The best advice retired United States Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer ’64 ever received had nothing to do with the law.

It came from David Bazelon, who was serving as the senior judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in 1980 when Breyer was first appointed to bench. The older, more experienced jurist told his new colleague that he should prepare for the possibility that he’d be donning a judge’s black robe for years to come.

“This takes a long time, being a judge,” he recalled Bazelon saying. “You’re going to be here a long time. And … the main thing I can tell you is: Get an interest, get a hobby, and let it have as little to do with law as possible. And so, what I did — which is a little nutty, I agree — but I spent quite a lot of time learning French.”

Fifty years later, Breyer, now the Byrne Professor of Administrative Law and Process at Harvard Law School, shared the same advice with Harvard lawyers in training: Get a hobby and study a foreign language.

Breyer’s extracurricular avocations seem not to have inhibited his judicial career. After serving 14 years as an appeals court judge, he was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1994. Following his retirement in 2022, he returned to the Harvard Law School faculty, where he had taught from 1967 to 1980.

And Breyer’s Francophilia, he noted during an event at Harvard Law, has recently paid off once again, with the publication of the French language version of his most recent book, “Reading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, not Textualism.”

“And moreover, it’s a better title in French,” he declared to a room filled with students, faculty, and staff. “‘Interpréter la Constitution américaine: La lettre ou l’esprit’…”

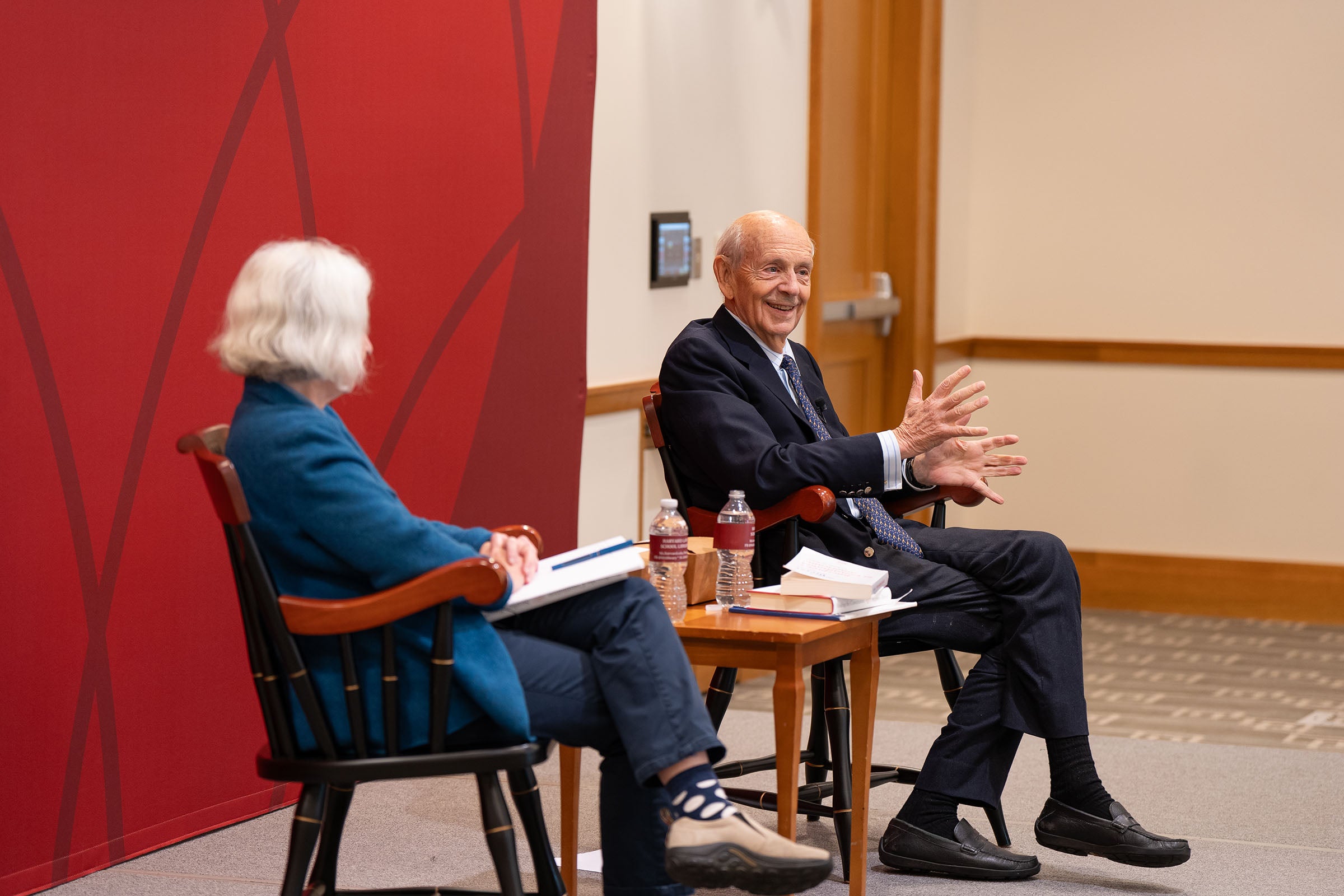

Over the course of nearly an hour, Breyer shared his perspectives on the role of appellate courts, the importance of state law, and his time as a Supreme Court justice with his interlocutor for the afternoon, Martha Minow, the 300th Anniversary University Professor and former law school dean, and with an in person and online audience.

So, Minow asked, what do appeals court judges actually do? In response, Breyer recounted a story he often shares when speaking to seventh-grade school children, whose attention, he averred, is sometimes hard to keep.

“I was in France, and I read in the newspaper a story of a biology teacher in high school who was traveling from Nantes to Paris, and in the basket down here he had 20 live snails,” he said. “So, the conductor comes up, and she’s looking at the basket, and she opens it up and says, “Escargot. … You have a ticket for the snails?”

The fare book, she noted, says that animals travel for the cost of a half-price ticket. The biology teacher was aghast — surely, he responded, that rule applies only to larger animals like dogs, cats, or perhaps rabbits. But the conductor wasn’t having it. After all, aren’t snails also animals?

For Breyer, this lighthearted example encapsulates the type of interpretation that appellate courts and judges are asked to make. “That’s what judges do,” he explained. While in this case, the question centered on whether snails count as animals for the purposes of the railroad’s rules, appellate courts often deal with weightier words and concepts, such as “freedom of speech” or “the right to bear arms.”

“But it’s the same idea,” he said. “That’s what appellate judges do. What is the scope of those words? Do they apply in this situation?”

Despite serving on federal courts for more than four decades, Breyer seemed to play down the importance of their role in American life. Speaking to the students in the audience, he asked why they spend their first year in law school mostly learning about various aspects of state law, such as contracts and property.

“Because that’s where the law is made,” he said, answering his own query. Americans who want to influence the laws that most affect themselves and their families should skip a trip to Washington, D.C., and instead move to state capitals like Sacramento, advised Breyer, who lived and worked inside the Beltway for the better part of half a century, beginning in 1973, when he served as an assistant special prosecutor on the Watergate case.

Even the Supreme Court, he noted, has limited influence. After all, it takes only a fraction of the 7,000 to 8,000 cases they are asked to review. [During Breyer’s time as a justice, the number of cases decided by the Court varied from a low of 51 in the 2009 calendar year to 116 in 2008.]

“Are they always the most important cases?” Breyer asked. “No. Sometimes yes. But they’re all over the place.” How are they selected? “Almost always, the criterion is, did the lower courts come to different conclusions on the same question of federal law,” he explained, adding that so-called circuit splits aren’t the only reason justices might intervene. And despite the many news headlines about hotly contested rulings pitting conservative versus more liberal justices, Breyer noted that approximately 40 to 50% of the Court’s decisions in any given year during his service were unanimous.

Minow followed up with a question about the role of oral arguments. “How much of the questions are really trying to argue to your colleagues?

Breyer said that while different justices may approach the process differently, “For me, the best kind of question, which comes up occasionally, [is one to which] I don’t already know the answer.” In those instances, he said he deliberately formulated his query “in a way that will get the lawyer away from what he’s supposed to be doing, which is defending the client, and I can get a truthful answer.”

“The second best” type of question he can ask at oral argument, Breyer said, is one through which “you’re trying to tell your colleagues where you’re coming from.” The worst questions a justice can ask include making jokes which might inadvertently offend litigants — “Don’t do it,” he advised — and attempting to show they know more than the lawyers. “It’s not for you to show how clever you are or what you think,” he argued. “It’s to find out something.”

In his book, Breyer explores the Court’s history and draws from his experiences as a justice to argue in favor of a more pragmatic approach to interpreting the Constitution and federal laws, and to make the case against the increasingly favored methods known as originalism and textualism. When a word or phrase is unclear, he argues, a judge should go beyond the text and seek other sources for help. “You might look at, for example, what the purpose was of the individuals who wrote this,” Breyer explained to the audience. “What was the argument about? You might look at consequences. What will happen if we do it this way or that way?”

Minow asked Breyer to address a familiar criticism of his preferred pragmatic approach to judging. “Some people will say your view of purposes and consequences is losing, and it’s all politics.”

“That’s a big question,” he responded. “If you read the newspapers, you think it’s all politics.” He acknowledged that, when filling Supreme Court vacancies, presidents are besieged by political and interest groups pushing their chosen candidates, whose jurisprudential approach, however honestly pursued, will lead to “decisions that they think they’ll like politically.”

But he countered the concerns Minow surfaced by recalling a quote by the late Harvard Law Professor Paul Freund ’31 S.J.D. ’32, in which the constitutional scholar asserted that the Court “should never be influenced by the weather of the day but inevitably … will be influenced by the climate of the era.”

“And I think what Paul Freund said is the best explanation of the role of politics in the Supreme Court that I’ve read or heard,” said Breyer.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.