One hundred years ago, in 1919, a German school of design addressed a crucial housing shortage. Led by founder Walter Gropius, Weimar’s Bauhaus school used industrial materials to create in Germany what it called “minimum dwellings,” functional and economical housing built in spare, modernist style.

Following World War II, American universities faced a similar shortage, as veterans returned to their studies. In 1948, Harvard Law School Dean Erwin Griswold ’28 S.J.D. ’29 turned to Gropius. He commissioned the architect, who had immigrated to the U.S. in 1937, to create the first Harvard graduate residence center, radically expanding what many saw as the Harvard style.

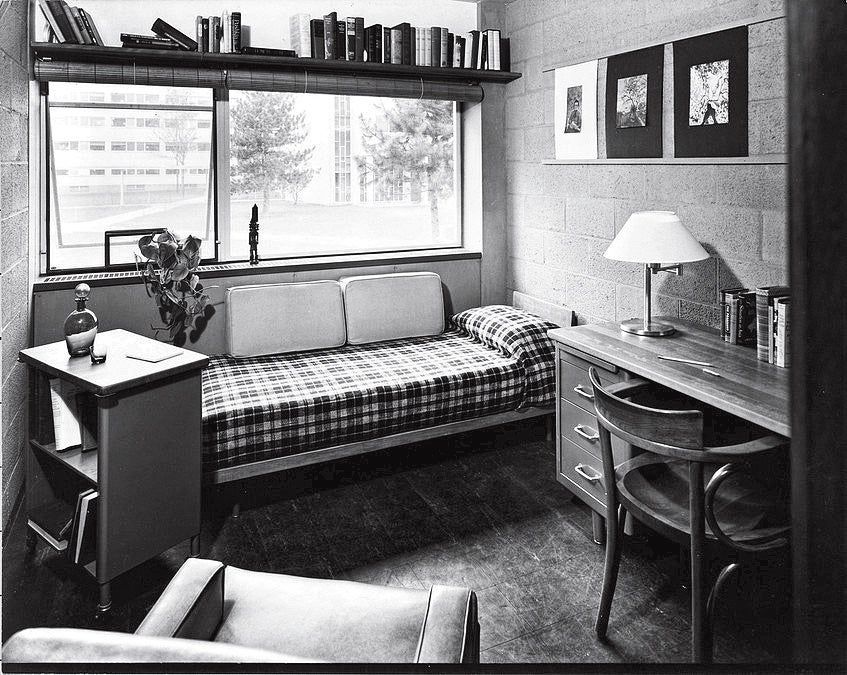

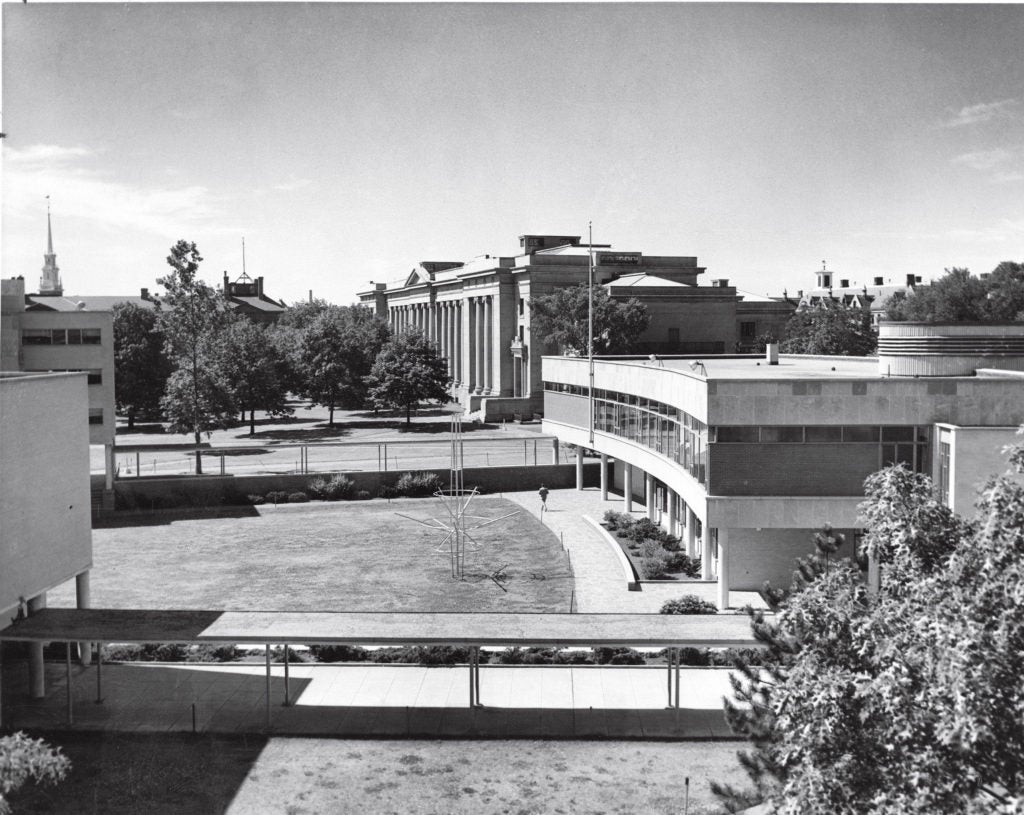

In what was then the law school’s largest fundraising campaign, $1.5 million was budgeted for the project: a complex (also funded in part by the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences) that would include a dining hall, a cafeteria, and lounge areas (for many years called the Harkness Commons and now the Caspersen Student Center), as well as shared outdoor space and seven dorms (two for GSAS students), all of which are still in use today.

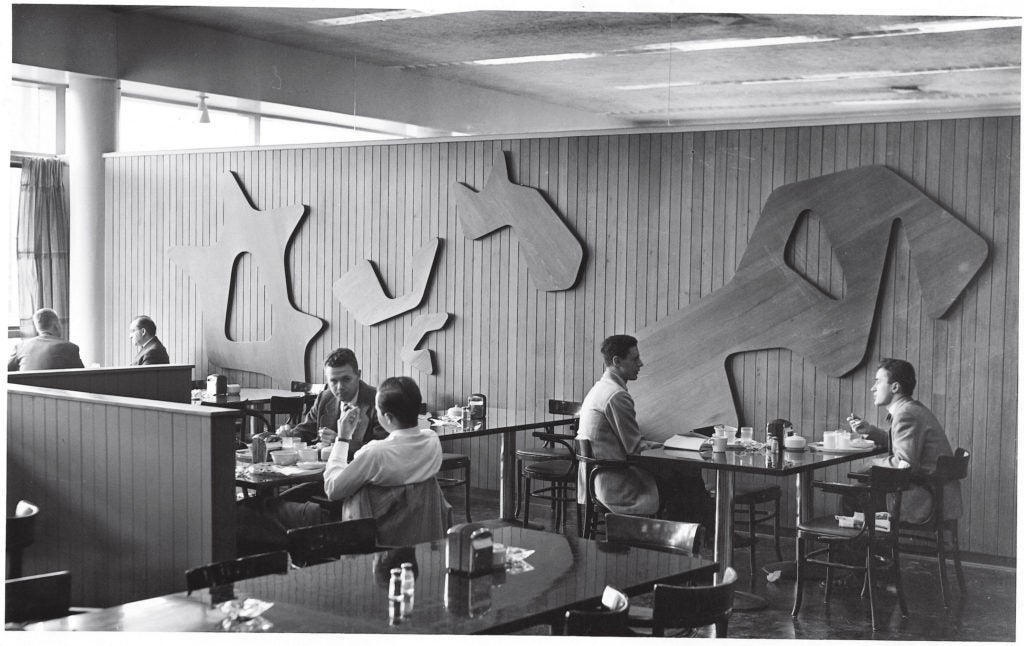

As part of the project, Gropius (who was teaching at the Harvard Graduate School of Design) insisted on a budget for art as well, commissioning site-specific works from an international roster of sculptors, painters, and textile artists, including Josef and Anni Albers, Hans Arp, and Gyorgy Kepes, as well as American Richard Lippold. Several of these artworks remain in place today, while others—including newly cleaned and restored works by Joan Miró and Herbert Bayer—are part of the exhibit “The Bauhaus and Harvard” at the Harvard Art Museums, Feb. 8 through July 28. An exhibit of Hans Arp’s “Constellations II,” which initially graced the HLS dining hall, coincides. (Another exhibit, “Creating Community: Harvard Law School and the Bauhaus,” will be on display at the HLS Library Caspersen Room, Feb. 4-July 31.)

Known simply as the Graduate Center when it opened on Oct. 6, 1950, Gropius’ complex stands as a turning point in American architecture, according to A. Melissa Venator, Stefan Engelhorn Curatorial Fellow in the Busch-Reisinger Museum, who is assisting on the Bauhaus exhibition. Even The New York Times noted the commission, with a story headlined “Harvard Decides to ‘Build Modern.’” The project lent the stark style the Harvard imprimatur, and marked a bold departure from the university’s traditional neo-Georgian, ivy-covered brick. “The spirit of the age required a certain spartanness,” says Alex Krieger, Graduate School of Design Professor in Practice of Urban Design. “A moving away from the overindulgence of 19th-century architects.”

Not everyone appreciated the broad expanses of concrete, however, even though the Bauhaus structure—with its emphasis on internal support, rather than external retaining walls—allowed for large windows that took in the shared public space. The New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable, for example, dismissed the center as “disappointingly pedestrian.”

Even today, students on their way to lunch, passing by such works as Josef Albers’ brick relief “America,” may not recognize the genius that transformed a simple building material into a masterpiece of negative space. “Is that art?” Harish Vemuri, a 2L, commented recently, when asked about the work in the Caspersen Student Center.

“It doesn’t read as an artwork,” explains Venator. That, she says, is part of the Bauhaus approach: “that art would surround you in an almost unconscious way.”

“Harvard has a history of art being integrated in its public spaces,” says Laura Muir, research curator for academic and public programs, who curated “The Bauhaus and Harvard.” The Caspersen Student Center, she says, “is the beginning of that in a systematic way, as a total project.”