On Flag Day this year, when Irene Englund’s ashes were placed at Arlington National Cemetery, soldiers fired a rifle salute, a bugler played taps, and an American flag was presented to Englund’s daughter Julie.

It’s what you might expect to mark the passing of a veteran. Yet it took a daughter’s determination to win the right to this final show of respect for her mother and many other women who served their country.

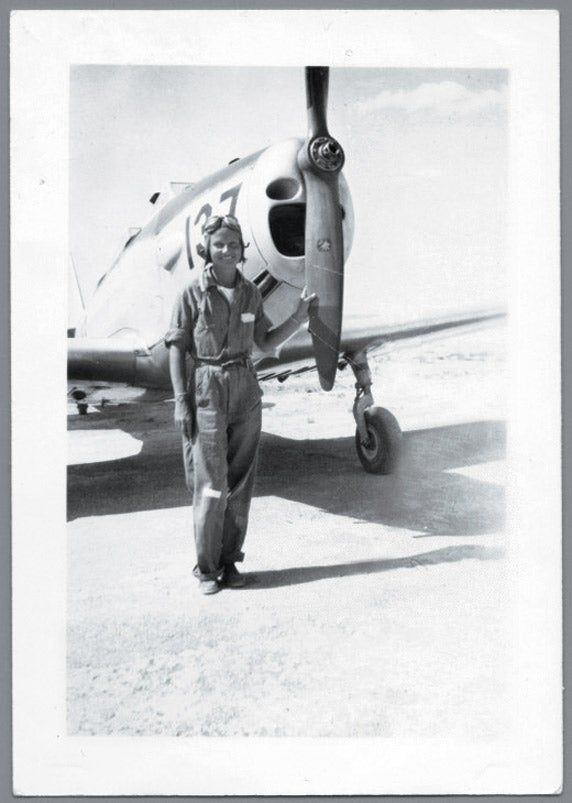

Irene Englund was a military pilot during World War II. She loved the speed and the power of the bombers. And later on in life, when she was married and raising a family, she kept a picture of her favorite B-24 bomber on the dining room wall like a friend from the past she didn’t want to forget. After her mother died in February, Julie Englund learned from Arlington National Cemetery that she and other Women Airforce Service Pilots were ineligible for military funeral honors, including an American flag.

Julie Englund, dean for administration at Harvard Law School, wrote an opinion piece on behalf of her mother and the 500 surviving WASPs, which appeared in the Washington Post and other papers. She celebrated the women pilots who flew domestic missions, freeing men for combat. In an interview with the Bulletin, Englund called them pioneers. The Army enlisted women to fly military planes for the first time, but the WASPs were made to prove themselves every step of the way, and they did, she says. From transporting patients to towing targets for novice gunners to testing new planes, they ended up taking on every kind of mission, except combat.

Yet in December 1944, the WASPs were dismissed to make room for male pilots returning from war. They went without any of the benefits of the GI Bill or even bus fare home, says Englund. Women did not return to the cockpit of military aircraft until the 1970s. In 1977, Congress granted the WASPs veterans’ status. Yet Arlington National Cemetery maintained that these women were ineligible for the same honors as male veterans.

After her article appeared, Englund received hundreds of letters and e-mails. Women and men sent their condolences, their advice, their outrage–and, to make up for what the military would not provide, they sent flags. They came from members of Congress, from veterans. They came from soldiers who were fighting in Afghanistan. Some people promised to raise their flags at home on the day of the ceremony, and others asked permission to attend, to honor her mother since the military would not.

Little more than a month after Englund’s article appeared, the Army changed its policy regarding WASPs and 36 other groups formerly excluded from funeral honors at Arlington.

On Flag Day, among those attending Irene Englund’s funeral were 12 elderly women pilots there to recognize the passing of one of their own. Julie Englund says it is only right that these veterans who paved the way for women in military aviation will get the recognition they deserve.