeholderism”: Why Embracing Stakeholder Governance Would Fail Stakeholders

September 9, 2020

An article by Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita: In The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governnace, which we will present at the Stigler Center’s Political Economy of Finance conference later this week, we critically examine “stakeholderism,” the increasingly influential view that corporate leaders should give weight to the interests of non-shareholder constituencies (stakeholders). Acceptance of stakeholderism, we demonstrate, would not benefit stakeholders as supporters of this view claim. Corporate leaders have incentives, and should therefore be expected, not to use their discretion to benefit stakeholders beyond what would serve shareholder value. Furthermore, over the past two decades, corporate leaders have in fact failed to use this kind of discretion to protect stakeholders. Our analysis concludes that acceptance of stakeholderism should not be expected to make stakeholders better off. Embracing stakeholderism, we find, could well impose substantial costs on shareholders, stakeholders, and society at large. Stakeholderism would increase the insulation of corporate leaders from shareholders, reduce their accountability, and hurt economic performance. In addition, by raising illusory hopes that corporate leaders would on their own provide substantial protection to stakeholders, stakeholderism would impede or delay reforms that could bring meaningful protection to stakeholders. Stakeholderism would therefore be contrary to the interests of the stakeholders it purports to serve and should be opposed by those who take stakeholder interests seriously.

-

The one certainty about the Business Roundtable’s “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation” is that it has elevated that topic to a new height in global policy debates. A year after the BRT announced its new view of purpose on Fortune’s cover, “stakeholder capitalism”—what it means, and what, if anything, should be done to advance it—is a hot issue, sparking hotly opposed views. As the U.S. election approaches, it will only get hotter. The BRT’s statement was prompted by JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon, who was then the BRT’s chairman, and was signed by 184 CEOs of major U.S. corporations... “The statement is largely a rhetorical public relations move rather than the harbinger of meaningful change,” say Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita of the Harvard Law School in a 65-page article, “The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance.” They argue that the incentives CEOs face have not changed, so their behavior won’t change. The authors also examine corporate behavior when state laws have permitted companies to protect stakeholders other than shareholders; they say they found no evidence that companies do so any more often than when they are not permitted to do so...Bebchuk and Tallarita argue more bluntly that CEOs and directors are seeking more power for themselves. “The support of corporate leaders and their advisers for stakeholderism is motivated, at least in part, by a desire to obtain insulation from hedge fund activists and institutional investors,” the authors say. “In other words, they seek to advance managerialism”—a system in which managers exercise the most power—“by putting it in stakeholderism clothing.” The BRT explicitly denies that its members want to avoid accountability.

-

Wednesday marks the first anniversary of the Business Roundtable’s vocal renunciation of “shareholder primacy” in a statement that claimed to “redefine the purpose of a corporation.” Like most efforts at “corporate social responsibility,” the initiative has proved long on public relations, short on action, and lacking in effect. Among the 181 CEOs who signed, Harvard Law School’s Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita have found only one whose board of directors gave approval. On the organization’s own website, the most recent “Principles of Corporate Governance” still dates from 2016. The Business Roundtable’s CEO members sought to ensure the public that they could be trusted as benevolent leaders of the economy, but instead they have demonstrated precisely the opposite — that multinational corporations are incapable of fulfilling obligations voluntarily to anyone besides shareholders, and external constraints are needed. In fairness, the market’s competitive pressures discourage any one firm from hampering short-term profitability for the sake of corporate actual responsibility. But that is precisely where an institution like the Business Roundtable could play a valuable role, were it genuinely committed to addressing interests beyond those of the shareholders who control the firms themselves.

-

An article by Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita: By putting American workers through months of turmoil, the Covid-19 crisis has heightened expectations that large companies will serve the interests of all “stakeholders,” not only shareholders. The Business Roundtable raised such expectations last summer by issuing a statement on corporate purpose, in which the CEOs of more than 180 major companies committed to “deliver value to all stakeholders.” Although the Roundtable described the statement as a radical departure from shareholder primacy, observers have been debating whether it signaled a significant shift in how business operates or was a mere public-relations move. We have set out to obtain evidence to resolve this question. To probe what corporate leaders have in mind, we sought to examine whether they treated joining the Business Roundtable statement as an important corporate decision. Major decisions are typically made by boards of directors. If the commitment expressed in the statement was supposed to produce major changes in how companies treat stakeholders, the boards of the companies should have been expected to approve or at least ratify it. We contacted the companies whose CEOs signed the Business Roundtable statement and asked who was the highest-level decision maker to approve the decision. Of the 48 companies that responded, only one said the decision was approved by the board of directors. The other 47 indicated that the decision to sign the statement, supposedly adopting a major change in corporate purpose, was not approved by the board of directors. We received responses from only about three-tenths of the signatories. Yet there is no reason to expect that these companies are less likely than companies electing not to respond to have obtained board approval for joining the statement.