Lloyd Weinreb ’62 retired as Professor of Law on July 1. Almost no one knew of Lloyd’s impending retirement. He did not tell his students. Although he had apprised the dean of his plans months earlier, he did he share the news with many colleagues. Characteristically, he wanted no fuss.

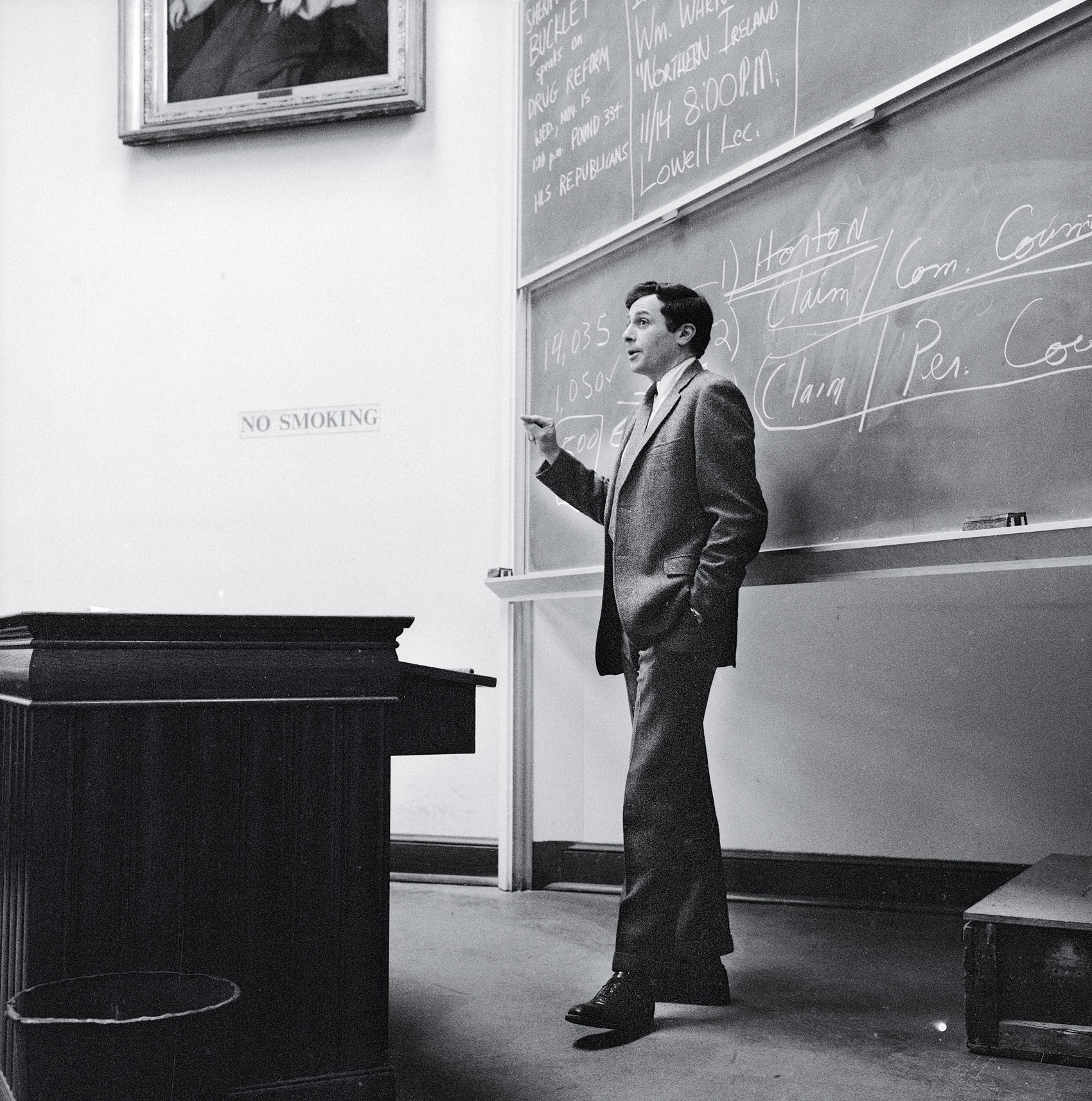

But Lloyd merits a fuss. Since 1965, he has served as a mainstay of the Criminal Law and Criminal Procedure curriculum at Harvard Law School. At some point in the 1990s, Lloyd began teaching Copyright, to challenge himself and help the school, and he promptly published a much-discussed article on the subject in the Harvard Law Review. He achieved a similar scholarly splash when his book “Legal Reason: The Use of Analogy in Legal Argument” came out in 2005.

Most important on the scholarly front, Lloyd wrote the magisterial “Natural Law and Justice,” published in 1987 by Harvard University Press. In that book, he explicated the ancient Greek idea of natural law as one of “normative natural order,” including assumptions not just about how things ought to be in the world, but also about how they are. A few years later, he followed up with the provocatively titled philosophical study “Oedipus at Fenway Park: What Rights Are and Why There Are Any” (1994).

Throughout Lloyd’s career, his teaching matched his scholarship. Indeed, as the author of “Oedipus at Fenway Park,” Lloyd, it could fairly be said, followed in the footsteps of Red Sox legend Ted Williams, who hit a home run in his last time at bat. Like the Splendid Splinter, Lloyd—according to reports from students in his final Criminal Procedure class—went out at the top of his game. He had lost nothing off his fastball. He had as many more innings left in him as he might have wanted to play.

Although I could wax on indefinitely with sports metaphors, candor requires a confession. I am quite sure Lloyd has no idea who Ted Williams was. For that matter, I doubt he knows the difference between the World Series and the Super Bowl. When Lloyd wrote “Oedipus at Fenway Park,” he had to ask me to give him the name of a Red Sox player who was conspicuously favored by natural fortune. (I suggested Roger Clemens—who, as it happens, has drawn subsequent accusations of abetting his natural endowments with regular injections of steroids.)

I might also add that I fear Lloyd would look scornfully on the triteness of my “going out at the top of his game” metaphor. In other writing, I have long relied on Lloyd, and shall continue to rely on him, to restrain me from inapt comparisons and rhetorical excesses. In this and other matters, I have benefited immeasurably from his friendship over a period of more than 30 years. In writing a tribute to him without soliciting his assistance, I feel the lack acutely (and fear that readers may pay the price). The retirement of a star almost inevitably diminishes the performance of the rest of the team, at least initially.

Lloyd and I initially bonded in friendship largely through long runs along the Charles River, when he was writing “Natural Law and Justice.” Conversation never faltered. Although spectator sports hold no interest for Lloyd, it has sometimes seemed to me that nearly everything else does. He loves literature and the arts, especially theater. (Lloyd serves as president of the Abbey Theatre Foundation of America.) He not only attends and reads plays, but also writes them (for his own amusement) in his free time.

Most mornings, Lloyd studies classical Greek. Yet, despite his literary and intellectual bent, he betrays no hint of self-satisfaction or stuffiness. (When President-elect Franklin Roosevelt called on the retired Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, and asked the justice why he had been reading Plato that morning, Holmes reportedly replied: “To improve my mind, Mr. President.” Lloyd says he studies Greek because it interests him.)

In both his professional life and his personal life, Lloyd has had an abiding sense of adventure.

Richard Fallon

In both his professional life and his personal life, Lloyd has had an abiding sense of adventure. Early in his teaching career, he took his young family to Colombia—the underdeveloped country, not the prestigious university—for a year to study the criminal justice system there. He still talks enthusiastically of other work that he has done assisting prison inmates struggling to rebuild their lives. He once collaborated with a police officer in writing a manual that gives plain-English instruction to other police officers on the rights of criminal suspects.

As I think about what Lloyd has brought to the Harvard Law School faculty for nearly 50 years, I cannot help lamenting that future students will miss his erudition, his practice-based insights, and his gift for blending practical with theoretical perspectives. They will miss him as a role model. They will miss the day-to-day example that he provides of the diversity of ways in which it is possible to think and live richly, both in the law and in life more generally.

The law school will also feel the loss of Lloyd’s contributions as an institutional citizen. Combining good taste with frugality, Lloyd picked out much of the artwork that adorns Areeda Hall and the law school tunnels. For many years, he has uncomplainingly chaired the Administrative Board, the school’s principal disciplinary body. (I’m sure no one has ever called or written him to express gratitude for being subjected to “dismission,” which is somehow a lesser sanction than “expulsion,” though that elusive difference sometimes has provoked hours of testy debate among faculty colleagues.) Earlier, he served a long stint on the Appointments Committee.

For Lloyd, however, I am delighted to project that life in retirement—apart from his absence from the classroom, of course—will remain largely unchanged. He will still arrive at his office earlier than nearly anyone else to study Greek, write fiction, and attend to correspondence. He will dispense advice to me and the other faculty members who regularly seek it. He will go to the gym every afternoon. He will keep up attendance at the theater and the opera. And he will maintain a travel agenda that includes a trip along China’s Silk Road, scheduled for this spring.

As always, Lloyd’s marvelous wife, Ruth—herself a scholar of French literature and a retired professor—will grace his home life with warmth, hospitality and vibrant conversation. Lloyd will spend more time with his children and beloved grandchildren. He will enjoy frolics with a just-acquired Labrador Retriever puppy.

Who knows? Lloyd may even have time to learn the difference between the World Series and the Super Bowl—though I suspect he will always look askance at my comparison of his last semester of teaching with a walk-off home run.

Richard Fallon is the Ralph S. Tyler, Jr. Professor of Constitutional Law at HLS.