The mass institutionalization of people with mental health, intellectual, and developmental disabilities isn’t ancient history — and it’s not even history, argues Alex Green, a visiting fellow at the Harvard Law School Project on Disability.

In his new book, “A Perfect Turmoil: Walter E. Fernald and the Struggle to Care for America’s Disabled,” Green recounts the life and career of Walter Fernald, a late-19th and early-20th century physician and educator whose work with people with disabilities left a complicated, and enduring, legacy.

“An extraordinary propagandist politician” in addition to a renowned reformer, Fernald reshaped the state-run Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded by rethinking the causes and treatment of mental and intellectual disabilities, Green says. Fernald, who believed that people with disabilities had a right to learn like everyone else, created the first modern special education program and promoted policies that were emulated across the United States.

But Fernald also became one of the country’s leading supporters of eugenics for a time, before again reversing course, says Green, who is also a fellow at Harvard Law’s Program on Negotiation. Fernald would spend the final portion of his life repudiating that inhumane school of thought and advocating for deinstitutionalization.

Yet by 1967, more than 200,000 people with intellectual and developmental disabilities were locked away in state-run asylums — many of which subjected inmates to horrific physical, mental, and sexual abuse, Green says. Even Fernald’s school — which, perhaps ironically, was renamed for him a year after he died — became known for appalling human rights abuses, finally closing in 2014.

Green became intrigued by Fernald when he stumbled across an old front-page Boston Globe article mentioning that the Massachusetts governor had ordered the state’s flags lowered to half-staff following Fernald’s passing. “I thought, I’ve never heard of that for another educator or a doctor. And that set me down the path of everything that followed.”

Green didn’t think he’d find many existing records about Fernald or the infamous institution that eventually bore his name. “I went to the Massachusetts State Archives in 2015 expecting to find nothing, and instead, was greeted with the response that, no, we have 65 boxes of Walter Fernald’s correspondence alone.”

There were a few problems accessing the materials — big ones, Green says. Of the more than 250,000 pieces in the collection, he says, “Everything was out of order by page, every single page out of order.”

And that’s if Green could access them at all. “Massachusetts has some of the most restrictive medical privacy laws in the United States, and every single page had to be pre-read and redacted for any inmate’s name or any information whatsoever,” he explains.

With an attorney’s help, Green was able to reach a settlement with the state, which found a way to grant him access to the entire collection while still ensuring patient privacy. And once he began reading the materials, Green says he knew he wanted to write about Fernald, a flawed man whose legacy has been tarnished — if not forgotten — but who contributed important advances in the education of people with disabilities.

“That was enough to shatter myths that were widely in the literature about why institutions for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities were originally developed, and how they came to be what they were. And I thought, I have to keep going.”

In an interview with Harvard Law Today, Green shares more about Fernald, what Green hopes readers take away from his story — and why it still matters today.

Harvard Law Today: To understand a bit about why Walter Fernald was an important figure, it might be helpful to set the scene. What kind of life did people with intellectual, mental health, or developmental disabilities lead in the U.S. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries?

Alex Green: I think any time where there’s rapid change, people with intellectual, developmental, and mental health disabilities are often thrust into more difficult situations. After the Civil War, America had this massive industrial boom and expansion into the West, a large amount of immigration, and in that, conditions were incredibly poor for everybody — and poorer still for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, who were widely reviled by society and had few opportunities to get an education and try to lead a life like anybody else.

From the thousands of letters I’ve read, the conditions were bleak to the point of desperate for families with disabled children. To have a child with significant disabilities meant that you would have to choose between going to work and leaving them in incredibly vulnerable positions, or staying at home and starving. And there was no real widespread belief the state had much of a role to play in that, and so people ended up in poor houses and on poor farms and in situations where I think abuse was rampant and conditions were not great.

In 1848, when Samuel Gridley Howe created the school that would later become the Fernald State School, the goal, which was so radical at the time, was that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities can learn and deserve an education and have a right to it the same as anyone else would have access to a public school. But by the time Walter Fernald arrived at the school, that vision was kind of ailing. The school was not in good shape.

Fernald had young energy and an extraordinary capacity to take large amounts of information in from all over the world and synthesize them and put them into practice in ways that people hadn’t seen before. That made the educational program that he developed when he moved the school to Waltham in the 1890s something that people came from the world over to try to see and learn from, as did the design of the campus. The whole approach that he took changed — but that’s the beginning of the story, at least.

HLT: What was Fernald’s initial approach to the school?

Green: First, I should say that the language in a lot of his writing can sound really horrible. It’s outdated, ancient language, and it’s brutal in a lot of instances. Fernald himself was an extraordinary propagandist politician, along with being a very good doctor and educator, and so he would often talk to audiences by meeting them where they were, and that meant mimicking a lot of very brutal language about their conceptions of what a disabled person was. He thought that we had to accept that society was not being good to its disabled people, especially disabled children, and that for that reason, he felt that they deserved to be kept away from the prying eyes of people who would pick on them and make fun of them and get the education they deserved out in Waltham.

That education was a very intricate and extraordinarily well-developed mixture of fundamental topics, such as reading, writing, and math, combined with vocational education and things like woodworking or dressmaking or things that could get you a job. The way he put that together surprised people, and they saw how they could provide that education to kids with disabilities in their own schools. That kind of patience and dedication toward disabled kids as deserving intentional and focused education and medical care was unique.

Fernald also understood that people need to be able to name what they’re seeing. It’s no accident that in the 1890s, he also creates the first outpatient clinic of its kind in the world for kids with intellectual and developmental disabilities. It flies in the face of the myth that came later, that his only life goal was to institutionalize everybody. I think he really understood that people needed to know what kinds of supports they could get and where they might exist, and that they needed to speak with someone with some expertise on this. He had seen a lot of cases and could give them some answers — as rudimentary as they were in the 1890s. His gift was in putting things together in incredibly clear and organized and effective ways that people could begin to make sense of, rather than just staring at disabled people as though they were some kind of monstrous “other.”

“This is not past. There are people all around us who have been institutionalized for substantial portions of their lives in large scale institutions. It is shocking.”

HLT: Despite Fernald’s early thinking, your book probes how he is later increasingly influenced by the growing eugenics movement. Can you tell us more about that?

Green: Fernald begins to slip into a deepening prejudice for a few reasons. I think one is that he’s afraid that that as some of the students get older, they don’t have a safe place to return to, and he starts finding ways to keep them around the institution. But that, of course, can very quickly slip into mass institutionalization for long periods, sometimes including life.

And Fernald also was disabled — he had extreme bouts of depression that sometimes set him out for months at a time. I think that contributed to what he later described as growing pessimism, which may have put him in the perfect mindset for eugenics as it hit the United States in the early 1900s. I think he thought eugenics helped make sense of something that he was wondering about at — the idea that maybe some people’s disabilities were expressed as delinquency, as crime, as mischief, as sexual promiscuity, and that that actually was an expression of disability in itself.

HLT: How did these new ideas impact the institution itself?

Green: All this sent him down about a 10-year long crusade to build out that idea in highly influential ways, and to use it to flip his original idea on its head. No longer was he interested in protecting disabled people from the outside world — he was interested in protecting the outside world from disabled people. His ideas are the underpinning of the concept of the “moron” when it was first introduced by Henry Goddard, and that’s no accident. The phrase that Fernald used for the same group of people was “defective delinquents.”

HLT: But then Fernald’s thinking evolves yet again. Why?

Green: He had fallen hard into eugenics because it provided him, as someone who was obsessed with organization and classification and systems of human behavior, an easy answer. He becomes one of the leading figures in the United States pushing eugenics. But he’s also constantly tinkering with ideas, interrogating them and playing with them and asking questions.

And he has an extreme disagreement with the other eugenicists that begins as a disagreement over sterilization. They want to not just segregate so called feeble-minded people for life — they want to sterilize them. Fernald is morally opposed to this with every fiber of his being, and that argument starts to balloon out. It makes him ultimately question everything that the eugenicists, including himself, have put forward, and start going back to test whether those claims have any validity. And what he finds is that they absolutely don’t. And that begins an almost decade-long period of him really trying to pull educators and doctors and leaders around the country back out of eugenics and toward a more compassionate view, much like the system that he started with, of small institutions at most. He wants to go back to making sure communities are good to their disabled people.

HLT: Ultimately, as you say, Fernald had a change of heart, but the country didn’t. Eugenics continued to flourish — in fact, Buck v. Bell, a landmark Supreme Court decision that upheld the constitutionality of a Viriginia sterilization law, was decided in 1927. It has also never been fully overturned. Why wasn’t Fernald successful in changing peoples’ minds?

Green: The answer that’s right in front of us is a hatred of disabled people. The fact is, that the people around him were not committed to dismantling this system and had not put disabled people first and foremost in their work. They were careerists. They were people who cared more about their own attainment as doctors and psychologists, as social workers and teachers and medical attendants, and disabled people continued to come last, and have continued to come last for the century after that.

What makes Fernald unique is that he really did put disabled people front and center, and we can see how he did that in ways that are incredibly revolutionary for their time, including leading the first successful legal challenge against forced sterilization in America.

But I think by the time we got to the post-war period where the institution was named for him, probably nobody knew anymore that he had really wanted. He had been so clear that he wanted to “decentralize the institution,” by which he meant radically scale it down to almost nothing and make it a community resource hub. But the simple fact is that disability is it at odds with our ideas about the American dream, about the idea that you work hard and then you succeed, and you get your rewards, because many of us cannot work in the conventional ways that nondisabled people can, and faced with a group of people who don’t fit with the vision of that myth, non-disabled Americans have ruthlessly taken every opportunity over the last century and beyond to try to push disabled people back out of sight, because we don’t fit with common notions of efficiency or cosmetic beauty or other things we value most in society today.

HLT: What can we nonetheless learn from Fernald’s commitment to his ideals, particularly later in life?

Green: I think it should give us all extraordinary pause that so little has changed since 1924. In terms of innovative ideas about how to create a more equal and just society, the laws have not kept pace. What we can take from it is that we have an extraordinary amount of work to do at the individual and local level, as much as at the big governmental level, to bring down the barriers that put up to segregate disabled people, to abuse disabled people. I think you can judge a democracy on almost all its merits based on how its disabled people live, because we are the ones who most need that kind of communal solidarity that democracy is supposed to represent. We are least able to engage in the fantasy of rugged individualism.

And right now, I don’t see how we’re not failing. Writing this book has been an attempt to prove with certainty from the historical legal record that the things disabled people describe as longstanding practices to abuse us are not up for debate.

HLT: What issues do we need to be paying attention to today, in your view?

Green: First, I think that we must understand that any form of segregating disabled people should be seen as an extreme act and almost never done. We cannot be an institutional society and be a just and equal society for disabled people. And unfortunately, last few years, what we’ve seen is a move toward mass institutionalization, again, rather than away from institutionalization, along with a host of other segregationist ideas about disabled folks.

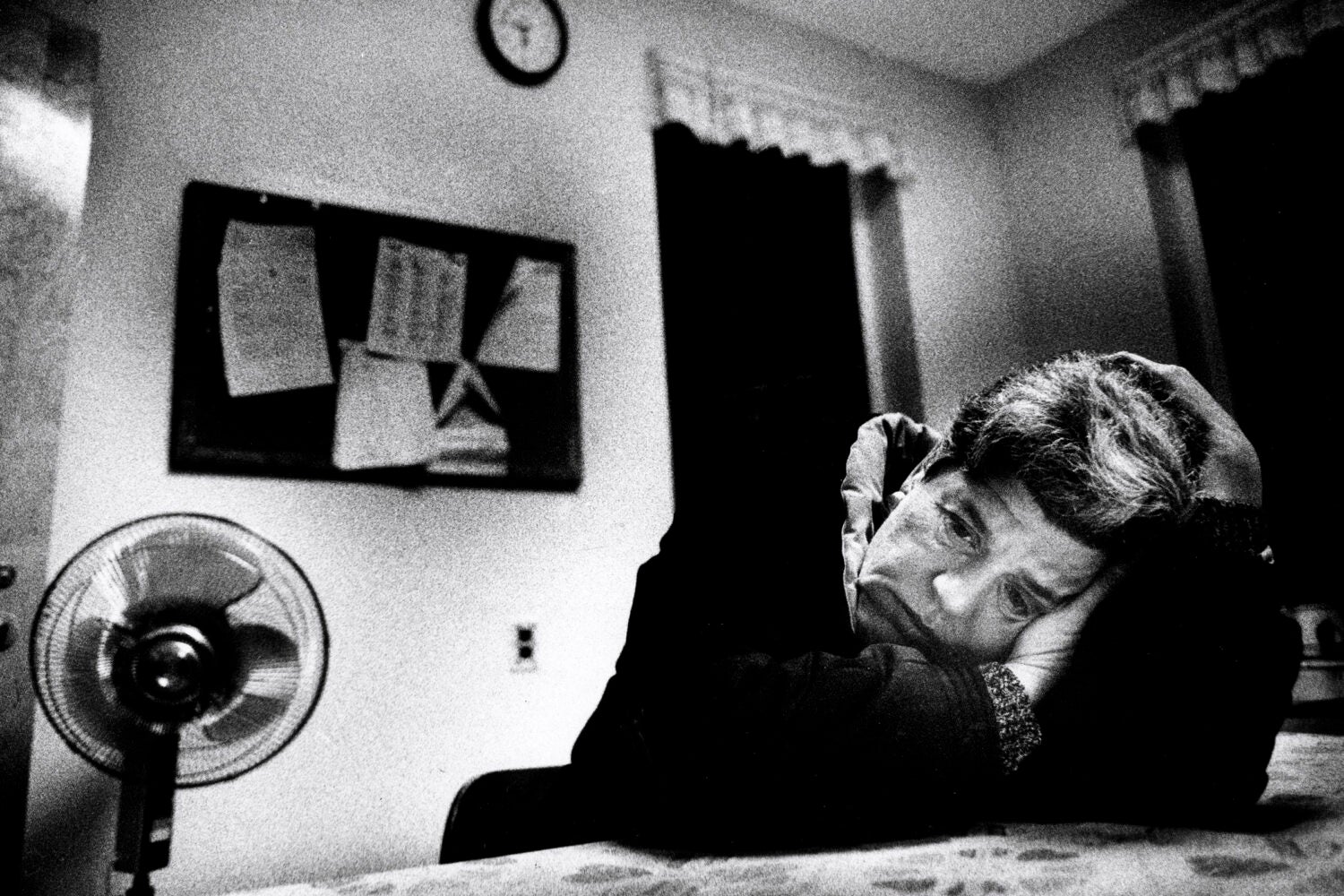

There is still so much work to be done. I was prepping a group of intellectually disabled folks for a hearing that we were all going to be at, and I asked this group, What’s the main message you want the legislators to know? And without skipping a beat, one of the three folks said, ‘We’re not dead. People who have lived in institutions are still alive, for God’s sake, and people treat us like ghosts.’ I still think of that every day. This is not past. There are people all around us who have been institutionalized for substantial portions of their lives in large scale institutions. It is shocking.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.