Without mincing words, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy disparaged the American criminal justice system on Thursday for the three prison scourges of long sentences, solitary confinement, and overcrowding.

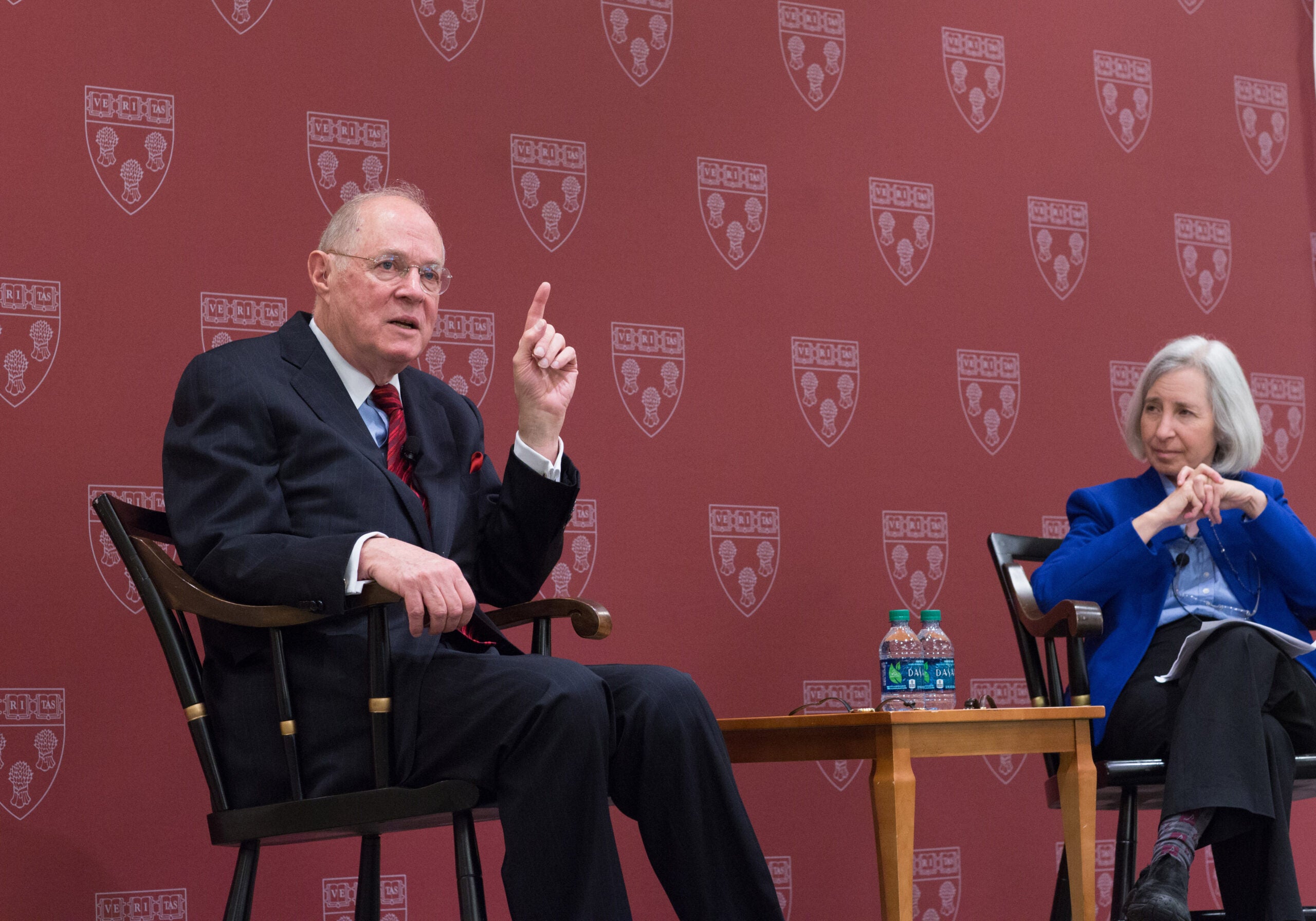

“It’s an ongoing injustice of great proportions,” said Kennedy during a conversation with Harvard Law School Dean Martha Minow at Wasserstein Hall, in a room packed mostly with students.

Kennedy criticized long prison sentences for the high costs associated with them. (In California, where Kennedy comes from, the cost per prisoner is $35,000 per year, he said.) He also said long sentences have appalling effects on people’s lives.

Solitary confinement, he said, “drives men mad.” He called mandatory minimum sentences “terrible” and in need of reform. Sentences in the United States, he said, are eight times longer than sentences in some European countries for equivalent crimes. With more than 1.5 million prisoners in federal, state, and local jails, the United States has the world’s largest prison population.

The worst of the matter, he said, is that nobody pays attention to this wrong, not even lawyers. “It’s everybody job to look into it,” he said.

Kennedy, LL.B. ’61, whose views on the court reflect a preoccupation with liberty and dignity, has often been described as the high court’s swing vote on major issues. But during his talk with Minow, he said he hated to be depicted that way.

“Cases swing. I don’t,” he quipped, as the room erupted in laughter.

A moderate conservative, Kennedy has sided with the court’s four liberal justices on social issues. The other four justices tend to be more conservative.

Appointed an associate justice on the court by President Ronald Reagan in 1988, Kennedy has written the majority opinion on many of its close decisions, such as in the historic ruling that made same-sex marriage legal across the United States.

He also cast the deciding votes in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which upheld the right to abortion even with new restrictions; Boumediene v. Bush, which extended the writ of habeas corpus to Guantanamo Bay detainees; and Lawrence v. Texas, which struck down the state’s sodomy laws.

When a student asked Kennedy what case he would like to be remembered for, he said he didn’t know the answer yet.

“I hope time will be a gracious judge,” he said.

Displaying a self-deprecating sense of humor, Kennedy said he recalls the cases he studied at HLS better than the cases he has heard as a justice.

Explaining how he makes his decisions and writes his opinions, Kennedy said he always asks himself the question: How he can be a good judge every day? The law, he has said, has a moral foundation, and it’s important to ask not only what the law is, but what the law should be.

“The law is discipline, ethic, philosophy, and commitment,” he said.

In addition to his court duties, Kennedy teaches law abroad, and that experience has been crucial to his views about the importance of the rule of law and the U.S Constitution.

“As you move eastward outside the United States, the law becomes more remote and authoritarian,” he said. “In the United States, the law is a promise. If you commit to an ethical course of conduct and be a good citizen, you’ll be free.”

In Poland, he was struck by students’ interest in and knowledge of American law. In China, he was bewildered when many students there said they wanted to go to law school.

“Many students said they had been influenced by movies,” he said. “I thought they had seen ‘Twelve Angry Men,’ but it was ‘Legally Blonde,’ which I had never heard of. I saw it afterwards. It’s a pretty good movie.”

When asked about his favorite professors at HLS, Kennedy mentioned Clark Byce, Ben Kaplan, and Donald Turner. Of the justices he looks up to, he said he admires Earl Warren and Hugo Black.

On to getting along with his colleagues on the bench, Kennedy said it’s easy.

“As a lawyer, you’re trained to disagree.”

This article was originally published in the Harvard Gazette on October 22, 2015.