Last Monday, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov signaled that a diplomatic solution to the standoff between the former Soviet hegemon and western nations over the future of Ukraine might still be possible. But after months of failed talks and with more than 100,000 Russian troops still encircling its Eastern European neighbor, what negotiating strategies can the U.S. and its allies employ to defuse the crisis?

To find out, Harvard Law Today asked Rachel Viscomi ’01, director of the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program and a clinical professor of law, who has advised many Fortune 500 companies and co-teaches the course Advanced Negotiation: Multiparty Negotiation, Group Decision Making, and Teams. In an email conversation, Viscomi said that presenting a united front is one of the West’s key challenges, and that Russian President Vladimir Putin has already been “resoundingly successful” at sowing divisions among the allies and their peoples.

Harvard Law Today: Some commentators believe that President Putin has already won by forcing the U.S. to the bargaining table. In a negotiation, if one side manufactures a crisis, is there a risk that, by engaging, the other party encourages further bad behavior? In other words, does negotiating with hostage takers encourage further hostage taking?

Rachel Viscomi: To some degree, yes, that is always a risk. In the classroom, we often say that you teach others how to negotiate with you through your interactions with them. If they scream and shout and you cave, they’ve learned that screaming and shouting is an effective strategy when dealing with you. If you make concessions in response to threats, you should expect more threats. Of course, this is a more sophisticated setup than a classic hostage scenario. If I hold a gun to the head of a bank teller and you give me the money, my ploy worked. If you don’t give me the money, taking the bank teller’s life has no real value to me. In Russia’s case, though, the threatened invasion of Ukraine is more than just instrumental. Reestablishing Russian control over Ukraine has independent value to Putin.

HLT: What do you think of President Putin’s negotiating strategy?

Viscomi: Putin has spent years laying the groundwork for this moment in a way that is really paying off for him. He has the advantage of having been president continuously since 2012 (and having held power continuously since 1999). He has systematically accumulated a large cash cushion in order to minimize the impact of potential sanctions. He has deployed a strategic messaging campaign to build internal support. He has annexed Crimea and supported separatist movements in Donbas and Luhansk. And he has pursued an extended (and extremely effective) cyber strategy to divide and weaken the U.S. and other western targets. This last piece has been resoundingly successful. It would have been truly shocking to see conservative pundits spouting Russian talking points a decade or so ago. These days, someone like [Fox News commentator] Tucker Carlson carrying Putin’s water ceases to surprise. In many ways, this is the culmination of Putin’s long game. Having sown and watered the seeds of polarization, he’s now harvesting. And as Lincoln famously said, “A house divided against itself cannot stand.”

From Putin’s perspective, he has all the corners on the tic-tac-toe board. We can block one or two of his paths to three-in-a-row, but any of three outcomes will help him achieve his goals.

From Putin’s perspective, he has all the corners on the tic-tac-toe board. We can block one or two of his paths to three-in-a-row, but any of three outcomes will help him achieve his goals. Either: 1) this gambit serves as leverage to win him concessions in international negotiations that begin with his premise that the security architecture of Europe should be restructured to offer Russia greater security; or 2) Russia invades and conquers Ukraine, regaining territory he sees as culturally and strategically important as well as reestablishing Russia’s position as a power to be reckoned with; or 3) Russia simply holds the threat of invasion credibly and long enough to wreak havoc on the Ukrainian economy, expose and aggravate fault lines in the U.S./European coalition and NATO alliance, weakening their ability to work together and strengthening his hand in the short and longer term. The combination of careful advance work and the fact that his success case is so varied make this a really formidable strategy.

Putin can definitely overplay his hand, though. A failed invasion would be catastrophic for him, and maintaining military readiness over an extended period of time is costly, especially if you have cracks in your internal support.

HLT: How about the West’s approach to negotiations?

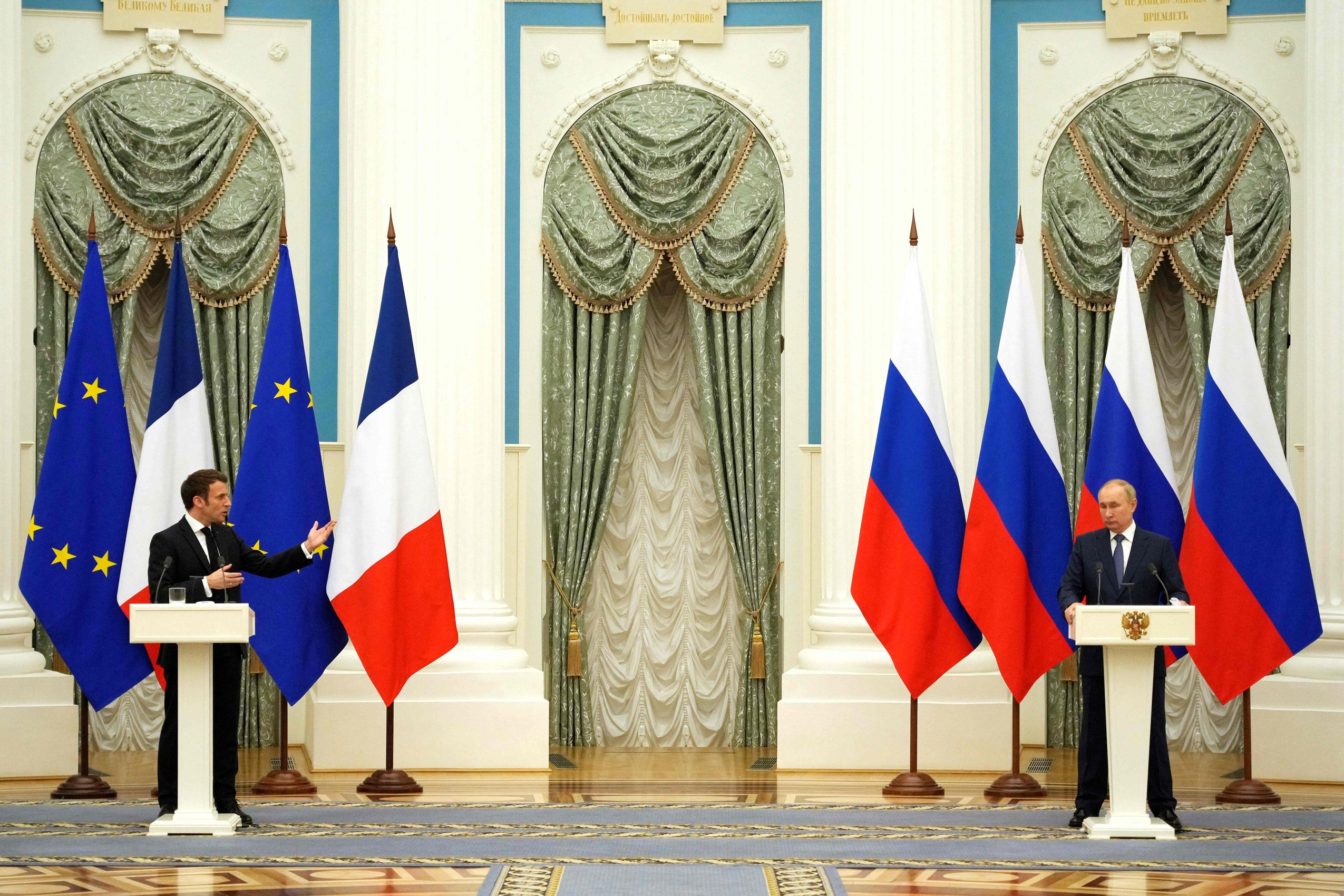

Viscomi: Obviously, democratic governments operate with different constraints than autocrats. Unlike Putin, who has been able to design and implement a plan over the course of decades, the U.S. and its allies don’t have that advantage. Power turns over more frequently in democracies, and many of the European leaders are relatively early in their tenure or, in the case of [French President Emmanuel] Macron, about to stand for reelection.

President Biden has spoken strongly about the swift response that invasion will provoke. The West needs to think really carefully and collectively about what sanctions they are willing to implement. The impact will be felt well beyond Russia, so it’s important to ensure we can stay the course. Sanctioning Putin and his inner circle will require something different of the global community than cutting off access to SWIFT [Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication].

The U.S. has been playing offense by declassifying intelligence in an effort to stay a step ahead of Russia and to neutralize the threat of a pretextual invasion. There are risks with that strategy, of course, including that your intelligence might be wrong or that you might compromise your sources. That said, it seems reasonably effective so far. And it may be exploiting some of the cracks within Russian society. Notably, Leonid Ivashov, chairman of the All-Russians Officers’ Assembly, recently called for Putin’s resignation, suggesting that the move toward war is merely an attempt to distract attention away from the dire situation in which the Russian people find themselves as a result of his mismanagement and kleptocratic regime. This is notable in part because Ivashov is not a liberal — he’s a hardline nationalist.

HLT: Ukraine has played down the risk of invasion and Germany hasn’t committed to the same level of sanctions as the U.S. How does it affect one’s negotiating position when not all one’s allies appear to be on the same page?

Viscomi: This is one of the challenges of trying to hold together a coalition of people with different constituencies, different interests, and different risk preferences. If all these conversations were happening behind closed doors, it wouldn’t be as much of a concern. “Acoustic separation” — the practice of calibrating your message differently for different parties in order to address their key interests and maximize the likelihood of bringing different parties on board for different reasons — would make a lot of sense here in the abstract, but is virtually impossible when we are so readily able to access reporting and videos from across the globe.

This is the culmination of Putin’s long game. Having sown and watered the seeds of polarization, he’s now harvesting.

While it would be ideal for Ukraine to preserve a sense of calm both to protect the populace and their economy, and for the U.S. to sound the alarm in an attempt to rally Germany to take a stronger stance and preempt Russia’s plans, message nuancing is all but impossible with a public negotiation strategy. Today, I can click a link to a Ukrainian newspaper and have it translated into English instantaneously. And this all plays to Russia’s benefit. One of Putin’s most practiced skills is fomenting division, and the more he can drive a wedge into the coalition, the weaker we look and the stronger he seems. Some of the most important work here needs to happen with coalition partners behind closed doors.

HLT: Germany and other European nations would be affected more directly by a conflict with Russia than would the U.S. How do parties who face different risks from a common threat forge a common negotiating position?

Viscomi: Carefully. It’s important to think about the ways those differences create challenges, but also the ways they present opportunities. You want to be as thoughtful as you can about ensuring your partners’ needs are met in a way that will keep them in your coalition. We saw that Biden and our allies tried to quickly identify and arrange to divert as much natural gas as possible to Europe to try to ensure the threat of sanctions was credible in the event that Russia invades. That was an effort to make it easier for coalition partners to make an agreement work. (Arguably it would have made even more sense not to have lobbied against sanctions on the Nord Stream 2 pipeline in the defense bill.) The key is that, to the extent possible, anything that is a problem for one coalition partner needs to be a problem for all the coalition partners. Without communication, trust, and shared problem-solving, it’s very hard to hold a disparate coalition together.

HLT: How would you advise Putin to proceed to get what he wants from the negotiations?

Viscomi: I wouldn’t advise him on that. My own view is that Putin needs to reckon with the fact that the world has changed and that his irredentist plans have no place in today’s world. Given that, I don’t imagine he’ll be seeking my advice any time soon.

HLT: How would you advise the U.S. and its allies to get the most out of the ongoing negotiations?

Viscomi: I think the U.S. needs to focus most of its efforts on behind-the-table work — close coalition building and joint understanding with allies to ensure an ironclad commitment to follow through on whatever consequence you promise. The stronger the coalition is, the better likelihood we have of threading the needle here. I don’t see any path to negotiating success on the U.S. side that does not come through collaboration and collective action.

And while this is so much easier said than done, I think one of the most critical things the U.S. can do is to help people understand that we have been strategically pitted against each other and that our division is playing into Putin’s hands. Until we can get past the disinformation and tribalism that prevent us from seeing that our shared national interests transcend party allegiances, we’re an easy mark.