Known as the ‘father of environmental justice,’ Dr. Robert Bullard, a professor of urban planning and environmental policy and director of the Bullard Center for Environmental Justice at Texas Southern University, recently received the Horizon Award from Harvard Law School’s Environmental Law Society. The award, presented every year to an individual who has made extraordinary contributions to environmental law and policy, recognizes Bullard’s “outsized role” in the environmental justice movement.

Recognized by Apolitical as one of the 100 Most Influential People in Climate Policy, Bullard is the recipient of a number of awards, including the United Nations Environmental Program’s Champions of the Earth Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2021, President Biden appointed him to the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council.

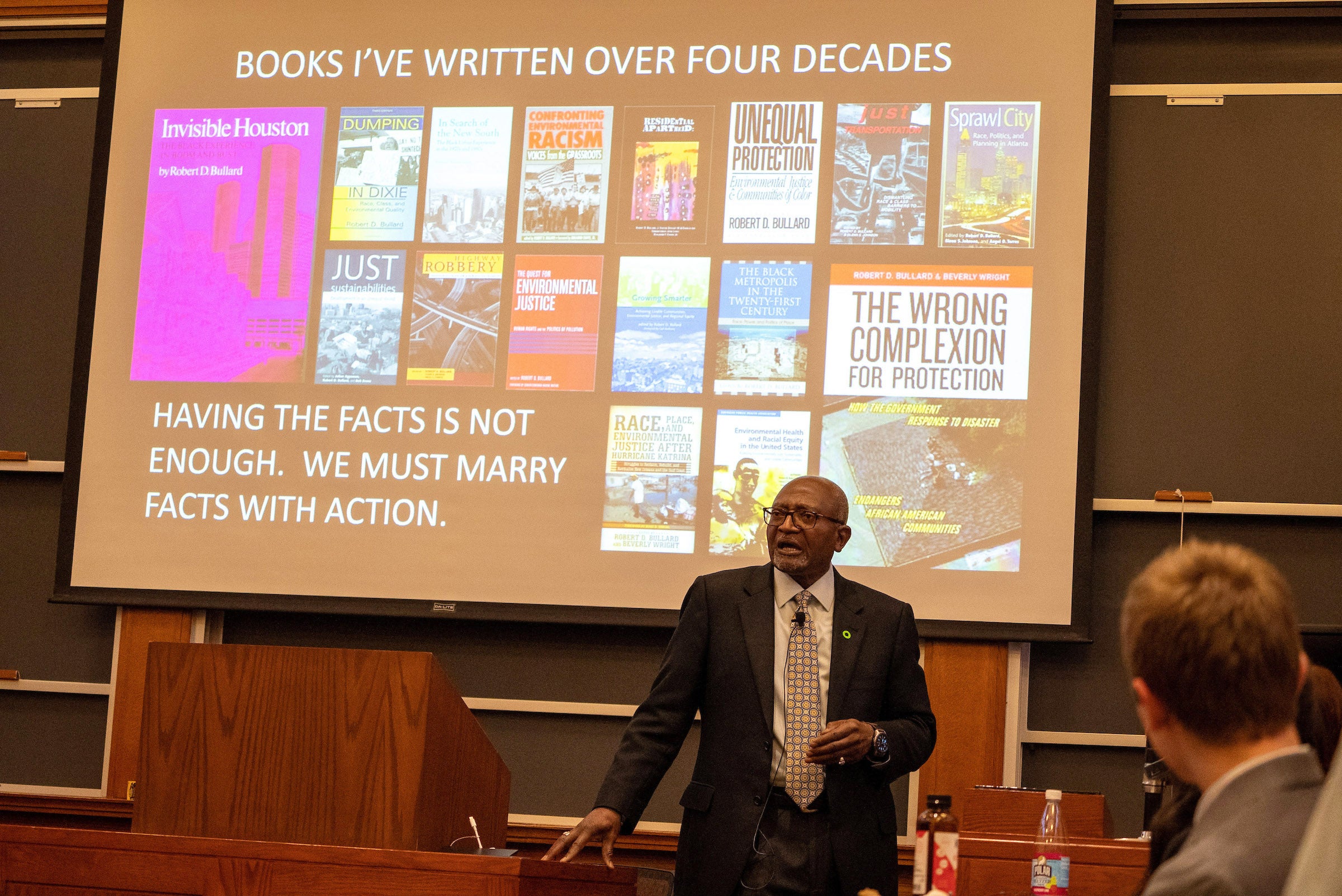

As part of the Horizon Award ceremony at Harvard Law School in April, Bullard delivered a talk about his more than 40 years of work in the environmental justice movement. We briefly spoke with Dr. Bullard about how he views the past, present, and future work of environmental justice.

Harvard Law Today: You’ve said, “In 1979 environmental justice was a footnote. Today it’s a headline.” How can we build on that awareness to create lasting change in communities disproportionately impacted by environmental pollution, disinvestment, and now climate change?

Robert Bullard: The headline means that it’s urgent and that it needs to be given the attention that it deserves. It’s above the fold as opposed to buried on page 29. I’ve been working on this for more than four decades, but a lot of our communities don’t have four decades to keep being under this burden of pollution and suffering when it comes to climate change. We maybe have a decade or two to deal with this.

We need more people to say, “I’m going to work on this issue. I’m going to stay with it for the long haul,” because we may not be able to solve it next year or the year after, but we have to stay with it as long as it takes to get the job done. That’s where we are right now. You have to be dedicated. You have to persevere. And sometimes you have to take defeat, get knocked down, but you have to get back up. You have to just resign yourself that this is going to be a struggle and that this is something that’s worth fighting for.

HLT: How can people who are fortunate enough to live in an area not currently impacted by environmental justice issues get involved?

Bullard: This question I get a lot. Most people in this country don’t live across the fence from a refinery. Most people don’t live in a community like East Palestine where the train derailment happened. But that doesn’t mean that you can’t empathize, or understand and support stronger regulations, stronger safety in terms of the railroad, in terms of enforcement, etc. Understand that the train wreck was only one part of the tragedy. Where are all those chemicals coming from? What communities live around those factories and plants?

Be aware that these communities are suffering right now, every day. Emissions that are coming out of energy facilities, whether it’s a refinery or chemical plant, benefit most of us who drive cars. And there are costs borne by those communities living around those refineries. You don’t think about that. Where do our trash and recycling go? It oftentimes goes where poor people — or people of color — live, and, not just garbage, but also waste coming from industrial production. When we talk about environmental justice, it means that you have to think beyond what’s happening to you personally. We need policies so that we don’t allow certain communities to become environmental sacrifice zones.

Areas of the south and Midwest are being impacted by stronger tornadoes and hurricanes because of climate change. You have to empathize. But we also have to talk about how to strengthen housing for people living in mobile homes. They’re not built to withstand this weather. And climate change is making storms more dangerous and frequent. Climate change is with us right now. We have to raise awareness and talk about how we’re going to create policies at the federal level.

HLT: How do you see the future of the environmental justice movement?

Bullard: Young people are mobilizing. They’re not going to wait 40 years to get something done. I’m optimistic and hopeful that young people can move quicker in addressing some of these issues as they come into their own. And their numbers are huge. They’re also bringing together climate, environment, health, and criminal justice issues. They’re mobilizing, voting, and changing elections. This to me is hopeful. And I’m optimistic. A lot of the good stuff that they’re doing doesn’t make the headlines because they’re doing it under the radar. I see the traction and I see them making change.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.