The following article by Jonathan Shaw appears in the January/February 2009 issue of Harvard Magazine.

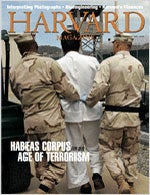

Huzaifa Parhat, a fruit peddler, has been imprisoned at Guantánamo Bay Detention Center for the last seven years. He is not a terrorist. He’s a mistake, a victim of the war against al Qaeda. An interrogator first told him that the military knew he was not a threat to the United States in 2002. Parhat hoped he would soon be free, reunited with his wife and son in China. Again, in 2003, his captors told him he was innocent. Parhat and 16 other Uighurs, a Muslim ethnic minority group, were living in a camp west of the Chinese border in Afghanistan when the U.S. bombing campaign against the Taliban destroyed the village where they were staying. They fled to Pakistan, but were picked up by bounty hunters to whom the U.S. government had offered $5,000 a head for al Qaeda fighters.

The Uighurs were officially cleared for release in 2004, but they remain at Guantánamo. They cannot be repatriated to China, because they might be tortured, and no other country will take them. The U.S. government does not want to allow them into the United States for fear of setting a precedent that might open the door for detainees it still considers dangerous. In 2006, after again being told that they were innocent, and becoming desperate, some of the Uighurs began mouthing off to their captors. They were sent for a time to Camp Six, a $30-million “supermax” prison for holding al Qaeda suspects in isolated cells.

In the tomb-like confines of this concrete prison, some of them began to crack up, says P. Sabin Willett ’79, J.D. ’83, a Boston-based attorney with Bingham McCutchen, the firm that has represented the Uighurs pro bono since 2005. [See profile in the 2006 Harvard Law Bulletin] “The Department of Defense has studied what happens to human beings when they are left alone in spaces like this for a long time and it is grim,” Willett notes. “The North Koreans did this to our airmen in the 1950s. The U.S. ambassador to the United Nations went to the floor of the General Assembly and denounced the practice as a step back to the jungle.”

When Willett visited Guantánamo in 2007, he met with Parhat, who was chained by the legs to the floor of his cell. Parhat had something important to tell him. Willett recounted the exchange in the Boston Globe. “About my wife,” the prisoner began.

“I want you to tell her that it is time for her…to move on…I will never leave Guantánamo.

…He looked up only once, when he said to me, urgently, “She must understand I am not abandoning her. That I love her. But she must move on with her life. She is getting older.”

Willett conveyed the message. She has remarried.

“Whatever you think about the human dimension of this,” says Willett, “the judicial dilemma of a federal court that has jurisdiction over a case—in which a person is held into his seventh year without lawful basis—and can give no remedy…that is an astonishing proposition. And it is a scary one.”

Parhat’s story is part of a much larger debate over how to fight an unconventional war against a largely invisible enemy who uses terrorism as a tactic. As cases like Parhat’s wend their way through the U.S. courts, the argument over how to balance individual freedoms against collective security pits civil libertarians passionate about human rights against seasoned national-security advisers equally committed to thwarting the next attack. In the fight against terrorists, the U.S. government has snatched suspects off streets abroad, interrogated them using techniques America’s allies still define as torture, and attempted to hold them without charge and without judicial review. The parley involves acts of Congress, presidential war powers, and judicial protections of constitutional rights. Sovereignty and jurisdiction, the separation of powers, the rule of law, the role of detention, due process, and standards of evidence—all are at issue, with tangible implications for foreign and domestic policy.

This is not the first time the government has limited civil liberties in times of national emergency. There are precedents from the Civil War and World War II. Then, as now, habeas corpus, a guarantor of perhaps the most basic right of liberty in the Anglo-American legal tradition, has emerged as a fulcrum in the debate over where to draw the line.

THE “GREAT WRIT”

Habeas corpus is an ancient remedy whose original purpose was to contest detention by the king. The origins of the writ, or “written order” (its Latin name means, loosely, “produce the body”), can be traced to thirteenth-century England. On June 15, 1215, at Runnymede, in a meadow beside the Thames west of London, the English barons who had banded together to impose legal restrictions on the power of King John forced him to affix his seal to the Magna Carta. One of its curbs on the sovereign’s power reads, in part, “No free man shall be seized or imprisoned…except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.” This was the “Great Writ”—the ancestor of habeas corpus. Although other common-law writs were in force throughout the British empire, only the writ of habeas corpus appears in the United States Constitution. Article 1, section 9, includes this single sentence: “The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.”

Habeas corpus requires a jailer to produce a prisoner in a court of law so the basis for detention can be reviewed. The Constitution presupposes this right, but its use has been sharply contested during previous wars.

In the post-9/11 era, does it even apply to Parhat and the other alleged terrorists held at Guantánamo? Does the writ run with U.S. territory, with citizenship, or with governmental power—wherever it reaches? Does it apply to prisoners of war? Are the detainees at Guantánamo POWs? How should they be treated? The answers affect the way Americans are perceived throughout the world—and the way Americans see themselves.

The Supreme Court has called habeas corpus “the fundamental instrument for safeguarding individual freedom against arbitrary and lawless state action.” English history prior to the drafting of the Constitution affords some insight into the Framers’ understanding of the Great Writ; its use thereafter constitutes the American legal precedents. In a 2008 analysis of British and American “habeas” jurisprudence in the Colonial era, G. Edward White, J.D. ’70, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law, and his colleague, Paul Halliday, conclude that judges were less concerned about whether a petitioner was physically in the country or abroad than whether he was held by “someone empowered to act in the name of the king.” The focus, in other words, was “more on the jailer, and less on the prisoner,” they write, more on the “authority of the sovereign’s officials” than on the “territory in which a prisoner was being held or the nationality status of the prisoner.” Even “alien enemies,” the subjects of a sovereign at war with Britain’s monarch, if “they were residents of, or came into, the king’s dominions” were allowed habeas review.

Their historical analysis concludes that “the jurisprudence of habeas corpus in England, its empire, and in America, is antithetical to the proposition that access to the courts to test the validity of confinement can be summarily determined by the authorities confining a prisoner. At a minimum,” they write—extending the implications of their findings to the present day—“the history…suggests that there should be some opportunity for a judicial inquiry into the circumstances by which a Guantánamo Bay detainee was designated…eligible for indefinite confinement.”

But in times of crisis, habeas review by the courts can be suspended. There have been only four such suspensions in U.S. history, says Story professor of law Daniel Meltzer: one in the Civil War; one during Reconstruction; one in the Philippines after the Spanish-American War; and one in Hawaii during World War II, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Of these, the suspension of habeas corpus by President Abraham Lincoln is perhaps the most interesting because he claimed authority that the Constitution appears to grant Congress.

The circumstances under which Lincoln acted on April 27, 1861, were dire. Virginia had just seceded, and Maryland’s legislature seemed on the verge of following, threatening to cut Washington off from the North. Union reinforcements from Massachusetts who had been sent to protect the capital city were attacked by an angry mob as they passed through Baltimore. It was as clear a case of rebellion as one could imagine. Lincoln authorized one of his generals to suspend habeas corpus in the military district between Washington and Philadelphia.

To preserve the Union, the president probably broke the law. The “suspension clause,” as the constitutional language regarding habeas corpus is sometimes called, appears in the part of the Constitution dealing with legislative, not executive, powers. It is phrased as a limit on suspension, Meltzer says, probably because in England, Parliament had a history of passing “acts which took away the power to provide the writ.” In the United States, therefore, the Founders, “concerned about the threat to liberty that those practices posed…incorporated limits on the power to suspend the writ.” In Meltzer’s view, the evidence from English history, from the drafting of the Constitution, and from its final phrasing all suggest that only the legislature could suspend. “The core of the writ is to try to protect against executive detentions. As a matter of common sense,” he points out, “the idea that the executive could be the one to suspend the writ that is designed to protect against executive overreaching—that’s a little bit like foxes and chicken coops.”

Lincoln famously defended his actions before Congress, arguing that he had acted out of necessity. “[A]re all the laws, but one, to go unexecuted and the Government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated?…would not the official oath be broken if the Government should be overthrown, when it was believed that disregarding the single law would tend to preserve it?” Lincoln went on to say that “as the provision was plainly made for a dangerous emergency, it cannot be believed the framers of the instrument intended that in every case the danger should run its course until Congress could be called together, the very assembling of which might be prevented, as was intended in this case, by the rebellion.” Crucially, Lincoln said of his actions that he trusted, “then as now, that Congress would readily ratify them.”

As Daniel Farber of Berkeley’s Boalt Hall School of Law writes in Lincoln’s Constitution, “Lincoln was not arguing for legal power to take emergency actions contrary to statutory or constitutional mandates.” Nor did he claim legal immunity. “Instead,” writes Farber, “his argument fit well within the classic liberal view of emergency power. While unlawful, his actions could be ratified by Congress if it chose to do so.” And that is what happened.

THE “WAR ON TERROR”

The parallels to today center on the government’s use of emergency executive power to detain prisoners captured in the armed conflict with al Qaeda. Because there was no rebellion or military invasion, neither President George W. Bush nor Congress invoked a constitutional right to suspend habeas corpus. Instead, the government sought to prevent habeas review by jailing prisoners beyond the jurisdiction of American courts.

“In the weeks after 9/11,” recalls John Yoo ’89, who was a deputy assistant attorney general, “lawyers at State, Defense, the White House, and the Justice Department formed an inter-agency task force to study the issues related to detention and trial of members of al Qaeda. The one thing we all agreed on was that any detention facility should be located outside the United States. We researched whether the courts would have jurisdiction over the facility. Standard civilian criminal courts might not even be able to handle the numbers of captured terrorists, overwhelming an already heavily burdened system. Furthermore, if federal courts took jurisdiction over POW camps, they might start to run them by their own lights, subordinating military needs and standards, and imposing the peacetime standards with which they were most familiar. We were also strongly concerned about creating a target for another terrorist operation.”

In this view, no location was perfect, says Yoo, now a law professor at Berkeley, “but the U.S. naval station at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, seemed to fit the bill … Gitmo was well-defended, militarily secure, and far from any civilians.”

Former presidents’ use of the base provided some guidance on whether the U.S. courts would have jurisdiction: “The first Bush and Clinton administrations had used Gitmo to hold Haitian refugees who sought to enter the United States illegally,” Yoo says. “One case from that period had held that by landing at Gitmo, Haitians did not obtain federal rights that might preclude their [forcible] return. This suggested that the federal courts probably wouldn’t consider Gitmo as falling within their habeas jurisdiction, which had in any event always, in the past, been understood to run only within the territorial United States.” Keeping the prisoners at Guantánamo thus seemed to preclude the possibility that they could seek habeas corpus review of their detention. As White and Halliday’s 2008 analysis suggests, this view would prove controversial.

The fact that the United States is legally engaged in a continuing armed conflict for which the president was specifically granted war powers also had important ramifications for the prisoners. On September 14, 2001, Congress authorized the president to use all necessary and appropriate force against the persons, organizations, and states responsible for 9/11. During a war, prisoners are held not according to guilt or innocence, as in criminal cases, but as a practical matter: if released, they would likely resume the fight, so governments have traditionally detained enemy soldiers without charge until the hostilities end. (During World War II, notes Shattuck professor of law Jack Goldsmith, when “the United States held over 400,000 POWs in this country with no access to lawyers and no due-process rights,” the power to detain was so uncontroversial that almost no one went to court. When one POW, an American citizen, filed a petition for habeas review, a lower court held that the president was allowed during war to detain even an American citizen—without charging him with a crime or affording him a trial—because the man had been working for the enemy. “There was no doubt that he could go to court,” says Goldsmith, “but it turned out that he had no rights. The court dismissed the habeas corpus petition.”)

Goldsmith, who served as a U.S. assistant attorney general from 2003 to 2004, believes that authorizing a war against al Qaeda was the right thing to do because “military power has proven essential in hunting down” al Qaeda terrorists abroad. But with respect to “this non-criminal military detention power that we have used in every prior war,” says Goldsmith, there are at least “two huge differences” that “make people skeptical.”

“One is that this enemy does not distinguish itself from civilians,” he says. During World War II, almost every enemy soldier was “caught in uniform wearing ID tags. There weren’t any mistakes, and no one claimed that they were mistakenly detained that I know of,” Goldsmith says. “But a lot of people think that these guys in Gitmo are innocent, because they were caught out of uniform. There is a big question about how you tell who is the enemy.” (Adds Meltzer, “We may need a more robust inquiry into the factual basis for detention when we are dealing with a situation in which the risk of error is considerably higher than in conventional wars.”)

Compounding the problem, Goldsmith says, is that this war “has an indefinite duration. You might want to take the risk of mistakenly detaining someone for five years [the length of World War II] because you are always going to make mistakes. But there is a big difference if you think there is a higher likelihood of someone being innocent and being put away for the rest of their lives.”

These factors, combined with radical changes in international notions of justice and human rights, Goldsmith says, make this “legitimate power to detain a member of the enemy” suddenly seem “illegitimate in this war.”

Political support for expansive presidential emergency powers is also far less than it was during the Civil War or World War II, when presidents overstepped their constitutional authority but were forgiven. Partly, this is because after 9/11 the executive branch preferred to act unilaterally, often on the basis of legal opinions it kept secret. Rather than consulting with other branches of government, requesting forbearance, or attempting to sway public opinion as Lincoln did, the Bush administration frequently, as Goldsmith puts it, “substituted legal analysis for political judgment.”

At a February 2008 symposium called “Drawing the Line,” Goldsmith (whose book The Terror Presidency provides an insider’s view of Bush administration policies) and journalist Ron Suskind (whose book The One Percent Doctrine is deeply critical of those policies) painted similar pictures of what life has been like for high-ranking government insiders since 9/11. Every day, the president and other officials are handed a “threat matrix,” often many dozens of pages long, listing the threats directed at the United States within the previous 24 hours. “On 9/11,” says Goldsmith, “the president’s and the public’s perception of the threat was basically the same.” But over time, the public’s perception of the threat has waned, whereas what the president sees “would scare you to pieces.”

Political leaders have made no serious effort to bridge the gap between these perspectives. And in the absence of winning words, government actions have eroded public support. The treatment of the Guantánamo prisoners—denying the Geneva Convention protections legally extended to POWs on the one hand, while justifying indefinite detention on the basis of war powers on the other—whether legal or not, has led to charges of hypocrisy. The United States has argued that because al Qaeda fighters do not wear uniforms and do not obey the laws of war, they are not entitled to the protections normally accorded to POWs. That may be true, allows Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Anthony Lewis ’48, NF ’57 (who has written books on constitutional issues and formerly wrote about them as an op-ed columnist for the New York Times), “but to extend this denial of POW status to the Taliban, which governed Afghanistan and with whom we are fighting a conventional war, as Bush has done, is complete nonsense.”

THE COURT AND THE CONSTITUTION

Soon after congress authorized the use of force, U.S. courts began reviewing the legitimacy of military detentions, hearing habeas corpus petitions filed on behalf of prisoners held as “enemy combatants” who claimed that they were not members of al Qaeda or any other terrorist group. Among these was the case of Yaser Hamdi, an American citizen captured in Afghanistan in 2001 and turned over to U.S. military authorities there. Although initially detained at Guantánamo, he was moved to a military holding cell in Virginia when his U.S. citizenship was discovered. The government asserted its right to hold Hamdi as an unlawful combatant without right to an attorney and without judicial review.

“In retrospect,” says Goldsmith, “it would have been a lot better if the government had taken the opposite posture. The first argument that they made about habeas corpus was that Hamdi—a U.S. citizen held in the United States—basically didn’t have habeas corpus rights. Right out of the box, they wanted to get rid of all judicial review, even in the United States.”

When Hamdi’s father, Esam, filed a habeas petition on his son’s behalf, stating that Yaser was in Afghanistan as a relief worker, not fighting for the Taliban as the government alleged, a federal circuit court of appeals found that because he was captured in an active war zone, the president could detain him without a court hearing. But in June 2004, the Supreme Court held that the executive branch of government does not have the power to indefinitely detain a U.S. citizen without judicial review. Eight of the nine justices agreed that Hamdi not only had the right to be heard in court, he had additional due process rights as an American citizen under the Constitution. Justice Antonin Scalia, LL.B. ’60, posed the strongest constitutional argument for limiting the executive power of detention under these circumstances. There were just two options, Scalia wrote: either suspend habeas corpus, as the Constitution allowed in the case of invasion or rebellion, or try Hamdi for treason, as described in Article 3, the Constitution’s section on judicial power.

Hamdi, who was released without a criminal trial on the condition that he renounce his U.S. citizenship, now lives in Saudi Arabia, where his parents moved when he was young.

In another ruling announced the same day, Rasul v. Bush, the Court found that U.S. control of the naval base at Guantánamo, leased from Cuba on a permanently renewable basis, was sufficiently complete that the base was effectively U.S. territory. This territorial interpretation extended the jurisdiction of the federal courts to Guantánamo, giving the foreign nationals held there a right under federal law (though not necessarily a constitutional right) to file habeas corpus petitions in U.S. courts.

But the Court did not say what sort of substantive rights the foreign prisoners would have once they got to court—what sort of evidence would be admissible, for example—instead suggesting that this was the sort of policy Congress could legislate.

THE JUDICIAL DILEMMA: DEFERENCE OR CONSCIENCE

Besides allowing review of the basis for detention, habeas corpus also gives courts the opportunity to assess the lawfulness of a prisoner’s treatment while being held. Such was the case in Padilla v. Rumsfeld, decided the same day as Hamdi and Rasul. José Padilla, an American citizen, was picked up at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport in 2002 on his return from Pakistan and accused of planning to detonate a radiological “dirty bomb” in an American city. President Bush ordered him held as an enemy combatant. Though the Supreme Court declined (on a technicality) to rule on the validity of Padilla’s military detention, the case became significant anyway. During arguments, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, L ’59, asked what would happen if, in the course of a military detention not subject to judicial review, the executive, not a mere soldier, decided that mild torture would be useful to extract information. Paul Clement, representing the government, responded, “Well our executive doesn’t, and I think, I mean….” Ginsburg pressed on: “What’s constraining? That’s the point. Is it just up to the goodwill of the executive, or is there any judicial check?”

Two days later, the revelations of abuse at Abu Ghraib became public. Eventually, it became clear that the government had condoned the use of coercive interrogation techniques—some of them considered torture under international law—against suspected terrorists, whether they were U.S. citizens or not. The aim was to garner “actionable intelligence” that might prevent another attack, and to force confessions that might be used in a military tribunal (even if they would be inadmissible in ordinary court). Jenny S. Martinez, J.D. ’97, an associate professor of law at Stanford University who is one of Padilla’s lawyers, says that he was among those subjected to years of isolation and mistreatment, and that he suffered serious harm as a consequence.

Historically, there has been a tradition of judicial deference to the executive branch during periods of crisis, says Watson professor of law Adrian Vermeule. In the Padilla case, the later decision of a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit—that war powers gave the president the right to hold Padilla indefinitely—fit that pattern. But courts eventually begin to reassert their authority as crises pass, says Vermeule. The government, perhaps fearing that it might lose both the case and the precedent of a favorable ruling on a second appeal to the Supreme Court, dropped the charges against Padilla and indicted him in a civilian court on a completely different set of charges than those it had used to justify his 42-month military detention. This “game of bait and switch,” says Martinez, undermines the rule of law by allowing the government to avoid judicial review. (Padilla is now appealing in civilian court a conviction of conspiracy to commit jihad in Bosnia and Kosovo. No mention was made during his trial of a dirty-bomb plot against the United States.)

CONGRESSIONAL INTERVENTION

The series of Supreme Court rulings against the government in 2004 sent the message that if the president’s war policies were to continue, they would need statutory backing from new congressional legislation. Armstrong professor of international, foreign, and comparative law Gerald L. Neuman says that even though holding or prosecuting terrorists may involve special difficulties that argue for judicial deference to executive actions, that “doesn’t mean the executive should be trusted to unilaterally resolve all the questions” surrounding terrorist detentions and trials. “Due process is a flexible concept,” he says, “that allows courts to account for individual and government interests alike in order to give people an opportunity to demonstrate their innocence without endangering national security. Executives should be getting Congress’s help,” he adds, “and courts need to be trusted to some degree.”

Congress attempted to legitimize the administration’s detention policies with the Detainee Treatment Act (DTA) of 2005, which condoned the use of military commissions to try subjects. But in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, the Supreme Court found in a 5-3 decision that the commissions were unlawful because they did not follow the military’s own previously established rules. At a minimum, the Court said, the prisoners deserve rights under Common Article 3 of the Geneva Convention. (Habeas corpus is the mechanism through which these rights can be invoked.)

Congress responded by passing the Military Commissions Act (MCA) of 2006, whose purpose was to put military-commission trials on a legal footing. But in addition to allowing use of hearsay evidence and other evidence not permissible in civilian trials, the MCA stripped Guantánamo prisoners of their statutory right to habeas review. The question remained, however, whether a constitutional right to habeas corpus extended to Guantánamo. In a landmark June 2008 case, Boumediene v. Bush, decided by a 5-4 margin, the Supreme Court found, as it had in Rasul v. Bush, that Guantánamo was effectively a territory of the United States. Even though the prisoners were not citizens, they had a constitutional right to habeas review.

Proponents of broad executive powers, including John Yoo, characterized decisions such as Hamdan and Boumediene as overreaching by the Court. Goldsmith says the Boumediene decision was “extraordinary in the sense that it was the first time in American history that a court had invalidated a wartime measure that Congress and the president agreed on during war.”

In order to reach that opinion, the Supreme Court had to find that the constitutional right to habeas corpus extends to Guantánamo, and that the substance of the habeas review protected by the Constitution was not being provided by some other means. Chief Justice John Roberts ’76, J.D. ’79, argued in his dissent that Congress had created a habeas-like system in the DTA, which allowed District of Columbia circuit courts to review the decisions of military tribunals. Agreeing with Roberts, Goldsmith says, “There is an important principle here that the Court should not unnecessarily reach out to strike down an act of Congress if there’s a way of upholding it.” But Neuman, who filed an amicus brief in the Boumediene case, says that to do that, the Supreme Court would have had to interpret the intent of the DTA as being the establishment of an adequate and effective habeas substitute, amounting to a “legal fiction that the statute meant something it couldn’t possibly mean.”

DETENTION AND DEMOCRACY: A MIDDLE PATH

In the meantime, “We still don’t have a system for dealing with these detainees,” Goldsmith points out. Current and former government officials, conservative and liberal alike, have suggested that the president-elect will need to work with Congress to create a legitimate detention policy to replace the system in place now: habeas review of military detentions. Any new policy would need to establish the legal basis for detention, because habeas corpus is a remedy that empowers a judge to release a person who has been wrongfully held, a determination that hinges on the legal basis of the imprisonment.

What the United States is now doing with its Guantánamo prisoners, explains Ames professor of law Philip B. Heymann, constitutes a form of preventive detention. In criminal law, preventive detention provides the rationale for holding dangerous criminals pending trial, illegal immigrants pending deportation, sexual predators, and the criminally insane who are dangerous to themselves or others—akin to the wartime right to hold POWs to keep them from returning to the battlefield. But after 9/11, Heymann says, “[W]e invented a new category of detention [i.e., of unlawful enemy combatants] that didn’t have the protections built into peacetime detentions, such as periodic review by a judge, and that didn’t have the protections built into POW rights under the Third Geneva Convention.”

Not since the United States fought the Barbary pirates in the early 1800s has the country faced an analogous situation, he points out: waging a war, but not a civil war, and not against a state. “Most of the remaining Guantánamo detainees are being held on the basis of a law-of-war variation of alleged membership in a group—al Qaeda or its affiliates—that has been deemed dangerous”—historically, he says, one of the weakest justifications for holding someone. “A very high percentage of non-dangerous individuals were detained under this theory,” which is why the courts have demanded extensive habeas reviews of military detentions.

“Lawyers have not been inventive in dealing with the problem we face,” Heymann continues. “They’ve lined up largely as defenders of presidential power to protect us in a time of danger, or as defenders of the traditional Constitution and statutes. What we needed was a creative response.”

In 2004, Heymann met with then Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, J.D. ’82, and White House counsel Harriet Miers to try to persuade them that a novel detention policy should not be established by executive fiat—that instead there is a “democratic way, preserving the traditional separation of powers to arrive at a reasonable accommodation. Their reaction,” he says, “was, ‘We can do anything we want now. Why would we want to do that?’”

In the realm of possible remedies are three leading alternatives, each with its advocates. One is to use the existing criminal-justice system, with some modifications—including a delay of trial, pending a search for usable, unclassified evidence. A second would be to designate detainees as POWs with full Geneva Convention protections, but also to impose congressionally renewable time limits on detention, so that prisoners are not incarcerated forever. And a third would create a new national security court with special procedures and its own standards of evidence for handling terror suspects. “We desperately need Congress to step up to the plate to design a program that will tell us who the enemy is, precisely, and what protections they get, and what this system should look like for legitimating these detentions,” Goldsmith says.

Heymann advocates use of the criminal law to handle terrorists. “Guantánamo is a big political problem, but only a small-scale detention problem” going forward, he says. Putting aside the 250 people who are there now, only about 10 new prisoners are sent to Guantánamo each year, he says; with such small numbers, the government could easily subject anybody it thought was a dangerous terrorist planning to attack the country to trial. “I think we can just skip Guantánamo completely, take him to any federal trial court, and either convict him or release him,” Heymann says.

This criminal approach faces one major hitch, he notes. In some of these cases, the government will pick up someone for whom the basis of detention cannot be revealed “without breaking a promise to a foreign country or endangering sources of evidence, whether it be the name of a spy or a classified electronic surveillance method.” For that type of case, Heymann advocates creating a new subcategory of detention pending trial. “I think we would have to delay the trial while we seek evidence that can be used against him. And if we can’t find usable evidence after some reasonable period of time, like three years, we’re going to have to deport him and release him.”

But if a criminal approach required detention for three years in some cases, as Heymann advocates, legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin ’53, LL.B. ’57, thinks it would be better “to designate those we want to hold for such a long period as POWs. That would make plain that they are entitled to the protections of the Geneva Convention, which are substantial … The difficulty is that POWs can be held until the end of ‘hostilities,’ and it is unclear what that means in the case of alleged terrorists,” says Dworkin, who has been a professor at Yale, Oxford, and University College London and is now a professor of philosophy and of law at New York University. “So I would prefer new legislation to specify a [time] limit, subject to renewal by fresh legislation, and to establish procedures for habeas review of the designation in accordance with Boumediene.”

Heymann forcefully rejects the third alternative—creating a national security court or other novel statutory system for civil detention of terrorists. “The problem with these schemes, even when created by legislation and administered by the judiciary, is the vagueness of the standard for detention,” he asserts. The United States runs the risk of “creating the type of regime…that has proved a dangerous failure in other Western countries” and that, in the international arena “would constitute an unparalleled assertion of executive power to seize and detain people living in other countries, compared to asserting a right to try the individual for violation of our criminal statutes,” he writes. “The gains from this regime would have to be very great to warrant the departure from hundreds of years of Western traditions in this way. They simply are not. If we can extradite and try more than a dozen powerful paramilitary Colómbian warlords for drug trafficking charges, we can and should do the same with supporters of al Qaeda and its affiliates.”

THE PITFALLS OF PREVENTIVE DETENTION

David H. Remes, J.D. ’79, an attorney representing 17 Guantánamo prisoners, warns that “This idea of setting up a new system and doing it ‘right’ has a deceptive appeal, because it appears to offer a sensible middle ground between the abuses and outrages committed by the Bush administration and the soft-headed idealism of civil libertarians. Everybody loves the approach that rejects ‘the extremes of the left and the right.’ But the world isn’t divided into one extreme versus another extreme. It’s divided into right and wrong.” Remes scoffs at the idea of “preventive detention” as a justification for holding his clients. “Are we talking about some form of pre-crime?” he asks. “That is what some very decent and thoughtful academics and others are proposing. The idea was last proposed by Attorney General John Mitchell in the Nixon administration,” he says, “to deal with supposed threats to domestic security from within. It was roundly rejected as contrary to our most basic values.”

Remes, who gave up a partnership at Covington & Burling LLP to found Appeal for Justice, a nonprofit human-rights litigation firm, represents (with his former firm) 15 Yemenis at Guantánamo. He also represents, together with Reprieve, a British human-rights organization, two other detainees: an Algerian fighting repatriation because he fears torture or death, and a 61-year-old Pakistani businessman who was abducted in Thailand. He sharply criticizes the way the government captured these men, the way they have been treated subsequently, and the evidence on which they continue to be held. He began filing habeas review petitions on behalf of his clients in July 2004, after the Rasul decision. All along, the government has maintained that his clients are enemy combatants, he says, but has been “fighting tooth and nail against ever having to prove its allegations in a court of law. All the public knows,” he says, “are the allegations, because the government has kept all of its evidence secret.”

“It’s absolutely critical to determine reliably whether you have apprehended a civilian or a warrior,” he continues. “That determination has to be made fairly. You can’t simply sweep someone up and define him as a warrior, which is what the Bush administration did.” Even after Rasul, he says, the government cherry-picked the evidence that its Combatant Status Review Tribunals could review to justify detention—“which made it a rather one-sided affair, even overlooking all the other flaws.” After the Boumediene decision, the government threw all the CSRT evidence away, says Remes, and filed a new set of accusations, with a new pile of evidence to support them. “They added allegations, they dropped allegations, they scuttled some evidence, and they added other evidence,” he says. “It’s really a travesty.”

And yet, Remes says, it is the same type of evidence. Lawyers like Remes, who represent the detainees, are the only ones outside of government who have seen the evidence firsthand. Remes can’t discuss it directly: it is all classified, held in a secure facility. But he says that virtually everything that the government relies on to call these men enemy combatants consists of statements by the prisoners themselves or statements about the prisoners by other prisoners. Many of these statements were elicited using torture, he says, or by “promising prisoners early release or a pack of cigarettes or a better cell.” Remes mentions Muhammad al-Qahtani, whose interrogation logs were published in Time magazine, and who was made to bark like a dog, wear women’s underwear on his head, suffer extremes of hot and cold, and go for long periods without sleep. “The government showed him a picture book and said, ‘Okay, tell us—who are the terrorists at Guantánamo?’ And al-Qahtani simply said, ‘Him, him, him, him, and him.’ And other prisoners did the same thing.”

Remes says that, while going through the government’s evidence, he has found instances where several prisoners, shown the photograph of another prisoner, each identify the man in the picture as al Qaeda, but give him different names. The government concludes that they all know the man, but by different aliases, rather than concluding that none of them actually knows the man. Remes also maintains that the use of torture, which is known to produce false confessions from people who have no information, makes anything they say unreliable. “That means that if they are terrorists, they are rendered practically unconvictable,” he says, “and if they are not, they have suffered a gross injustice.”

Forty percent of the detainees who remain at Guantánamo are Yemenis, he notes, because the United States has been unable to work out an agreement with Yemen for their return; by contrast, 90 percent of the Saudis and all of the Europeans have been returned, even though the U.S. government viewed most of these men as enemy combatants. “My point being,” Remes says, “that whether or not you are an enemy combatant seems to have nothing to do with whether or not you get released.” Two of his clients were cleared for release in February 2006. They are still at Guantánamo. Other men who have not been cleared for release have been sent home.

The reality at Guantánamo, he says, is that—so far—release has hinged on diplomacy, not justice. “People always ask me, ‘Are your clients guilty or innocent?’ And I ask them, ‘Guilty of what?’ And people really can’t articulate what it means to be guilty. They may say, “Well, guilty of terrorism.’ And I ask, ‘Well what do you mean?’ And there is a pause. And then they say, ‘Well, attacking the United States.’ But few if any of these men have attacked the United States. The ones who allegedly did are on trial before the military commissions or they are dead.

“Certainly if you were involved in the World Trade Center attach or the bombing of the USS Cole or U.S. embassies or you threw a grenade at an American soldier or shot at an American convoy, you have attacked the United States,” Remes continues. “No question that you should be brought to justice. But taking the Taliban’s side in the civil war against the Northern Alliance, or doing relief work, or spreading the word of Islam in Afghanistan—how do these make you an enemy of the United States? “The government has been so successful since 9/11 in portraying these men as the worst of the worst, as vicious killers, that people simply take that as a given. Most of the these men were fish caught in a net when the U.S. started bombing Afghanistan and the Northern Alliance started advancing.”

At that point, Remes explains, “the U.S. was offering $5,000 bounties to any Afghan that could turn over terrorists. So you had a lot of Afghani bounty hunters picking up Arabs and selling them to the United States, simply asserting that the men were Taliban or al Qaeda. Similarly, many men were picked up by Pakistani border guards when they came through the mountains and sold to the United States.” Five thousand dollars, he notes, is a huge sum in Afghanistan: “The U.S. propaganda was, ‘You’ll be set for life.’” Almost all of the men held at Guantánamo were seized in this way, he says; only about 5 percent were captured by U.S. forces.

Remes believes that “a lot of what is going on at Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib, and in the court system here, is less about whether these individuals are terrorists than it is about whether the executive branch can do whatever it wants, free from any accountability to the other branches of government. I don’t buy the thesis that the administration’s big mistake was not going to Congress to authorize what it was doing. Whether an activity has political legitimacy or not is beside the point. It’s what’s being legitimized that counts.”

The story of what happened to one man at Guantánamo—Parhat, the Uighur who released his wife from having to share in his captivity—may come to a resolution soon. A federal appeals court is expected to rule in January on the possibility of releasing him and the 16 other Uighurs into the United States. But the issues underlying Parhat’s story—how a democratic society preserves its values and protects its citizens when faced with an unconventional threat—will not go away, and the president-elect and his eventual successors will likely be grappling with them for years to come.