Post Date: September 23, 2005

The following op-ed by Professor Philip Heymann and Juliette Kayyem, Limiting secrecy under the Patriot Act, originally appeared in The Boston Globe on September 22, 2005.

In the next week or so, Congress is expected to vote on a bill to renew certain expiring sections of the Patriot Act. The debate over this law is a crucial conversation for our country and for how we protect both the security and privacy of a free citizenry.

We are cochairs of the Long-Term Legal Strategy Project for Preserving Security and Democratic Freedoms in the War on Terrorism. We brought together a wide array of military, intelligence, and law enforcement experts, including some of the best minds from both sides of the aisle in the counterterrorism field, from the United States and Britain. Our report, for which only the two of us are finally responsible, offers recommendations on how best to protect civil liberties while confronting terrorists.

We studied the toughest questions in the post-9/11 era, including the conflicting demands of privacy and security. Particularly relevant for the debate over the Patriot Act are our findings on compelled government access to private, confidential records in terrorism investigations.

The Patriot Act gave expanded powers to the federal government to seize personal records (like those retained by hotels, libraries, and medical facilities) in special national security cases where court review is either diminished or nonexistent. The act allows the government to engage in a fishing expedition, demanding records without tying the request to a specific suspect or group (in other words, without ”individualized suspicion”) so long as its stated purpose is to find out something about a terrorist threat. For example, Section 215, which applies to a wide array of personal records, merely requires that the records themselves be sought for an investigation whose purpose is, in some way, ”to protect against” terrorism or spying by a foreign power — not necessarily an investigation focused on a specific event, person, or organization.

When there is no specific event or organization that the government is investigating, relevance or motivation simply doesn’t work as any limit on gathering information. Investigations undertaken in order to somehow protect against international terrorism could, if nothing more specific is required, examine any of the lawful activities of any citizen, including citizens in no way suspected of any specific link to terrorism or crime, such as subscribers of particular magazines. This has potentially serious implications for privacy and freedom of speech. Our project recommended that the standards for obtaining private, personally identifiable information in such investigations — for example, to obtain access to library records — should be based on individualized reasonable suspicion.

We believe that compelled access to personal records should depend on whether there is a judicial finding of a link between the records and an individual or organization already reasonably suspected of being engaged in terrorism or a specific planned or executed act of terrorism — or of being in contact with such a suspect.

We also believe that when the government demands confidential records in national security investigations using national security letters, the attached gag on the recipient should not be permanent (as it is now) but should be limited to 60 days and should be ordered or renewed only upon a showing of specific need to a judge.

The current Senate version of the Patriot Act renewal legislation reflects our concerns about the standard for secret records orders. It would, for instance, require a showing of facts suggesting a link between the records sought under Section 215 and a particular person or group or person in contact with a group.

Put simply, the government would have to put its cards on the table before the court (albeit in secret) rather than just asserting that the investigators believe some connection to terrorism exists, before using these highly secretive powers to demand the private records of Americans.

Unfortunately, both the House and Senate bills retain the permanent gag provision. The government’s certification that national security requires such secrecy is ”conclusive.” The House bill adds penalties, up to five years in prison, for violation of the gag. The First Amendment imposes an exacting standard for prior restraint of speech that cannot be squared with these provisions, and Congress should revisit them as soon as possible.

Although often obscured by the overheated rhetoric on both sides, the technical debate over how best to structure our laws to prevent terrorism while respecting our constitutional democracy poses the most important unanswered questions today. Unchecked compelled access by the government to our private information is only a part, but an important part, of this debate. Accordingly, we urge Congress to protect the reforms in the Senate Patriot Act bill.

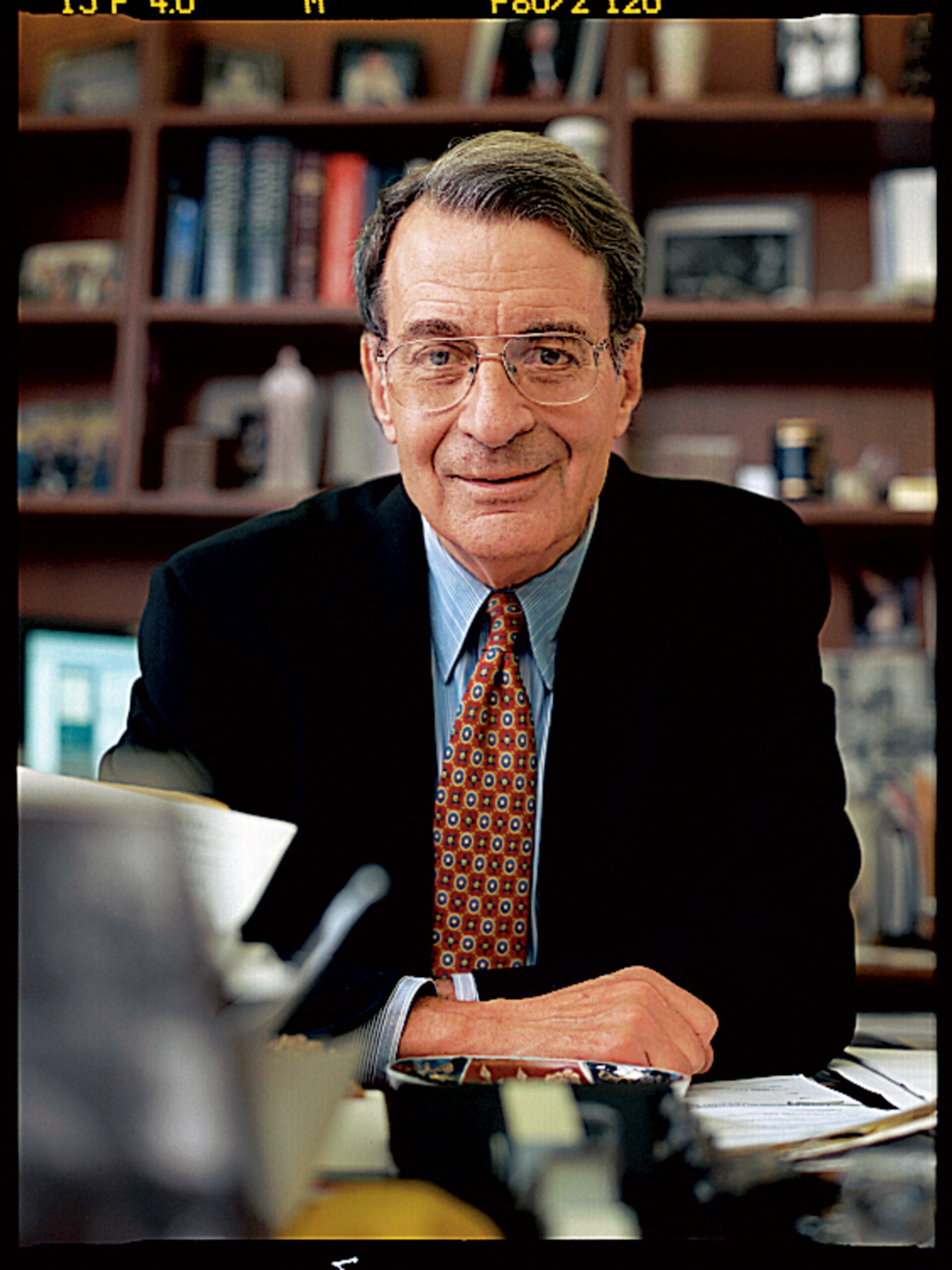

Philip B. Heymann is the James Barr Ames Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. Juliette N. Kayyem is a lecturer in public policy at Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.