The opening event of Harvard Law School’s Bicentennial summit was one for the history books. Gathering Thursday afternoon at Sanders Theater were six Supreme Court justices (five current and one retired)—technically enough to swing a case, and the largest such Harvard gathering on record. The last comparable event on campus was in 1955, when five justices were present to celebrate the birth anniversary of Chief Justice John Marshall. But this time all six of the honored guests were HLS alumni: Neil Gorsuch ’91, Elena Kagan ’86, David H. Souter ’66, Stephen G. Breyer ’64, Anthony M. Kennedy ’61, and Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. ’79.

In a roundtable discussion with Dean John F. Manning ’85, the justices shared memories, advice and more than a few priceless anecdotes. And they confirmed that some Harvard experiences are the same across generations, like the demand for hard work.

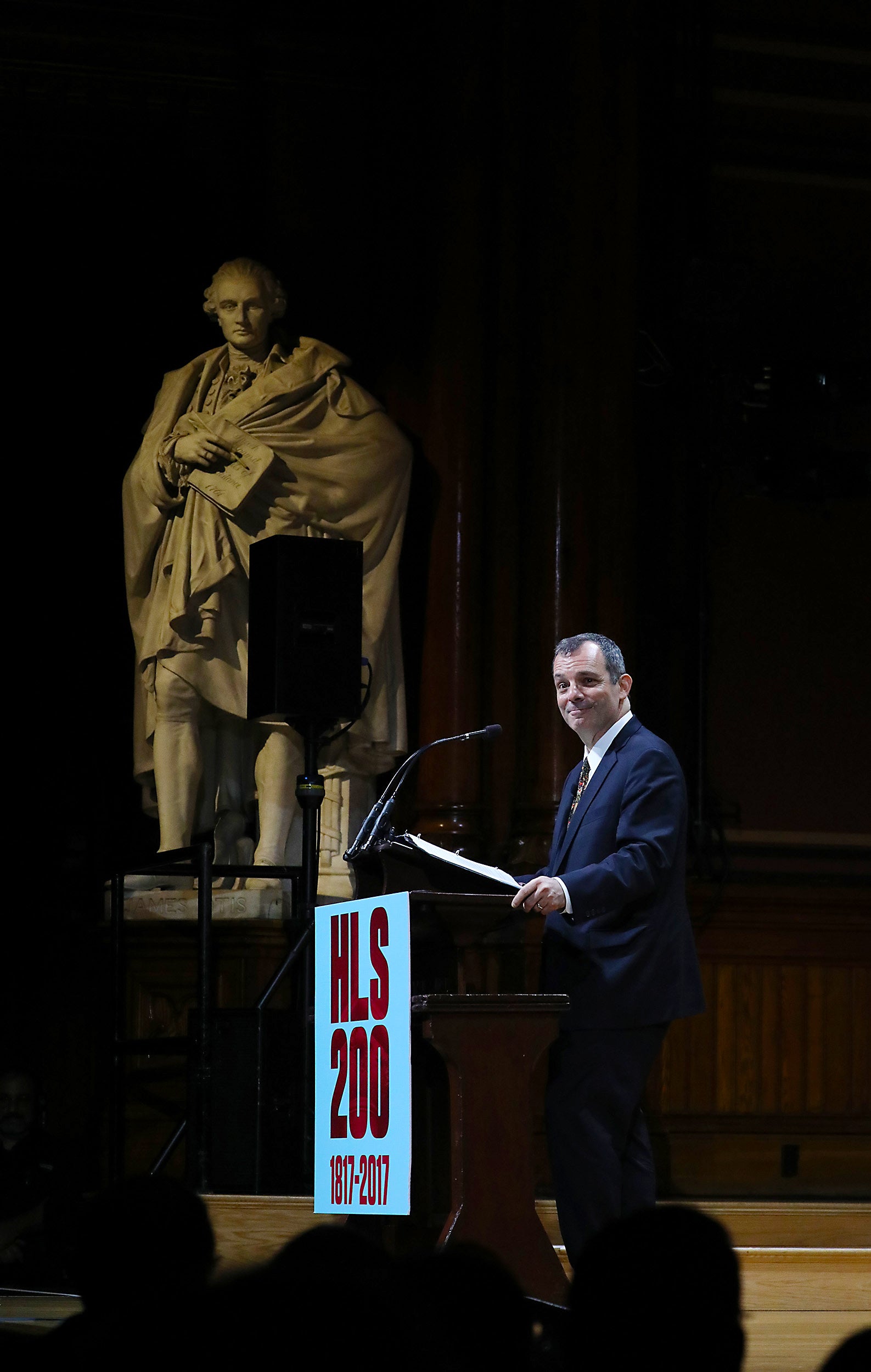

The six arrived at Sanders with proper ceremony, as the Harvard Band and a bagpiper played outside Langdell before a procession to Memorial Hall. Professor Richard Lazarus welcomed the crowd and introduced Harvard President Drew Faust, who gave an overview of HLS history: “It’s hard to picture an afternoon two centuries ago, when HLS had two faculty and six students. And who could have predicted that the same institution that denied [civil rights lawyer and activist] Pauli Murray admission in 1944—not because she was black, but because she was female—would elect a black female law review president in 2017?”

Roberts gave a brief introductory talk invoking four of HLS’s earlier celebrated alumni: Oliver Wendell Holmes 1866, Louis Brandeis, Felix Frankfurter and Learned Hand. “[They] had an oversized influence on the law. And while they were different in many ways, two common themes come to the fore: The central importance of free exchange of ideas, and the need for intellectual humility. That last word isn’t the first one that you think about when talking about Harvard Law School. But remember it was Holmes who said that doubting one’s principles is the mark of a civilized man.”

Manning noted at the outset of the roundtable with the Justices that he would focus on three topics—their Harvard education, early professional experience, and Court life—with a “lightning round” at the end. As the youngest justice on the panel, Gorsuch opened the first category by remembering his first assembly at Sanders: “The Dean addressed all the first-year students, and I was scared to death.” Asked how long that stayed with him Gorsuch shot back, “I’ll let you know.” Kagan recalled a similar experience: “I got called on in my very first class, and raked over the coals. But then I could say, ‘Fine, I got that over with’. The worst had happened and I could relax.”

The panelists were also asked which courses and professors had left the greatest mark on them, and in a few cases named each other. Just after Breyer singled out an antitrust course, Kagan added, “I also had a favorite antitrust professor, and you just heard from him.” (Breyer was on the HLS faculty before his appointment to the federal bench in 1994). Roberts in turn named Kagan as one of HLS’ greatest deans, and Gorsuch cited his experience clerking for Kennedy. And Kennedy recalled one of his own mentors, the feared and admired professor Henry M. Hart. “His class was at 12pm. We called it Darkness at Noon.”

When Manning asked what best prepared them for the Supreme Court, Breyer, invoking advice given to him by Justice Harry Blackmun ’32, replied that nothing really does—but that his work with Senator Ted Kennedy taught him the difference between taking credit and getting results. “He always used to say that if an idea is good, there’s enough credit to go around—and if it’s bad, who wants it?”

Kagan said that teaching gave her the best preparation. “When you teach, you’re trying to explain really complicated things to people who want to understand them, but don’t have the knowledge then and there. That’s not far from what happens when we craft opinions.” Roberts said that he learned the most by working for private clients. “To my right would be a representative of the most powerful force in the world, the government of the United States. That force wanted to do something with my client. All I had to do was to convince five lawyers that the government did not have the right to do that, and I won. That’s when I really learned what the rule of law meant.”

On a lighter note, Manning asked what the panelists would be doing if they weren’t on the Court. Roberts, Kagan and Souter all saw themselves as history professors, and Kennedy as a literature professor. Only Breyer and Gorsuch went in the opposite direction, respectively to play baseball and to work as a fly-fishing guide. Manning also asked which historical figures they’d most want to work or have dinner with. Roberts named John Marshall as the justice he would most have liked to work with, calling him “the most significant figure in US history who was not President … His ability to exercise influence over the other justices who were living in the same town house through the force of his personality and the persuasiveness of his reasoning was extraordinary.” Roberts lauded him as a brilliant thinker who had “a mind that could see all of the bounds of the problem at once, and then sort through it.” He also praised the eloquence of Marshall’s writing, particularly in Marbury v. Madison: “He was a brilliant writer, people don’t realize that. If you pick up Marbury v. Madison, it doesn’t read like the late 18th century. There are no ‘whereas’s or ‘heretofore’s … an intelligent layperson can read it.” Kennedy echoed Roberts’ sentiments, saying of Marshall: “He had a vision of a country that would be unified by this magnificent Constitution–a Constitution that can endure, and that must endure, for ages.”

Others picked Brandeis or Holmes to work with, but the dinner choices were more diverse: Kennedy picked John Marshall and, Kagan picked Thurgood Marshall (for whom she clerked) as a great raconteur; and Roberts chose William Howard Taft “because he’s an underrated thinker. And you know you’d get a lot of food, and it would be good.”

In the closing “lightning round,” Dean Manning asked the justices to raise their hand when they recognized a little-known fact that he’d dug up about their life or career history. The audience learned that Gorsuch’s family raises goats, that Breyer was an Eagle Scout at age twelve, that Roberts used to make daily trips to Baskin-Robbins in Harvard Square for ice cream, that Kagan never uses contractions in her opinions for the Court, but uses them in her dissents, and that Souter and Breyer are regularly mistaken for each other. And they heard that Kennedy was caught attending a Red Sox game the day before an important tax exam (It was 1960 he explained, and the last chance to see Ted Williams). The person who caught him there: Erwin Griswold, the dean of the law school at the time.

Souter revealed that he had been rushed to University Health Services in his second year of HLS, after slicing his hand in a mock sword duel. “It was a way to pass the time,” he explained to laughs and applause. After this mishap, Souter ordered cream cheese and caviar sandwiches from the then-popular deli, Elsie’s, for everybody in the emergency room. That’s not a piece of American legal history that you’re ever likely to hear anywhere else.

Related coverage

Wall Street Journal: With Little Dissent, Supreme Court Justices Toast Harvard

CNN: Supreme Court justices let down their robes at Harvard

Boston Globe: Supreme Court justices reminisce about their Harvard days

Washington Post: How many Harvard law school grads does it take to make a Supreme Court?

ABC News: Supreme Court justices celebrate Harvard Law bicentennial

WBUR News: Supreme Court Justices Celebrate Harvard Law Bicentennial

Harvard Magazine: “Debate and Doubt”

NPR: Harvard At 200: Justices Look Back On Their Law School Days — And Beyond