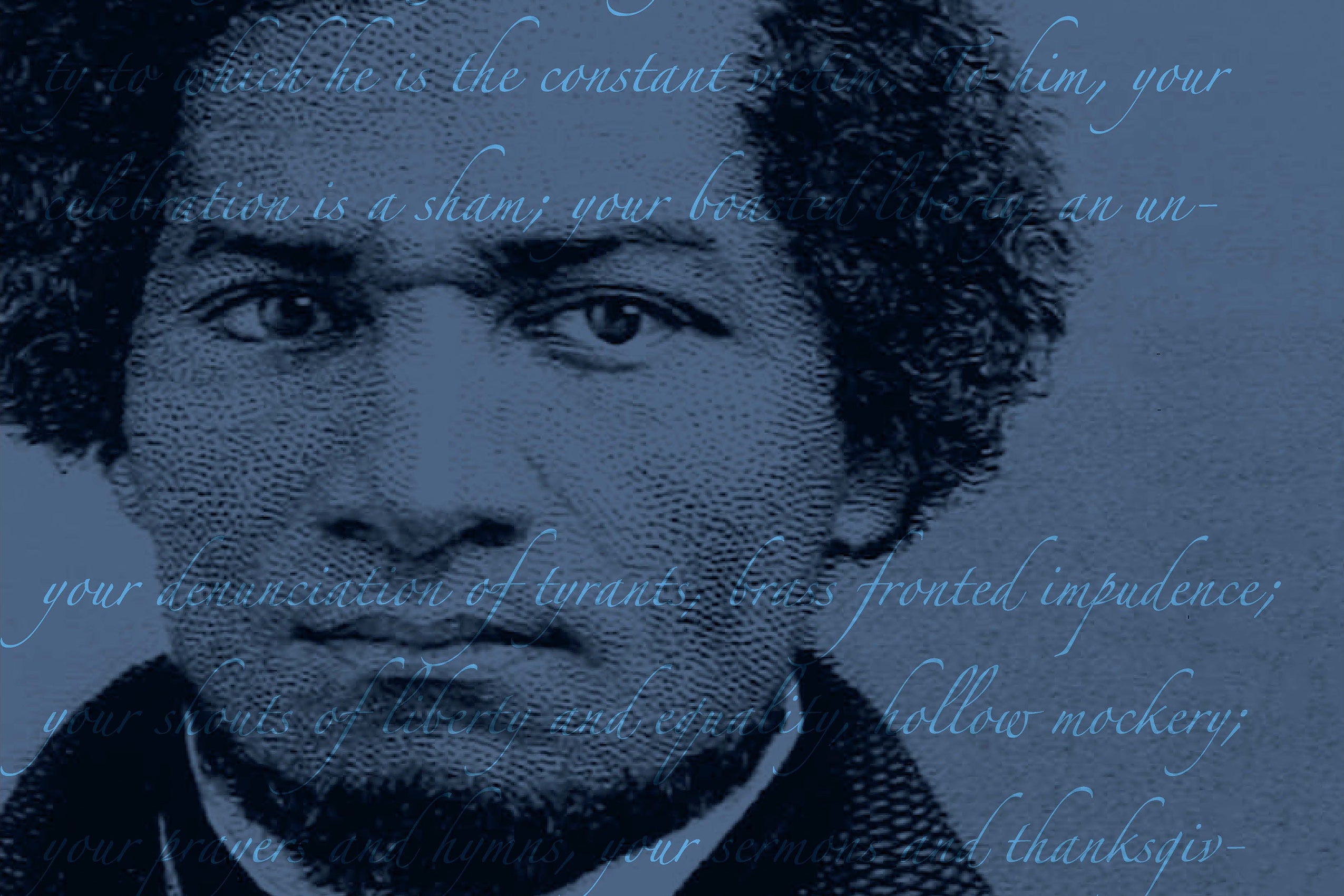

In an Independence Day address in 1852, abolitionist movement leader Frederick Douglass famously asked a gathering in Rochester, New York “What to the slave is the Fourth of July?” Answering his own question, it is a day, he said, “that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.” Douglass’ speech laid bare the hypocrisy of American ideals of freedom at a time when millions were living in Constitutionally-sanctioned bondage across the United States.

For more than a decade, people from across Massachusetts have gathered each year on Boston Common for a public reading of Douglass’s historic address. To safeguard participant’s health amid the coronavirus pandemic, this year’s event will be conducted live via Zoom on Thursday, July 2.

Last July, Harvard Law Today interviewed David Harris, managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice, the event’s cosponsor, about the annual public reading and the continued relevance of Douglass’ words. In the intervening year, events have demonstrated, according to the Institute’s website, that the “4th of July needs Frederick Douglass now more than ever.”

Harvard Law Today: Can you tell me a little bit about Douglass’ speech? What did he say and in what context?

David Harris: Douglass was known for his oratory and this speech is no exception. It is actually quite long—we use an abridged version for our readings—but despite its length it is at once riveting and concise. As with any great oration, Douglass builds to his point, which is to distinguish between the spirit of celebration typically surrounding the holiday and the misery suffered by enslaved people on that day and every day. He begins by praising the young nation and its origins in righteous protest against oppression by a tyrannical monarch. “It is,” he declares, “the birthday of your National Independence, and of your political freedom.”

In doing so he sets the stage to distinguish the holiday for his audience and establishes the gulf between those in his audience and those who remain in bondage. “My subject, then fellow citizens,” says Douglass, “is American slavery.” He brings that subject to life in vivid and sometimes horrifying terms, “Standing,” as he says, “with God and the crushed and bleeding slave on this occasion.” The effect is undeniable and its implications inescapable: the contradiction between the celebration and the bondage it masks demands action.

HLT: Douglass made the speech nearly a decade before the American Civil War, a conflict that ultimately led to the adoption of the 13th amendment, which ended slavery. Why is this speech still relevant today?

Harris: Well, we have all come to understand that while on its face this amendment appeared to outlaw forever slavery and involuntary servitude, its exception for those serving “a punishment for crime” left open the door for what Douglas Blackmon has called Slavery by Another Name and Ana DuVernay’s so painfully rendered film, “13th,” revealed as continued oppression in the 21st century. Douglass’s searing ability to cut through the rhetoric of freedom and democracy lives on in works like these that reveal the enduring cruelty of the exemption as it continues to haunt our flawed legal and punishment systems.

Indeed, in one of the most timeless passages in the speech, Douglass insists that the “character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this 4th of July,” adding as if speaking today, “Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.”

So, all these years later, our massive system of incarceration echoes Douglass’s charge that, “There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.” This is not to say there are not tyrannical regimes elsewhere in the world or that other nations do not abuse human rights, but it is the self-righteousness of our celebration in the midst of ongoing injustice that continues to resonate today.

We may finally be thinking about creating a commission to study the possibility of reparations—as with “all deliberate speed,” the American way of tackling a problem takes so much time and patience—and for this we can be thankful. We would be well advised to ponder Douglass’s speech as we frame this conversation. Indeed, his speech, which warns that “Your republican politics, not less than your republican religion, are flagrantly inconsistent,” should be required reading for any such commission.

HLT: Has the public reading of the speech each year on Boston Common—or the experience or meaning of it—changed over the years?

Harris: As I mentioned earlier, the first reading was designed to think about race in the “Age of Obama.” I remember that first year, looking out at the crowd I was filled with the kind of hope Douglass expressed at the end of his speech. I recall seeing a group of young blonde-haired children standing at the wall overlooking the reading as a group of late adolescents and young men sat on the adjacent steps on a lunch break from their work with YouthBuild. Neither group had any idea what would be going on when they happened by and I was truly heartened that both groups seemed to be intrigued and listening closely. It gave me such a surge of hope that the event could bring together such divergent groups. And that is one of the truly special elements, the combination of a core group of readers and the accidental attendees who happen by and hear bits and pieces of this incredible speech.

It seems that every year we have marked some anniversary with the reading, whether civil rights movement or Civil War related. This year we mark both the 400th anniversary of the arrival of captive Africans to the British colonies and the 65th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education. I have been thinking a lot about these two and have discovered that it is also the 400th anniversary of the first instance of representative government in Jamestown. That assembly, which represented property-owning men, took place on July 30, 1619. We have a precise date for that first, momentous vote, which set the pattern of exclusion with which we still live, but no such precision marks the arrival of 50 captive Africans sometime in August, 1619.

Understanding contradictions such as this is critical for honest conversation. For example, acknowledging all of the darker sides of our history makes it easier to understand why and how Colin Kaepernick taking a knee during the national anthem is actually an expression of the same kind of patriotism Douglass demonstrates in his critique of the United States. Both critiques seek true fidelity to those principles we fail to keep. Obviously, the speech has taken a much darker meaning in the Age of [President Donald] Trump. We feel the pain and anguish ever more severely and it is much harder to find hope for the future. But for me, the hope is in the very fact of gathering, of reading the speech in community, renewing the bonds with others who share a determination to change, and committing to act accordingly.

HLT: Do you think Douglass would be surprised to learn that Americans are reciting his words nearly 170 years later?

Harris: That’s a tough one for me. I generally try to avoid speculating about current or historical figures I don’t know. I don’t know what kind of person he was or how he thought of himself. Based on what I know of his writings, however, I think he would have very mixed feelings about the progress we have made. I think he would look at the ongoing gulf between our ideals and reality and might refer back to some of his own analysis to understand the current contradictions. This is a particularly difficult time for any such return, given the lack of civility and acceptance of intolerance that characterize our public discourse starting with the president.

HLT: Although primarily remembered for pointing out the hypocrisy of Independence Day in a nation that condoned the enslavement of millions of people, the speech also includes an interesting passage on the impact of globalization. Do you think that section has any lessons for us today?

Harris: Funny you should ask. Somehow I often find myself reading this paragraph and I’m always struck by its prescience. Noting the rapid changes in transportation and communication he insists that “Space is comparatively annihilated. Thoughts expressed on one side of the Atlantic are, distinctly heard on the other.”

What an understanding of the future this shows, although we know it is not all for the better. That annihilation of space has allowed for “real time” reporting of events, which in turn has led to considerable change around the world. He follows this observation by closing with words from William Lloyd Garrison, suggesting the new reach of the great abolitionist across the ocean as part of a global abolition movement.

I doubt even Douglass could have anticipated the technology we have or its uses. Our ability to communicate has led to much greater organizing and mobilization. Although it has also facilitated the spread of hateful ideas and untruths, I suspect Douglass, who understood perhaps better than anyone in the 19th century the power of images, would have reveled in our ability to capture and convey video of events. This power fuels modern abolition movements, whether of human trafficking, prison or police.

HLT: Can you tell me about the origins of the Reading Frederick Douglas Together project?

Harris: This project began in the library of an organization called Community Change, which was founded by Horace Seldon in 1968 to address the “white problem” at the root of American inequality revealed by the Kerner Report. The report is remembered for its conclusion that: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

In the early 2000s Community Change started a tradition of reading the Douglass speech in its library. A small group would gather in a circle and take turns reading paragraphs from the speech. I attended in 2008 and was deeply moved by the experience.

It occurred to me that it would be of interest to many others if they knew about it. Paul Marcus, then the director of Community Change, and I contacted another colleague, David Tebaldi, then executive director of the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities (now MassHumanities) about sponsoring a public reading. We convened a group of interested parties, met a few times over a couple of months, and decided to launch an event on the Common.

My original thought was a public reading prior to the holiday, which would prompt people to incorporate the speech or a discussion of its meaning in their holiday observations, whether in the back yard or the local library. That first year, 2009, was also President Obama’s first year in office. We were all giddy with the reality of a black president who had been willing to talk about race during the campaign. I said then and throughout his presidency that rather than freeing us from talking about race, his election freed us to talk about it; and we entitled that first event: “Reading Frederick Douglass in the Age of Obama.”

To safeguard participant’s health amid the coronavirus pandemic, this year’s Reading Frederick Douglass Together event will be conducted as a live virtual event via Zoom on Thursday, July 2.

The event is co-convened by the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice at Harvard Law School, Community Change, Inc., the Museum of African American History (Boston and Nantucket), and MassHumanities.

For more information on this event visit CharlesHamiltonHouston.org.

For more information on other communal readings scheduled throughout the state, visit MassHumanities.org.