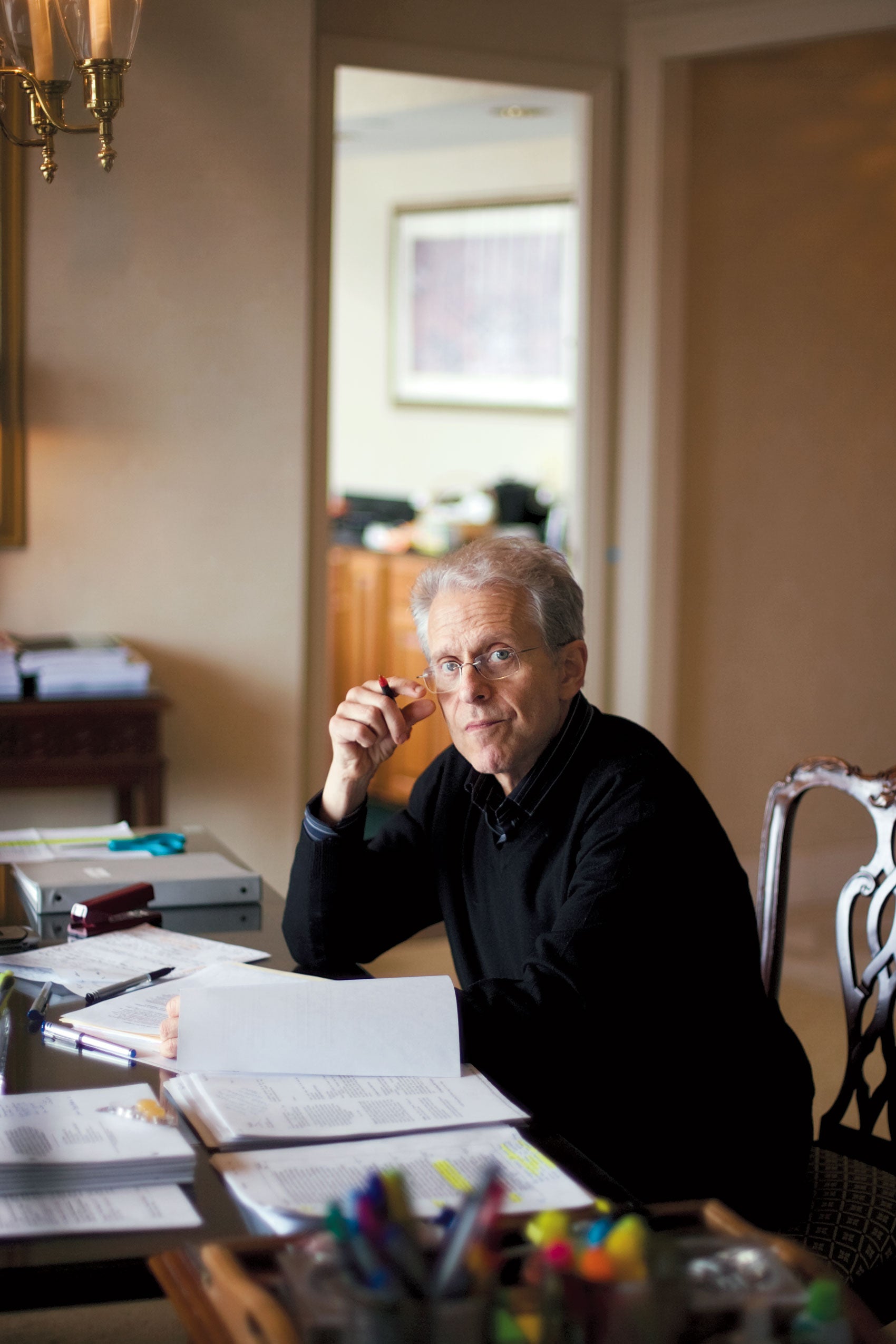

The following commentary by Professor Laurence Tribe ’66 appeared in the Washington Post on July 13 and July 14, 2009.

The Sotomayor Hearings, Day One

Every Supreme Court nominee in recent times has come before the Senate Judiciary Committee ably coached on how to sound knowledgeable and thoughtful while revealing as little as possible that might lose crucial Senate votes. There has been no surprise in the opening statements and will be none in the rounds of questioning about Sonia Sotomayor’s prior statements or about her rulings in controversial cases involving gun rights or affirmative action, all of which are still pending in the federal courts and thus arguably beyond appropriate comment on her part.

None of us, meanwhile, has a crystal ball about the issues likely to confront the country, and thus the court. It could well be, in an era of dizzying technological and cultural change, that today’s fault lines between “conservatives” and “liberals” will predict as little about tomorrow’s lines of division as was true of FDR’s appointees, all of whom seemed aligned on issues of congressional authority over the economy that split the nation in the 1930s but who ended up at opposite ends of the spectrum on the civil liberties issues that defined the debates of the 1950s and 1960s. So, too, we must doubt the predictive value of notions like “originalism,” concepts like “judicial activism,” and, indeed, the entire hodgepodge of labels and slogans invariably trotted out during these summer rituals.

Especially in a case like that of Sotomayor, whose extraordinary personal and professional biography and long record of mainstream judicial rulings have combined to make her overwhelming confirmation a virtual certainty, we are entitled to wonder what the point of this entire exercise might be.

The odds that any Senator’s vote will be changed by what happens this week are vanishingly thin. So the hearings are less likely to help the Senate discharge its mission of providing “advice and consent” than to sharpen the public’s understanding of the constitution’s meaning and of the Supreme Court’s role in construing and enforcing the nation’s laws. The hearings that led to the Senate’s rejection of Robert Bork and its confirmation of Anthony Kennedy over two decades ago taught the public valuable lessons about the constitution’s protections for personal privacy and other rights implicit in, but not expressed by, the document’s text. But most of those who listen this week will not have heard those hearings, which were held over two decades ago. Unless the absence of suspense about the outcome turns these newcomers off altogether, these hearings may serve as a much-needed introductory seminar in constitutional law. But even if the hearings merely enable the nation to focus more closely on who is actually raising meaningful questions and who is merely posturing, the process will have been worthwhile.

The Sotomayor Hearings, Day Two

Sadly, the Sotomayor hearings thus far have served to confirm my prediction that these rituals are structured to reveal as little as possible about the kind of justice a nominee will make. Sonia Sotomayor’s impressive academic record and extraordinary legal and judicial career already established her ample qualifications to serve. Her precise handling of the questions, to the degree they were substantive, has largely confirmed that conclusion.

Of greater interest to some has been the way Sotomayor would handle questions about the candor she displayed in speeches addressing the way a judge’s personal experience shapes the way that judge will rule in difficult cases. That candor, to me, is part of what commends her as a jurist. But it is also part of what the conventional wisdom tells a nominee to deny. And, sure enough, Sotomayor, in her exchanges with Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-Ala.), sought to deny it, offering several alternative readings of what she had repeatedly said and insisting that, in every case, she would strive to set her experience and perspective aside so that “the law” would command the result.

Attending to one’s prejudices and doing one’s best to set them aside is admirable. Convincing oneself that one can render judgments in a way that makes one’s personal experiences and views irrelevant is dangerous self-deception. Why, after all, do the justices so often disagree about what result “the law” commands? What accounts for their different perceptions of the rules of law that govern disputes and of the facts involved in those disputes? Justice Antonin Scalia, among others, has publicly said that his own background and upbringing necessarily influence how he decides cases. How could it be otherwise?

Even if judges and justices were computerized robots, the way they decide cases would have to be influenced by the “background” built into their software. But judges are not robots, and the reason we have nine justices rather than one is precisely that we hope the differences among them will permit a collectively wiser outcome to emerge — that we think nine minds, nine lives, will yield better results than one.

“The life of the law has been experience,” as Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes reminded us. And it is the experience of each judge’s life that inescapably plays a role in how that judge perceives both facts and law. It’s too bad that the political dynamic at work in these hearings propels the participants to pretend otherwise.