This story originally appeared in the Winter 2010 issue of the Harvard Law Bulletin. Judge Kassal passed away in 2019.

A few years ago, retired Judge Bentley Kassal ’40 began giving talks on his World War II experience: He was an air intelligence officer who participated in three invasions and was recognized by the U.S. Army with a Bronze Star for “meritorious service in direct support of combat operations.”

Last June, on the 65th anniversary of D-Day, at ceremonies at Colleville-sur-Mer in Normandy, it was French President Nicolas Sarkozy and other Allied leaders who did the talking. And it was the French government that recognized Kassal, bringing him and his wife to France for the ceremonies—and awarding him with France’s highest honor, the medal of the Légion d’Honneur.

In the summer, just a few days after he returned from France, Kassal invited a visitor into his Times Square office at Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, where he is of counsel. Kassal was a judge for 24 years in the New York courts—from the lowest to the highest levels—and he speaks in measured sentences, but when he talked about his trip, he was almost giddy.

“I’m still on a high—I don’t sleep as well as I did before,” he said. “Receiving recognition 64 years after the war ended, at the age of 92. I just can’t get over it. It was a tremendous experience.”

Kassal enlisted as a private in the Army in 1942. He graduated 17th in a class of 2,500 from Army Air Force Officer School, and in 1943, he arrived in North Africa and was assigned to air intelligence support for the invasion of Italy. Kassal landed on the beach near Gela, Sicily, and dug his first foxhole as the bombs started to fall. “It felt like living in your own grave,” he recalled.

Kassal planned bombing runs and advised American pilots on the vulnerabilities of the German Luftwaffe. He participated in two other landings during major invasions, in Salerno, Italy, and finally on Aug. 18, at St. Tropez, on the coast of Southern France—three days after the invasion of 250,000 Allied troops, which he had helped to plan. It was 70 days after the Allied forces stormed the Normandy beaches.

Last June, after ceremonies in Paris where the French minister of defense pinned the medal on Kassal’s jacket and kissed him on both cheeks, Kassal and the other newly decorated veterans arrived at Normandy. Above the beaches where 156,000 Allied troops had come ashore, they heard President Sarkozy, President Obama ’91, and Prime Ministers Gordon Brown of Britain and Stephen Harper of Canada deliver solemn tributes to the soldiers whose bravery led to Hitler’s defeat.

It was magnificent, Kassal said. “When it was over and the orchestra began to play our national anthem, I cried. I was so emotionally captured by the moment.”

As President Obama and Michelle Obama ’88 were on their way to the next event, to Kassal’s great delight, the president noticed Kassal’s HLS cap and stopped for a photo.

On the walls of his office in New York City hang photos of Kassal with famous people he’s come across, as a state assemblyman in New York and later as a judge—from Eleanor Roosevelt to President John F. Kennedy, and now the Obamas. But there are also the photos he’s taken himself. Since 1971, Kassal has traveled to 158 countries as a volunteer photographer for organizations such as Save the Children.

Kassal got his first camera when he was 5, and he believes he has a pretty good eye. But what he’s proudest of are the expressions he’s captured, like the determination of the boy soldier in Afghanistan: “You’ve got to wait for the right moment,” Kassal said.

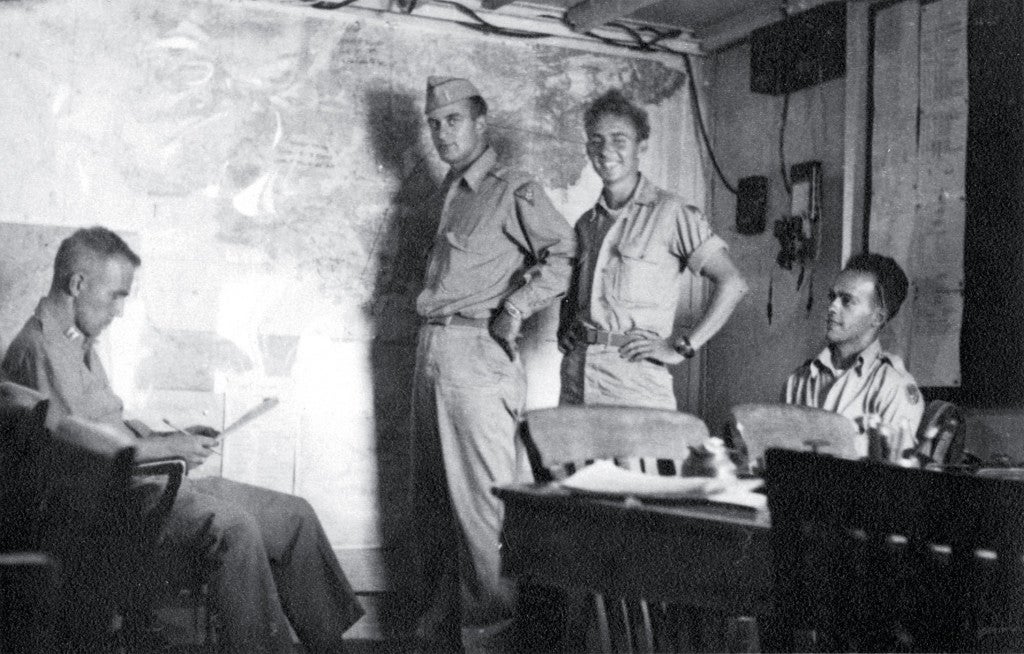

He did so during World War II. The talks he’s given on the war are illustrated with his pictures. Some document the effects of Allied bombing—from crushed army barracks to wrecked churches—but there are also the photos of people, like the German prisoners of war—boys that seem no older than 14, smiling disarmingly at the camera. In another image, French soldiers lead a line of prisoners away. “I’m sure they were all killed,” Kassal said. “Look at their faces.” He took a picture of one such victim in the South of France, a German soldier whose body dangled above a street where passersby stared.

After the ceremonies were over last June, Kassal and his wife spent two weeks traveling in the South of France. He photographed synagogues for the International Survey of Jewish Monuments, and while they were there, they took a detour to the village of Salon.

It was there that Kassal had been called on to accept the surrender of German anti-aircraft soldiers left behind as the German army retreated.

Kassal hadn’t received combat training, but with six men with carbines, he approached the farmhouse where the Germans were waiting. “I didn’t know what to do next,’’ he said, “but I imagined what John Wayne would do and I said, ‘All right, men, cover me.’”

“I didn’t know exactly what that meant, nor did they,” he laughed.

The German soldiers were either over 50 or under 16. But their commanding officer was a 27-year old lawyer, like Kassal.

“We conversed in English,” he remembered, and the officer told him that Hitler would still win. “I wanted to hit him,” Kassal admitted. Instead, he asked a question: “Did you ever think you’d be taken prisoner by a Jew?”

Kassal remembers the look of hatred on the man’s face as vividly as if he’d snapped his picture.