For many lawyers who are also mothers, the more that things have changed in recent years, the more they’ve remained the same.

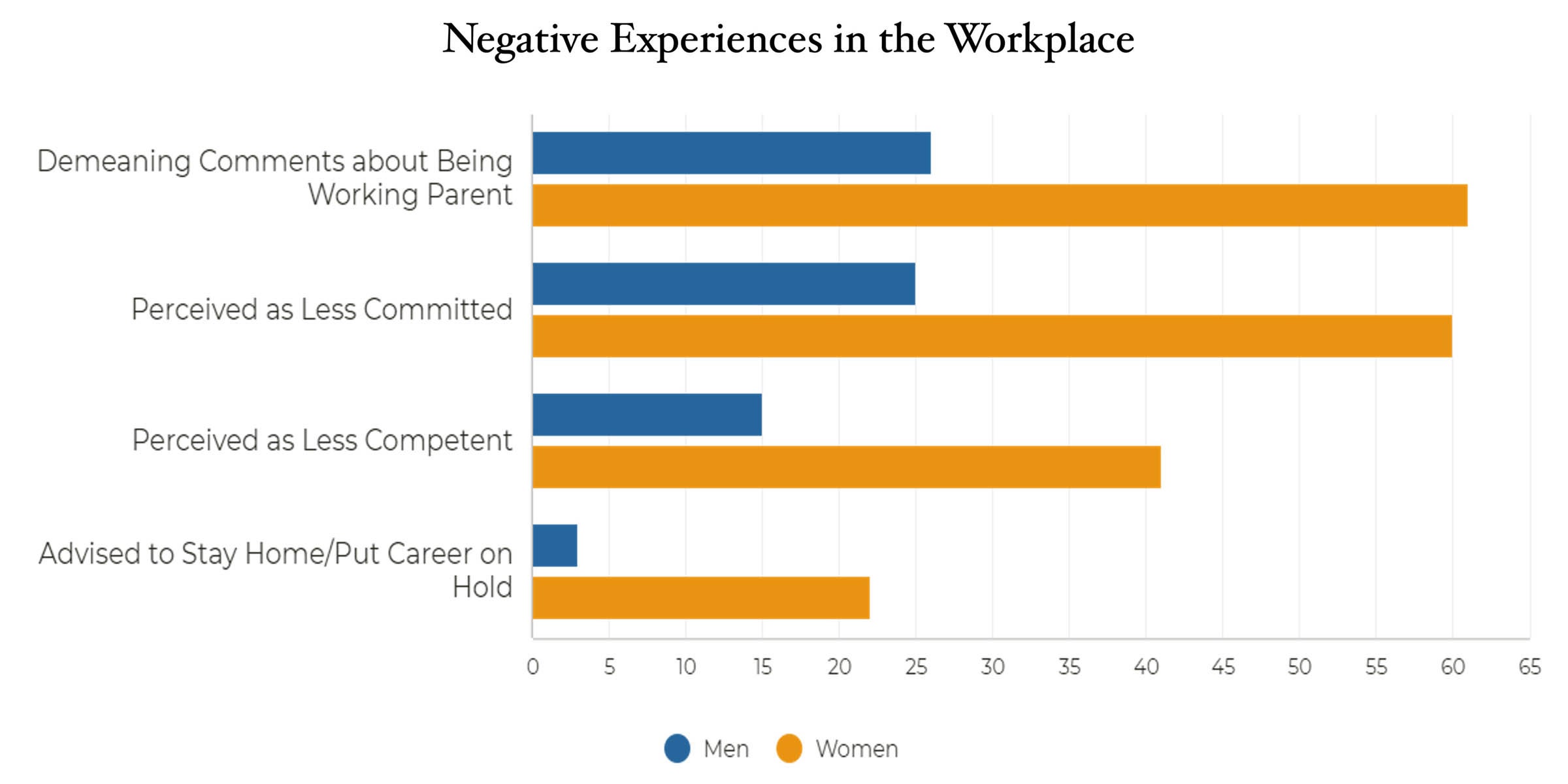

Mothers in the legal profession are much more likely to feel perceived as “less competent and less committed” than men with children or people without them, said Michelle Browning Coughlin, a member of the ABA Commission on Women in the Profession, during a recent panel discussion at Harvard Law School on “Parenting While Lawyering.”

Sixty percent of mothers working in law firm settings had this perception, she said, compared with only 25 percent of fathers, even though women have outnumbered men in law school for most of the last decade. The same disparities exist outside of law firms — in government, public interest, and other settings.

These were among the many findings illustrating parents’ “negative experiences at work” that are outlined in the 2023 American Bar Association report “Legal Careers of Parents and Child Caregivers.” Coughlin, who is also assistant professor and director at the Lunsford Academy for Law, Business + Technology at the Northern Kentucky University Salmon P. Chase College of Law, presented the report’s findings with Paulette Brown, former president of the American Bar Association and principal of MindSetPower.

David B. Wilkins ’80, Lester Kissel Professor of Law, and Jamie Wacks ’98, lecturer on law, moderated the discussion, which also included Hannah L. Kilson ’97, former president of the Boston Bar Association and a partner at Nolan Sheehan Patten, who shared her own reflections on parenting while lawyering drawn from her career working at a large law firm, in government, and now in a boutique private practice.

Taking action

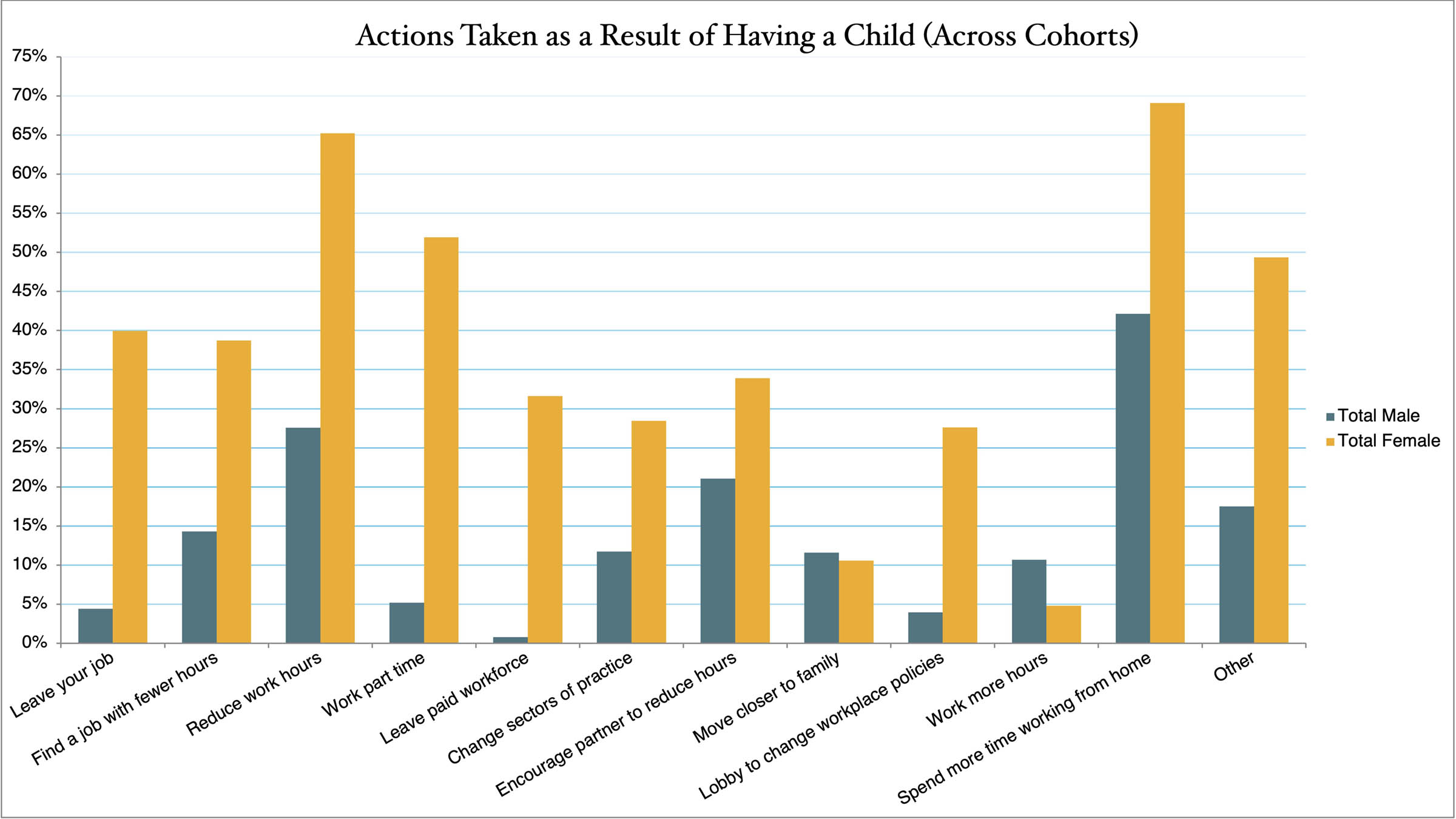

Illustrating how slow society is to change even when a workplace issue has been front and center for years, Wilkins opened the panel by referring to a 2015 career study of Harvard Law School graduates and a graph showing that 70 percent of women surveyed said they chose to work from home after having a child.

“When we did this survey back in 2010,” Wilkins said, “this had lots of consequences on the impact of women’s careers, including […] delays in promotions.” Women also changed sectors or left their jobs or the workforce altogether. It stands out, Wilkins said, that in most circumstances women were more likely than men to change their work circumstances — with one glaring exception. After having a child, many men surveyed began working more hours.

Having children, Wilkins said, had a number of effects on parents in the legal profession. Wilkins listed the effects: “people questioning their work or their effort, loss of income, loss of opportunity to travel, loss of challenging work assignments.”

Still, he pointed out, the audience of students will likely experience even more intense challenges in caregiving down the road. “We didn’t really look at being a caregiver of parents. … More and more of you are going to find yourself in that situation, as aging baby boomers like me live longer and longer. And therefore, the complexities of the squeeze that you guys are going to be under will increase,” Wilkins said.

‘The motherhood penalty’

Despite the fact that women now outnumber men in law school, women still face significant barriers juggling parenting and their legal careers, the panelists repeatedly made clear. Comparing data collected in Center on the Legal Profession’s 2015 career study to that gathered by the ABA in the last couple years shows how incremental progress has been.

Drawing from a survey of more than 8,000 lawyers and 10 focus groups, the ABA report illustrated the “motherhood penalty,” which women with children who work in the law and other professions still experience.

“Certainly, our career is not so different than other careers,” Coughlin pointed out. “And yet there are places where within the profession — particularly around billable-hour models,” she said, where the motherhood penalty can prove especially harmful.

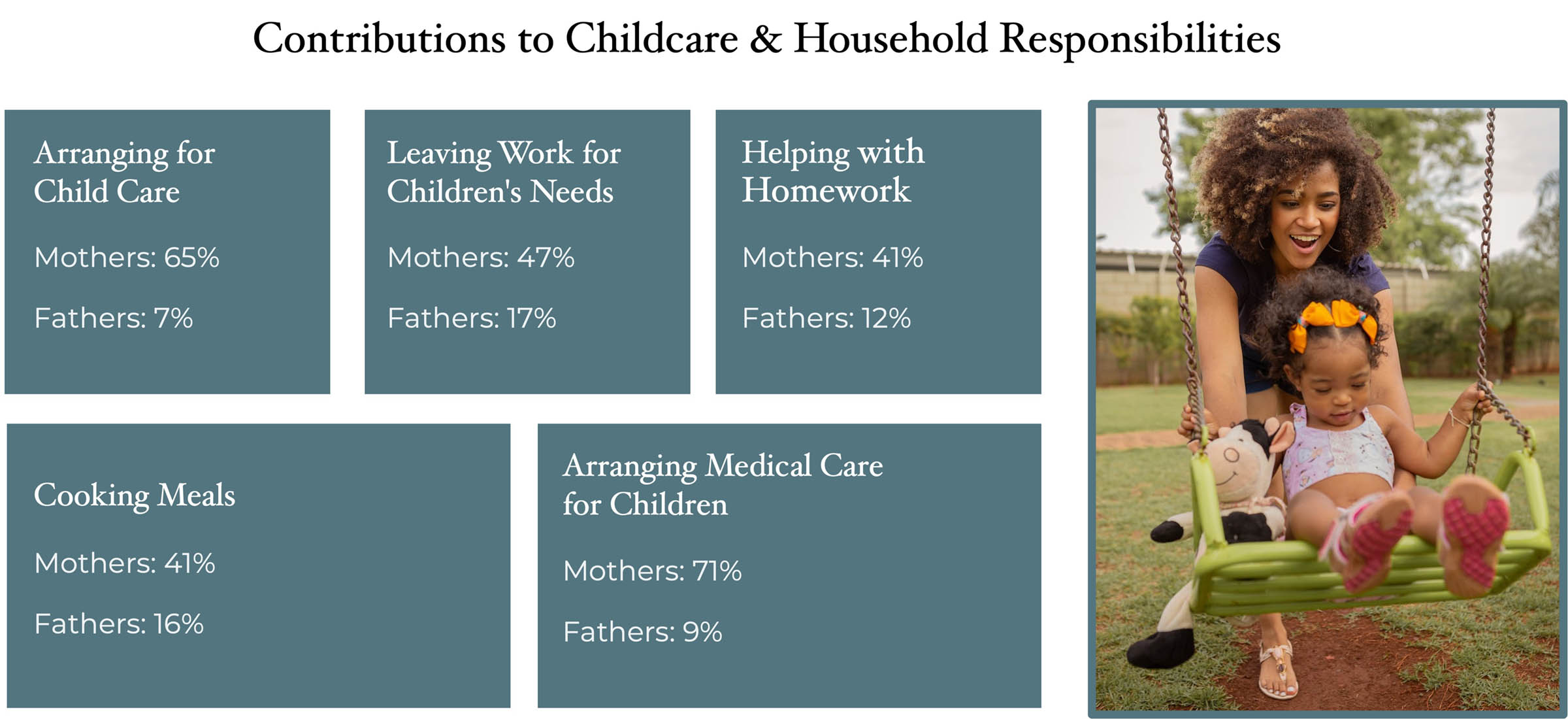

The billable hour, again and again, became the focus of conversation. Pointing to a slide showcasing the disparate contribution of mothers and fathers to childcare and household responsibilities, Coughlin emphasized the unsettling numbers. For instance, when it came to tasks like arranging for childcare, 65 percent of mothers surveyed shouldered the burden compared with 7 percent of fathers.

“There are only so many hours in the day,” Coughlin said. “If we see that women are doing a disproportionate amount of the labor [at home] … — the invisible labor, the unpaid labor, the mental load — … [then] there’s just naturally less time available to do billable hours.”

With 47 percent of mothers “leaving work for children’s needs,” she said, compared to 17 percent of fathers, “it just sets you up for not being able to compete at the same level.”

For Coughlin, gathering this data was personal. Pointing to a slide saying 70 percent of women surveyed felt they were “overwhelmed” or had “too much to do,” she recalled entering law school with a child and then having a second during her studies.

“When I came out of law school and went into a big law firm, I had two little kids at home,” she said. “And the feelings of guilt were so hard. And then that’s reinforced by these messages that you get that you’re not being a good enough mom and you’re also not a good enough lawyer. … The guilt is really difficult to manage at times and can put so much mental strain on you as an attorney.”

Cumulative disadvantage

The cumulation of these consequences, from parental guilt to difficulties at work, eventually leads to an overwhelming pay gap between women and men as well as challenges to women’s advancement, from missed work opportunities to difficulties finding sponsorship. Describing the additional ten focus groups that went into forming the report, Brown said that anecdotes from lawyers across the profession emphasized how the most marginalized often experienced the most disparate impact.

Brown, a single parent of adoptive children, said that single parents “prove themselves every day” by juggling the intense workload and sole responsibility of childcare.

“What was most insidious … is that women of color a lot of times have to do what I call ‘prove it again, prove it again,’” she said. “When you have this extra layer of being a parent, that’s something else. You have to also prove that I can be a parent, I can be a woman of color, and I can do this job no matter how many times I’ve done it before and show you that I can do it, I got to show you that I can do it again.”

She also noted that women of color are often tasked with lawyer “housework” like joining diversity committees, which typically don’t contribute to billable hours.

Focus groups also revealed that many lawyers changed jobs to seek more flexibility. Many women, Brown said, moved from firms into government roles. “They thought that switching from a law firm going into government would be easier, but it wasn’t necessarily easier because they were committed to being in their seat from 9 to 5.” One prosecutor in the focus groups shared that she was told she had to choose between her family and her job, Brown said.

Making change

When it comes to how to change the legal profession — and society more generally — panelists drew from the report for a variety of recommendations. The panelists encouraged legal organizations to implement family-friendly policies, offer comprehensive health insurance, and provide generous parental leave.

“When this report came out, it really spoke to my experience. I was very familiar and also very frustrated in some ways that we haven’t moved the needle very far,” Kilson said. She pointed to bar associations like the ABA and Boston Bar Association as important gathering places for lawyers frustrated with the status quo.

“We have the ability to bring together lawyers, engage in conversations, have groups, help our firms to develop policies that address some of these issues,” she said. “And I really think our associations are kind of an educational [center], but they’re also an advocacy space.”

Kilson advised the audience to ask, “What can you do as an individual?” and “What can you do as part of an organization?” She recommended open communication as a paramount strategy for navigating the unequal terrain. “Communicate with your partner” was shared alongside “communicate with your employer.”

Each panelist emphasized that students should not lose sight of their rising power. Closing the session, Wilkins asked the panelists: “How many reports have there been issued by the American Bar Association about the work-life family issue?”

Brown responded, “I’ve done three.”

“So why do we think today will be any different?” Wilkins asked.

“I think that the students who I interact with today are just not going to stand for it,” Coughlin said.

Kilson extended the challenge to those in the audience. “Exercise your agency,” she said. “Think about where you’re going. Send a message to the places where you’re not going.”

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.