There is no marker in Aníbal Bruno prison that speaks to home. In some cells, there are only dozens of men, sleeping on floors stained with feces, eating out of plastic bottles cut in half. But when he stands at the bars, Fernando Ribeiro Delgado pauses, as he would at the doorstep of any stranger’s house.

He offers a handshake to every man inside. He looks them in the eye. He calls each prisoner “Sir.” And though Delgado already has official permission to enter, he asks, because asking matters: Would it be all right if I came in?

“It’s the kind of respect that is obviously required, but that they are denied regularly by nearly everybody,” said Delgado, a clinical instructor in the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School.

Over the course of the years, as an expert on prison conditions in Brazil, Delgado has argued before the inter-American human rights system; negotiated with government officials; and nurtured relationships with prisoners’ families, prison officials, and members of the national press. But it all begins, for Delgado, in the cell blocks and hallways of Brazil’s most overcrowded prisons, listening to the people who live there.

Born in Brazil, fluent in Portuguese, Delgado has worked in these prisons for years, challenging his clinical students to think through the complications that come with mass incarceration and neglect. Inside Aníbal Bruno, they watch him closely: the calm, firm way he negotiates with officers for access; the undivided attention he gives to prisoners; the deference he shows to his local partners, whom he considers the undisputed experts in the rhythm of the place.

“I was really impressed to see him being so respectful, being so collaborative in his efforts, and not the Harvard professor who knows all,” said Colette van der Ven ’14. “He was a role model for so many of us.”

“Fernando’s work in detention centers in Brazil is unparalleled by anything being done by any clinic or NGO outside Brazil. He’s documented the most serious abuses in the most dangerous centers in the country.”

James Cavallaro, Vice Chair of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

Any praise that comes his way, Delgado deflects to his mentors, in particular his clinical professor, James Cavallaro, former executive director of the HLS Human Rights Program and current vice chair of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Over the years, Cavallaro has tracked Delgado’s career: Fearless, rigorous and dedicated are the words that come to his mind.

“Fernando’s work in detention centers in Brazil is unparalleled by anything being done by any clinic or NGO outside Brazil,” said Cavallaro. “He’s documented the most serious abuses in the most dangerous centers in the country.”

José de Jesus Filho, a Brazilian human rights lawyer, saw the potential when Delgado was an HLS student investigating the high-profile prison and police violence that hit São Paulo in May 2006. Delgado kept at it until 2011, when the HLS clinic released a joint report that exposed widespread police corruption and, according to de Jesus Filho, changed the way the Brazilian public viewed the sequence of events.

To de Jesus Filho, who monitored prisons for 20 years with Pastoral Carcerária (Catholic Prison Ministry), that kind of commitment stood out.

“When Fernando starts with something, he goes to the end,” he said.

In the field of prison rights advocacy, litigation before the inter-American human rights system is a powerful tool. When the court orders emergency measures, it binds all levels of government to the promise of protecting the life, safety and health of the persons at that facility. This, in turn, triggers a system of monitoring and reporting.

One of the clinic’s closest partners, Justiça Global (Global Justice), was at the forefront of this litigation, helping to secure protective measures at Urso Branco, one of the country’s most notorious prisons, back in 2002. It’s a case Delgado worked on as a fellow with Justiça Global and is still litigating today.

The work on Aníbal Bruno began years later, when a group of Brazilian rights organizations looked at mass incarceration patterns across the country and found another focus: the state of Pernambuco, where a new policy provided bonuses to police for every arrest they made.

Soon enough, they honed in on Aníbal Bruno, one of the largest prisons in Latin America, and among the most abusive. Since then, the clinic has worked with Serviço Ecumênico de Militância nas Prisões (Ecumenical Service of Advocacy in Prisons), Justiça Global, and Pastoral Carcerária to secure precautionary measures for all persons at Aníbal Bruno—including prison staff and the families of prisoners.

“I like this word Fernando uses: coalition,” said Wilma Melo, of Serviço Ecumênico de Militância nas Prisões, a longtime advocate and the family member of a former prisoner. “Each step we take, we take it together, and I believe this is the strength of our work.”

Years of monitoring have led to clear wins: a camera ban lifted, a punishment cell dismantled, medical help for the critically ill. Hundreds of illegally detained prisoners have had their cases reviewed and then have been released—including a forgotten man who was kept incarcerated 10 years beyond his original sentence.

But for every individual violation reported and remedied, there are thousands more. In a prison designed for 1,819 men, the population recently hit 7,000. At best, there might be one officer on shift for every 100 prisoners.

In a prison designed for 1,819 men, the population recently hit 7,000. At best, there might be one officer on shift for every 100 prisoners.

With so few officers on duty, gangs of prisoners take on, or are given, the power of policing. Their leaders, known as “Chaveiros” or “locksmiths,” have keys to the cells and use them to govern an economy of beds, forcing payment from anyone who wants a designated space to sleep. On Delgado’s first visit to Aníbal Bruno, he met with a Chaveiro whose personal cell was furnished with a full-sized mattress and a meeting table. A cellphone lay on the tabletop. A knife hung from his belt.

“It’s chaos,” said de Jesus Filho.

At the very least, advocates say, the monitoring has forced a kind of reckoning on prison officials. They’ve gone from denying the depth of the problems at Aníbal Bruno to acknowledging many of them, and working with others to address them. This may be why, at one public meeting, a representative from the prison officers’ union put the question to the clinic and its partners:

“Can we get precautionary measures for every other prison in the state?”

***

When Delgado, his students and his partners walk through the entrance to Aníbal Bruno, they hear the same thing every time. First, the call goes out, from one cell to another: “Human rights!”

Then come the arms, reaching out from behind the bars, too many to count: “Over here!” “Over here!” “Over here!”

Some days, the team will interview more than 100 people. The students will pair off with Delgado and then settle into a space the prisoners have cleared for them. In the presence of women, some prisoners will put on their shirts. They’ll offer what water they have on hand. And then the stories will start.

Months of picking through international law could not have prepared James Tager ’13 for the pressure. At one point, he took down all the details that made up one man’s story and then realized, as he was leaving the cell block: He had forgotten to ask for the man’s name and ID number.

“It’s not like you can call back next week and double-check the facts,” said Tager, who later got the man’s name. “I was literally shaking—this idea that after talking to someone, because I hadn’t gotten his name, he wouldn’t be helped.”

The learning for students is intense, said Clara Long ’12, who now visits detention centers as an immigration and border policy researcher with Human Rights Watch. She trained under Cavallaro and Delgado, working with them on the Urso Branco case.

“You have a very compressed time period to build trust with someone, figure out how to keep them safe while they’re talking, figure out the right questions and get the most accurate information possible,” said Long.

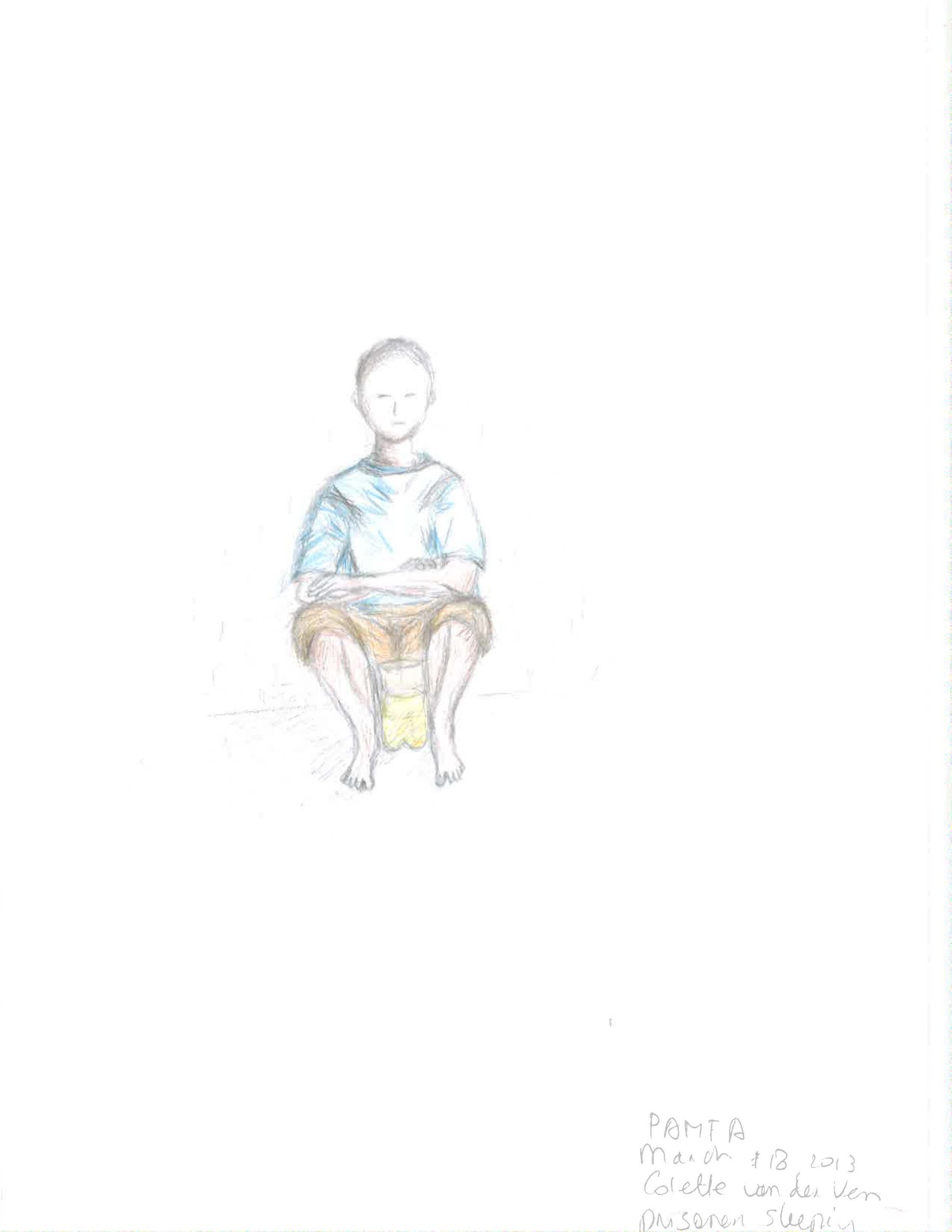

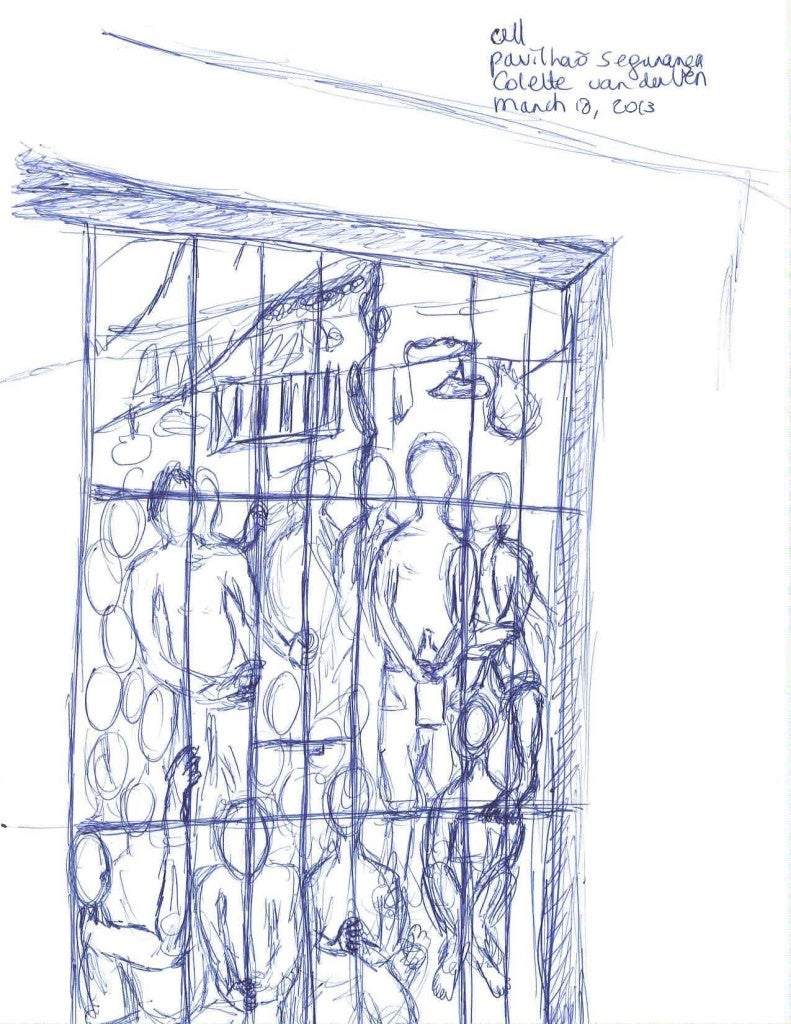

Nerve-racking is a good word for it. Before going through the metal detectors, van der Ven took a picture of a badly beaten man, only to hear a prison official’s warning about the camera ban inside. The ban had been in place for months, but there, in the moment, Delgado had an idea: Can anyone here draw?

Van der Ven had taken a few art classes in high school. That was enough.

“Just draw what you see,” he told her.

As she sketched a warehouse where hundreds of men ate and slept, some of the prisoners organized themselves so she could better see the space. Others gathered around, looking over her shoulder.

“It was like a unifying moment,” said van der Ven, now an associate in trade litigation at Sidley Austin. “We were all working toward justice for them.”

When the prisoners spotted a friend of theirs in her sketch, they joked that he was headed to the U.N. Instead, the coalition presented a slideshow of the sketches during a public hearing with the prosecutor’s office. The next time the team visited Aníbal Bruno, the camera ban was no longer in place.

There are many days when the question comes to Delgado’s mind: Are we making a difference?

Sometimes, the answer is clear and yes. Last spring, in response to repeated concerns the coalition raised, the court ordered a ban on strip searches of prison visitors. Several months later, prison administrators had passed their own statewide ban.

Number of people affected: 30,000 families every week.

But in prison work, there are constant reminders of the limits of legal advocacy. Recently, after the coalition created an online archive of thousands of pages of evidence, the state put the camera ban back in place.

So Delgado tries to remember: Small victories matter. The human barrier he forms with his students and partners, so that a prisoner suffering knife cuts can talk to medical staff privately, without the scrutiny of an officer. The extra time a team stands by the gate of the warehouse, refusing to leave until each prisoner gets bread they’ve been denied.

With their actions, they are undermining injustice in the moment. They are sending a message to all who are watching that every person is equal—deserving of dignity, protection and privacy.

“It’s not enough to report on the problems,” said Melo. “You have to make an impact there in the moment in order to produce the change.”

***

Take cell number 5. Melo had reported it before: a tiny, dank punishment cell, where Chaveiros would dump prisoners they had beaten. A long metal sheet was welded to the bars of the cell, perforated with small holes for air and light.

“The only thing comparable would be hell,” said Celina Beatriz Mendes de Almeida LL.M. ’10, who trained under Delgado and went on to become a professor at the Fundação Getulio Vargas School of Law’s Human Rights Clinic in Rio de Janeiro.

The team interviewed the 16 men inside, photographed their injuries, took down their names and then walked to the warden’s office, where Melo announced that she had “discovered” a punishment cell.

Nearly an hour later, after the prisoners had been removed, the warden stood in front of it, surrounded by a gang of Chaveiros, their arms folded across their chests. Hundreds of prisoners watched in silence behind them. Melo had insisted the metal door come down.

The warden examined it again, then finally turned to a nearby prisoner, and ordered him to find a tool that could remove it.

From somewhere in the crowd of prisoners, there came a suggestion: “A hammer?”

Yes, Melo said, a hammer. And so it came to be, that late one October afternoon, in one of the worst prisons in the country, the warden called for a hammer, and a prisoner proceeded to swing it, and together they brought the metal door down.

Even now, it is hard for Delgado and Melo to describe the emotion of the moment. To comprehend the ripple effects it had—for the prisoners, the warden, the Chaveiros, and beyond.

It was not the kind of victory that would make the newspaper. But it spread the spirit of possibility within the system, so that years later, when a prisoner told Melo about another punishment cell, he asked her to dismantle it, just like she did with cell number 5.

***

Since this article was written, the Inter-American Court on Human Rights has taken the rare step of summoning the state of Brazil to a public hearing on Aníbal Bruno. That hearing, on Sept. 28, will be broadcast live from Costa Rica here.