Excerpted from “Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality” by Tomiko Brown-Nagin, Dean, Harvard Radcliffe Institute, Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law, and Professor of History.

In the spring of 1963, the eyes of the nation turned to Birmingham, Alabama, then known as the home of a thriving iron and steel industry. In April and May of that year, Birmingham, a land trapped in a “Rip Van Winkle” slumber on issues of race, and the nation’s “chief symbol of racial intolerance,” according to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., became a flashpoint in the Black struggle for equality.

In his inaugural address, George C. Wallace, elected governor of Alabama in 1962 on a pro-segregation and states’ rights platform, rebuked the civil rights movement. “I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny,” the governor said. He vowed to maintain “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor, Birmingham commissioner of public safety and an unapologetic racist who controlled the police and fire departments, also vowed to defend white supremacy. The civil rights movement had encountered two of its fiercest foes.

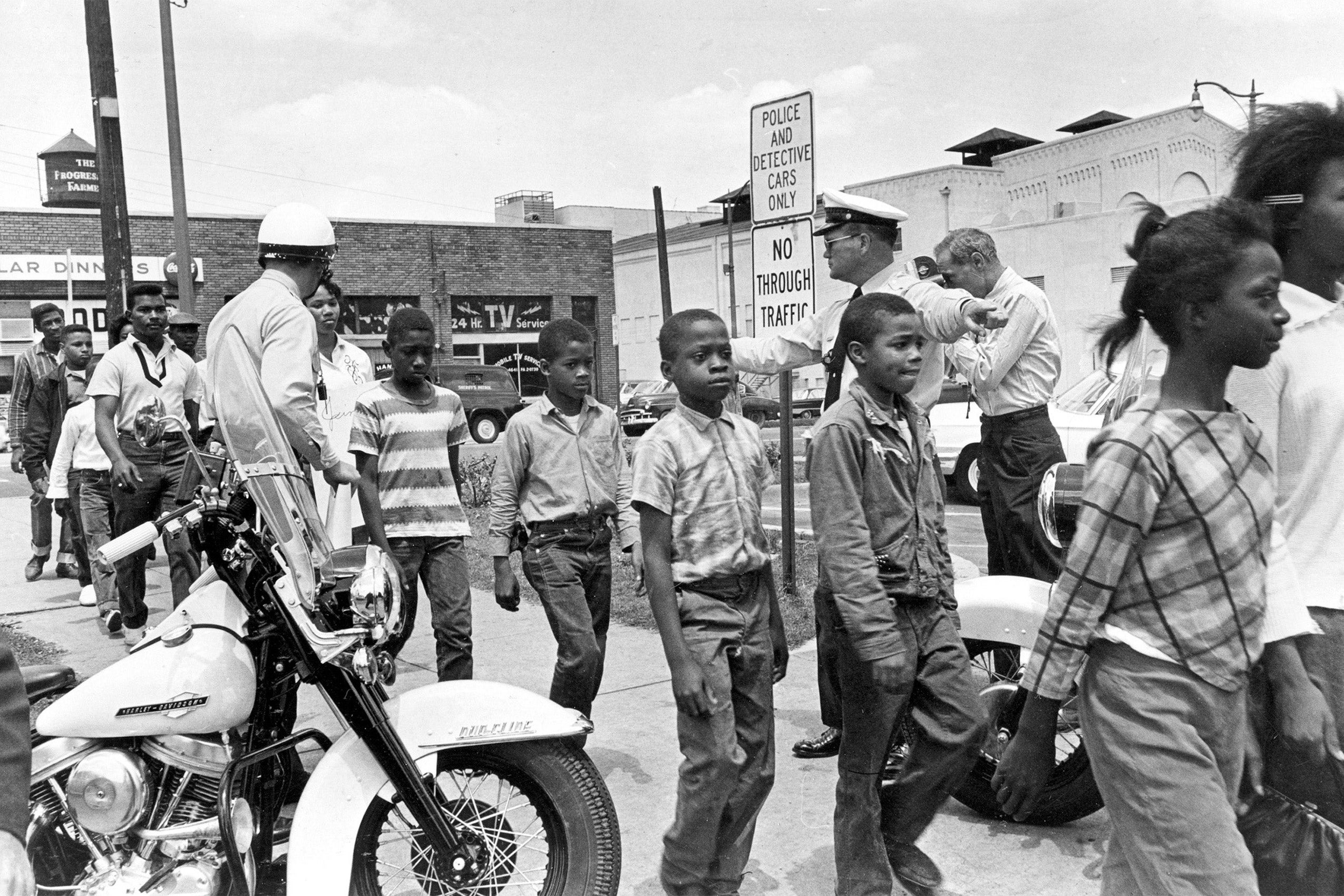

For five weeks, beginning April 3, 1963, King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and a coalition of grassroots activists led by Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), a “firebrand” known for his invincible courage and confrontational leadership style, staged a mass civil disobedience campaign and squared off against the ardent segregationists. Through sit-ins, demonstrations, and boycotts, protesters sought to expose the cruelty of Jim Crow and draw attention to the value of Black purchasing power; ultimately, they hoped to desegregate the city and increase Black employment opportunities.

The campaign was the brainchild of Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker of SCLC, who called it “Project C.” The “C” stood for “confrontation” — nonviolent confrontation. “If we could crack Jim Crow in Birmingham, known as the nation’s most segregated city,” Walker said, “then we could crack any city.” Shuttlesworth, who had been brutalized and nearly blown to bits in retaliation for his efforts to desegregate Alabama’s schools and buses, agreed that a successful drive against Jim Crow in Birmingham would reinvigorate the movement. He warned that the campaign would be extremely dangerous, but could be extremely rewarding: “You have to be prepared to die before you can live in freedom,” he said.

In its early days, the meticulously planned campaign had generated little community support; many middle-class Blacks actively opposed it, and casual observers largely ignored it. “[O]ur community was divided,” King conceded. Small numbers of activists — a mere seven at a local cafeteria and eight at Woolworth’s — turned out to stage sit-ins on April 3. Instead of contending with the demonstrators, workers took the day off. Only a smattering of the protesters were arrested. Even Shuttlesworth generated little enthusiasm when he led a sit-in on April 6; only a few dozen people came to join him.

The very next day, on April 7, there was another small demonstration involving about 20 people, an embarrassingly small number, but this time it ended differently. Connor unleashed police dogs and firehoses on the peaceful and prayerful protesters marching toward the town center. In the chaos, several dogs pinned a 19-year-old Black man to the ground, and officers kicked the man — a bystander uninvolved in the movement — as he lay there helpless. News reports and public attention highlighted this incident of police brutality. The spectacle grabbed the attention of those who previously had ignored the protest, and SCLC found the “key” to motivating the Black community and garnering press coverage: demonstrations that precipitated violent confrontations with Connor’s police.

A few days later, on April 10, King, Shuttlesworth and the other ministers leading Project C defied a court order, which had been a part of city officials’ plan to halt the movement. First, officials refused to issue the protesters a permit to parade; next, they secured a court order enjoining unlicensed protests. King called the injunction nothing more than a “pseudo-legal way of breaking the back of legitimate moral protest.”

King and his movement had come to a crossroads. Out of respect for the U.S. Supreme Court’s stand against segregation in Brown v. Board of Education and other federal court decisions that aided the movement, King had vowed never to violate a federal court order. At the same time, the ministers concluded that the movement owed no deference or loyalty to state and local courts, where, more often than not, proud racists presided.

In the face of the command to stop engaging in civil disobedience without a permit, King held a press conference. “Injunction or no injunction,” he said, “we are going to march tomorrow. I am prepared to go to jail and stay as long as necessary.” Unlike federal courts, “recalcitrant forces in the Deep South,” King said in his statement, deployed the law “to perpetuate the unjust and illegal system of racial separation.” In light of the corruption of the judicial system, SCLC would go on with Project C, “out of great love for the Constitution notwithstanding the court’s demand.” Read more on the Harvard Gazette

Related

Looking back on ‘the future’: The Rev. Dr. King at the Harvard Law Forum