Today, the power and language of human rights are ubiquitous. But this was not always the case, even a scant two decades ago. This is an idiom whose ubiquity is the direct result of a select few men and women who have dedicated their lives to its propagation. There is no doubt in my mind that Henry Steiner must be counted among them. Because of his singular vision and dedication, the Human Rights Program–now a leading forum in the field–has transformed legal education at Harvard Law School.

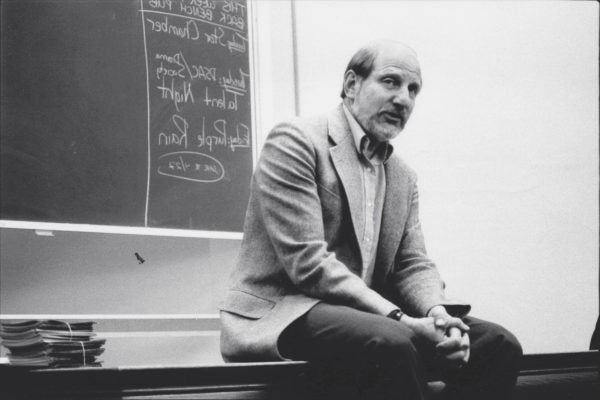

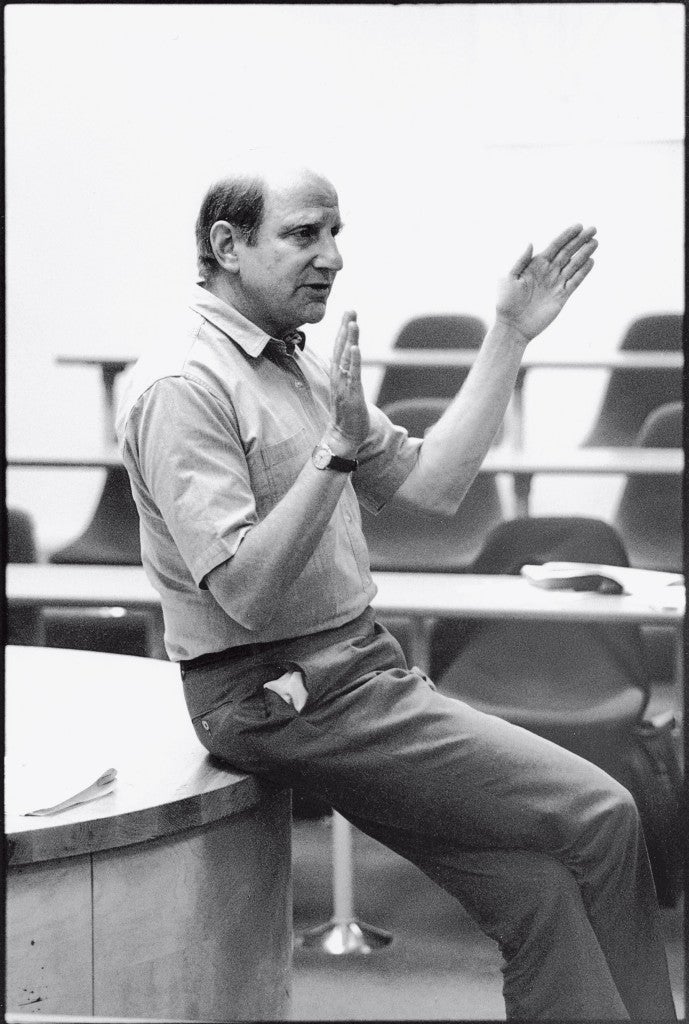

I first met Henry in 1984, the same year that a sketch of a human rights program was barely off the drawing board. Little did I know that this Harvard professor with a patrician bearing would carve out a significant niche at the law school for arguably the most critical idea of the modern era. But he did so, and with such a powerful imprint that it is impossible to imagine the law school today without HRP.

Henry believed, almost from the start of the program, that since human rights involves a language of power–of material for battle by the powerless–its legitimation in hallowed institutions was essential to its success. But he also knew that such a program in the academy had to meet exacting standards of excellence. That is why he emphasized HRP’s academic mission. It was on this pillar that all the program’s activities were built: coursework, research, internships, speaker series, visiting fellowships, clinical work, and the Harvard Human Rights Journal. Henry correctly believed that HRP was above all a place for academic inquiry.

“Henry challenged his students to understand human rights as a discipline and to dare question its orthodoxy.”

As a teacher, Henry challenged his students–myself included–to understand human rights as a discipline and to dare question its orthodoxy. Although he holds fast to its humanist and political ideals, Henry has never taught human rights as a religion. Even so, he has often revealed a belief that, far from being an antidote to human catastrophes, the study of human rights can offer a glimpse of the good society. It is this duality of the believer and the skeptic that has allowed Henry to mentor a wide and diverse college of students. These range from the most bracing Third World critiquers of human rights discourse to the most unabashed advocates of the ideology of human rights.

Henry’s book written with Philip Alston, “International Human Rights in Context: Law, Politics, Morals,” captures the open texture with which he approaches human rights. There are no sermons in it. Instead–and this is why I think the book will long remain the standard–he refuses to succumb to the mentality that the classroom is a congregation, and the law school a church. There is much to stir the mind of the idealist and to inspire the student to reach for a higher human intelligence. To achieve that combination is both Henry’s enigma and enduring identity.

Henry has a seductive mind and the wit of a comedian. But his penchant for excellence is unparalleled. Although he has been a mentor of mine–and I credit him with a selfless guidance of my career as a law professor and human rights scholar–he has never himself ceased to be a student. This is one of his most admirable proclivities. He is forever learning, pushing himself to understand other cultural milieus, to better comprehend the complexity of our universe. In August 2003, at an international conference on a truth commission in Nairobi, Kenya, he seemed to learn as much as he gave back. I know this will not change.

HRP would not have been possible without the foresight, commitment, and hard work of this deeply complex man. He took a possibility and made it into a reality. There is nary an important human rights institution across the globe that is not inhabited by a person who has been touched by Henry or HRP. That legacy can only grow further, even as HRP enters a new phase. In the academy, he leaves a more expanded political space in which the voices of dissent are less likely to be viewed as wild and dangerous. He has legitimized the difficult question in human rights circles.