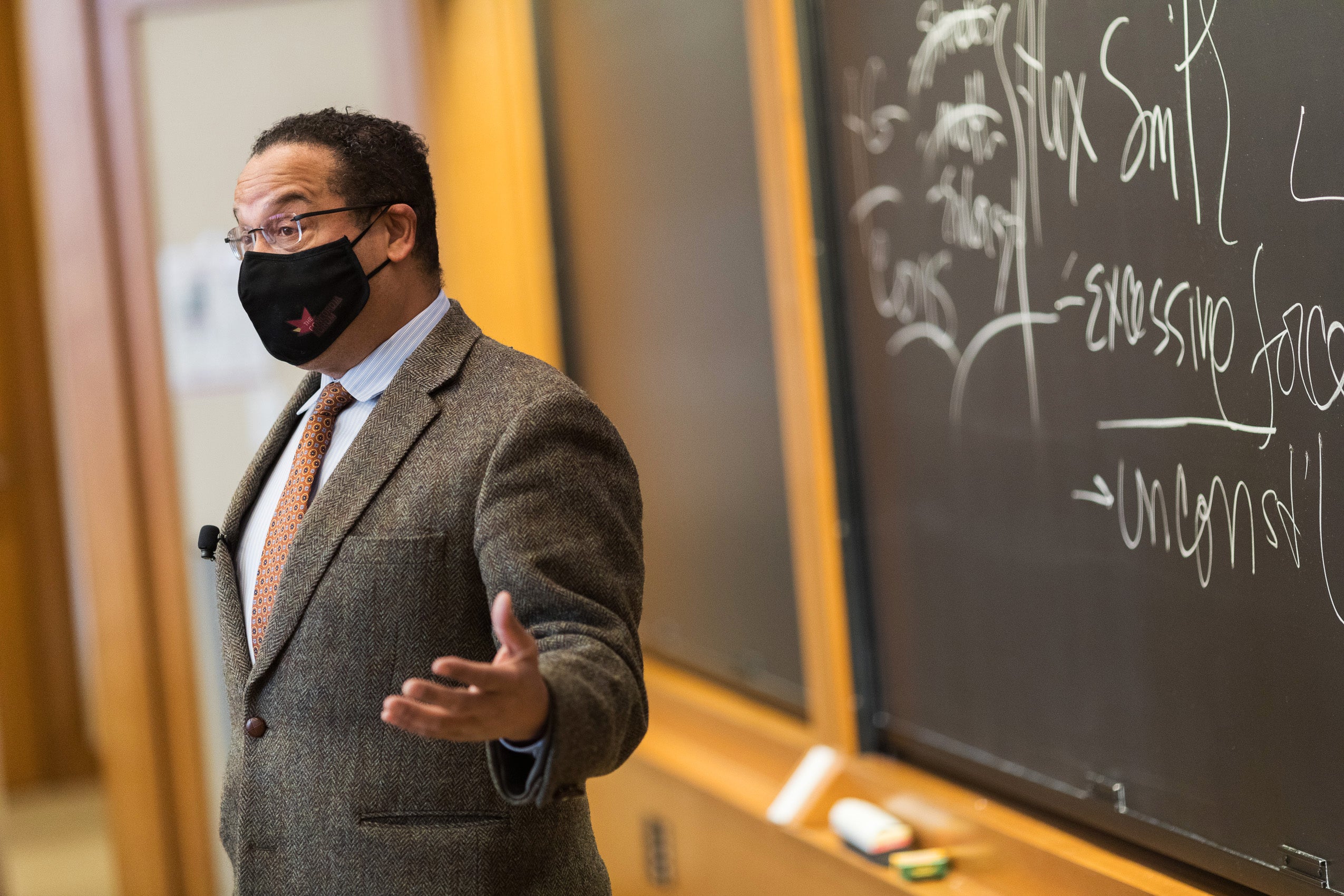

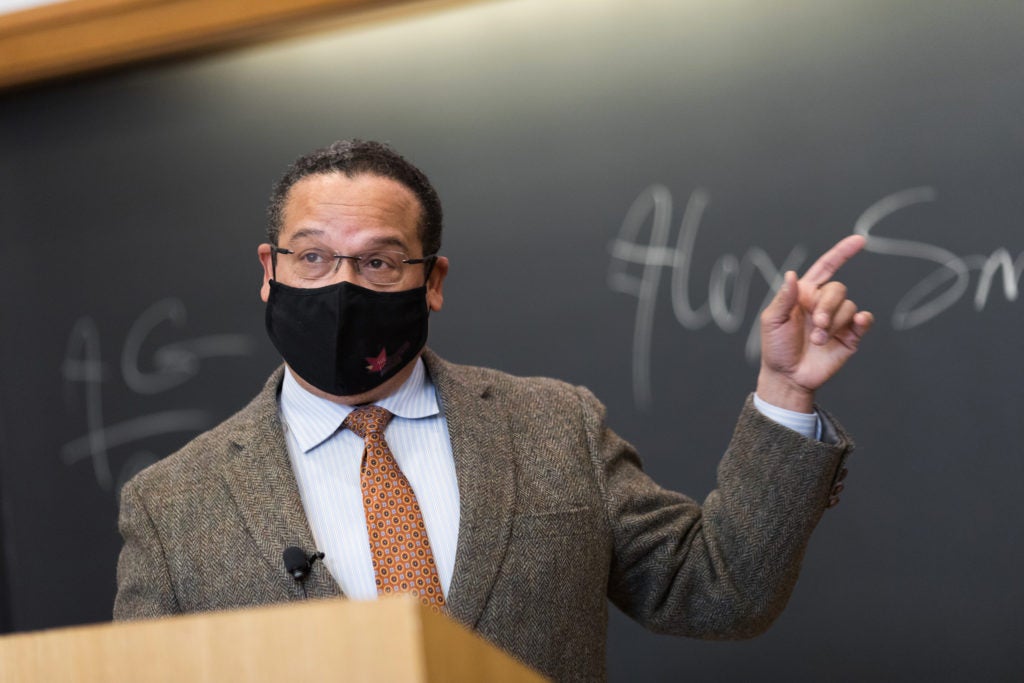

It’s no accident that the George Floyd murder trial, State v. Chauvin, was a powerful emotional experience for many Americans, Minnesota attorney general Keith Ellison told a Harvard Law School audience on Friday. “Don’t let anyone tell you that a case is not a theatrical presentation,” he said. “You’re damn right we wanted to strike an emotional chord.”

During a lunchtime talk, Ellison outlined the factors, legal as well as theatrical, that went into his prosecution of the case. And he noted that taking the case was by no means a safe decision, urging the students to take that as a lesson. “I got some very smart political advisors that said ‘Look, if you take this case, you’re probably going to lose, because that’s what always happens. And if you do win, you’re going to be the guy that convicted police officers. This is not a good political move.”

Turning to the students, he said, “If there’s one thing that I hope all of you do in your legal career, it’s that you don’t make a decision based on what pays the most, or what looks the best, or what Mom and Dad want you to do — but on what you feel that you should do with your short time on this planet.”

In explaining his team’s approach to the Chauvin case, he urged students to repeat the word “theme” — a key factor in presenting any case, but especially this one. “You’ve got to have a way to link it all together, so it makes sense in the mind of a jury.”

(Our team) knew that because juries tend to resolve all doubts in favor of the police, that we needed to block every hole.

Part of this, he said, was to consider the impact of witness testimony instead of relying too much on video evidence. Thus, they chose as their first witness 911 dispatcher Jena Scurry, who gave dramatic testimony about watching Floyd being pinned to the ground during the distress call. “We had a very multicultural group. Three 17-year-old girls, two white and one Black. We had senior citizens, and a firefighter who was just out for a walk that day. And they’re all screaming ‘Check his pulse’ … We get these witnesses, and it feels like we’ve got the attention of the jury.”

Equally important, he said, was anticipating the defense’s arguments. “We knew that because juries tend to resolve all doubts in favor of the police, that we needed to block every hole.” That meant bringing in experts to confirm that Floyd did not experience “excited delirium” (a medically-controversial term for extreme agitation), and that he didn’t have an enlarged heart or a critical amount of methamphetamine in his system — all arguments that wound up being made in Chauvin’s defense.

Ellison said the trial changed his mind in two ways: First, he’d initially been opposed to having it shown on TV. “I brought motions to not allow it, and I was wrong. The educational value of people watching it was so great, as long as you don’t show the jury or vulnerable witnesses.”

Second, he fully expected a not guilty verdict. “I didn’t know how willing the jury would be to commit to the verdict sheet what they saw on the witness stand. … We still have implicit institutional bias, but we have more people who are willing to see it for what it really is and say no to it. There’s a lot of lessons to be learned, and we are still unpacking them all. [But] I can tell you, one case does not mean that we have a new system.”

He named the Congress’s failure to pass the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, police reform legislation which was approved by the House of Representatives but failed to overcome the threat of a filibuster in the Senate, as a recent setback. “That really broke my heart,” he said.

In a question and answer period near the end of the program, one Harvard Law student asked about Ellison’s statement that he broke the “blue wall” by prosecuting police corruption in the Chauvin case — How, the student wondered, did that affect the AG’s office’s relationship with local police afterward? “I think we’re good,” Ellison said, pointing out that 14 police officers had already written a letter objecting to Floyd’s killing.

Yet sometimes, Ellison admitted, things weren’t that cut and dried. He cited the case of Kimberly Potter, the former Minneapolis police officer who was convicted of manslaughter after shooting a Black man at a traffic stop, claiming she accidentally drew her gun instead of a Taser. “She was well liked by her colleagues; they felt it was a mistake. I said yes, it is — but some mistakes, if they have lethal results and are contrary to your training, are crimes. … But I can tell you, it was damaging to the morale of that department.”

Police officers are just like the people in this room; they span the human experience. Do you want to work with someone who is incompetent, racist, or a bully? Neither do they.

Another student, who was also a Minnesota native, asked about possible blowback from the Chauvin trial, particularly a reported rise in violent crime since the verdict. In response, Ellison emphasized that he is pro-police and has never been in favor of defunding — but that calling out isolated cases of brutality ultimately makes a community safer.

“As a criminal defense lawyer of 16 years, I know for a fact that some people who make their lives out of committing crimes know when the trust between police and the community is bad, and they want to operate in those areas,” Ellison said. Further, he argued that most police officers would support anti-brutality efforts. “Police officers are just like the people in this room; they span the human experience. Do you want to work with someone who is incompetent, racist, or a bully? Neither do they.”