Imagine if everyone did whatever they wanted, whenever they wanted, ignoring any laws and societal obligations to others. The chaos that reigns in the novel “Lord of the Flies” comes to mind. On the other hand, a society of only rules and punishments — and no individual freedom — might be oppressive and cruel.

While these two concepts — freedom and accountability — may seem mutually exclusive, nothing could be further from the truth, says Betsy A. Miller ’99, a lecturer on law at Harvard.

“These are polarities, which are interdependent opposites whose benefits together create the optimal conditions for success,” she says. “Polarities are not either/or choices like, ‘Should I vote for Trump or Harris.’ Instead, polarities appear in situations where choosing one or the other won’t bring you success — for example, ‘How do I have a conversation that is both candid and diplomatic? How can we respect the stability that legal precedent affords and change the law so that it evolves as needed?’”

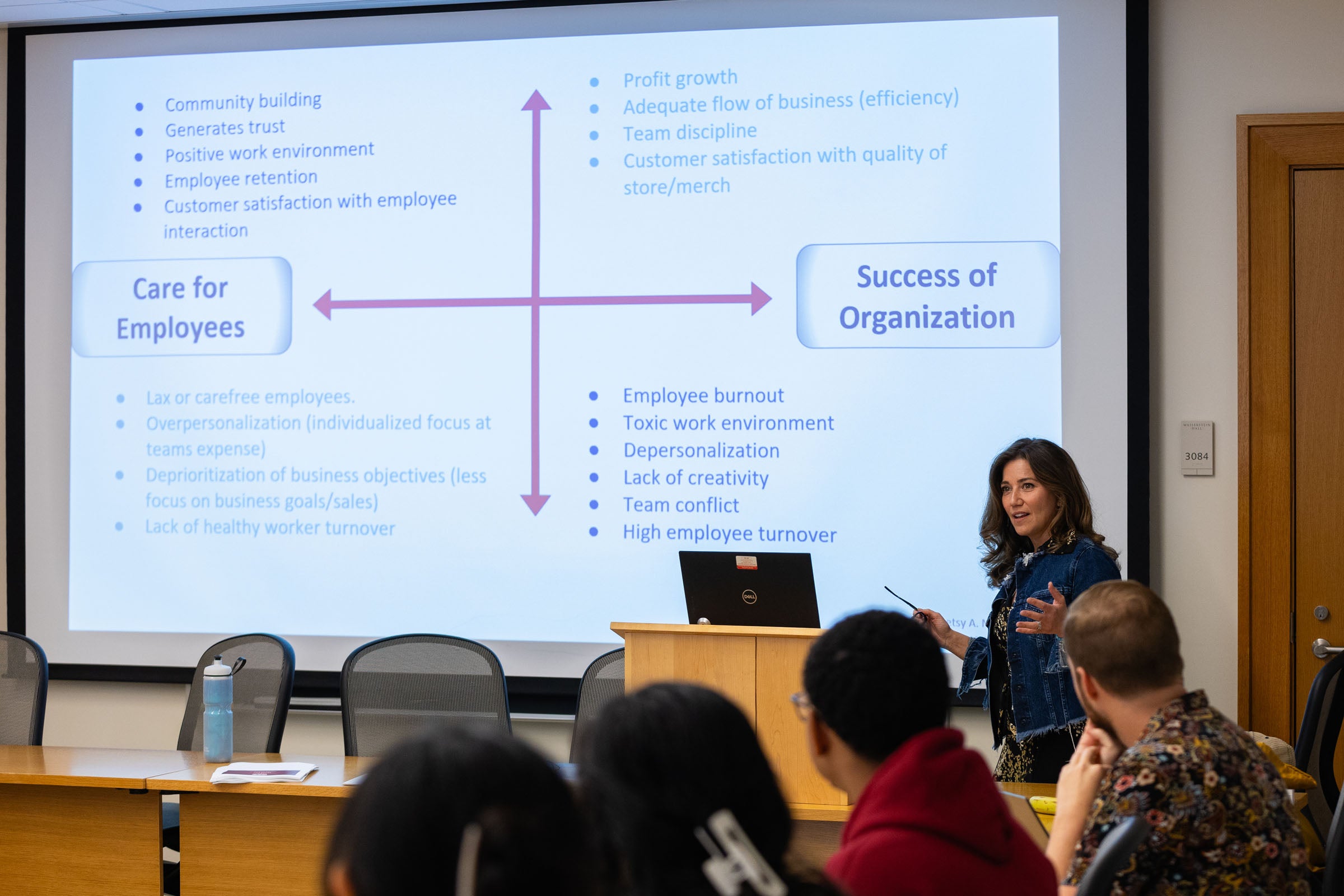

Miller’s Harvard Law School course, Polarities: Harnessing the Power of Opposites to Lead and Negotiate in a Complex World, is about recognizing — and negotiating — these types of tensions, in which neither option is sufficient on its own, but the benefits of both together hold the key to success.

Miller says polarities appear in all aspects of our lives, including our careers, in leadership roles, and even in our personal relationships. Should you take care of yourself or prioritize the needs of others? As a leader, do you provide your team with structure or flexibility? How can we make time to reflect while also acting decisively?

“Our instinct is to make decisions quickly, to choose one or the other,” Miller says. “Either/or decision-making is essential to survival, but we must recognize that certain situations cannot be navigated by making choices. Being able to see and leverage dynamics that require the ‘both/and’ thinking are critical leadership, negotiation, and life skills, because they help you understand and incorporate competing values.”

It is now more important than ever to learn how to navigate these types of tensions, Miller believes. “The world in which we live is tumultuous and increasingly polarized, and so, there is no better time to mainstream this content and teach young professionals and seasoned leaders how to think about different perspectives, conflicts, and contrasting value systems through a lens that many haven’t heard of before.”

But Miller cautions that not all opposites are polarities. “Tall and short are opposites, but they aren’t a polarity,” she says. “You don’t need the benefits of both being tall and short over time to succeed.”

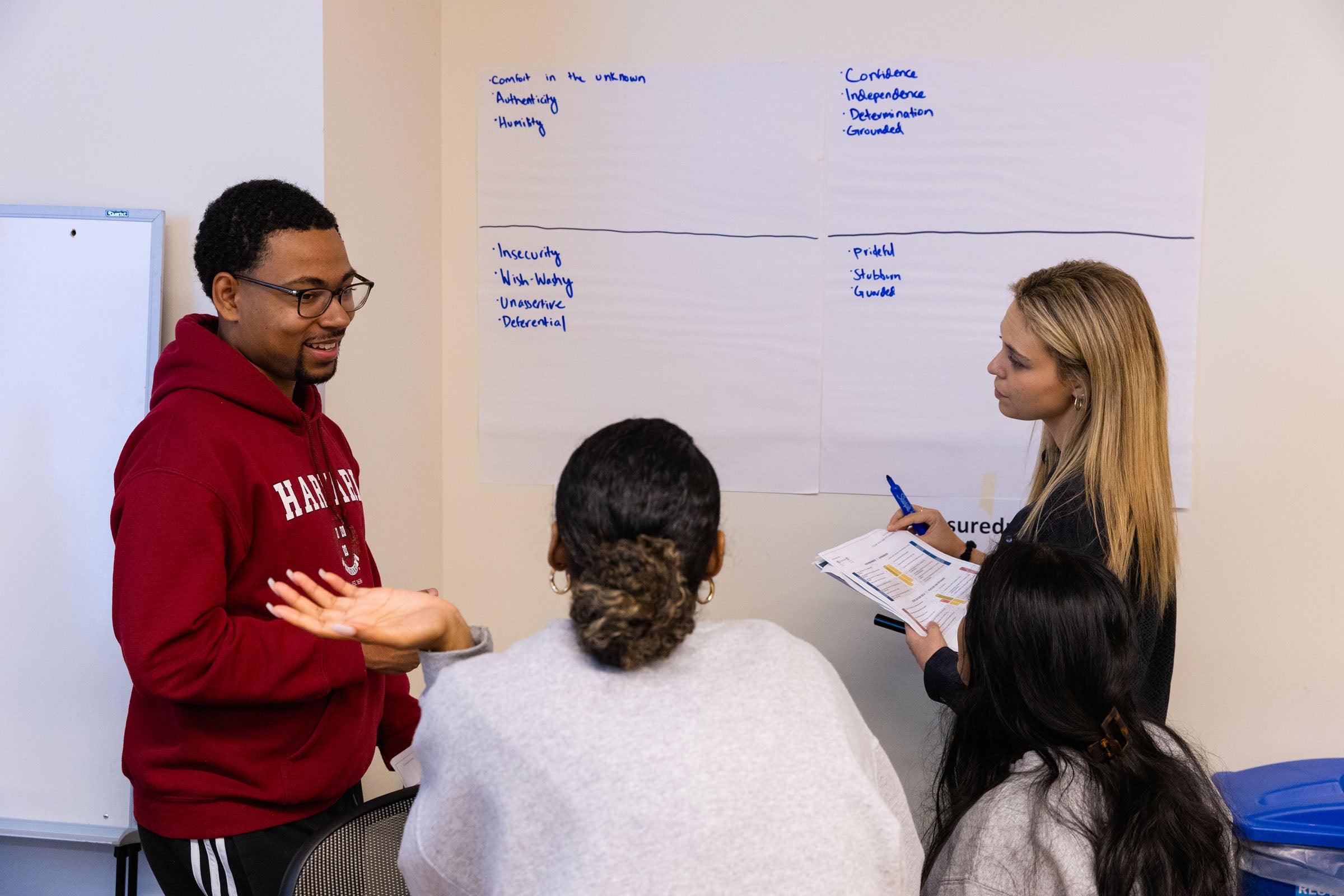

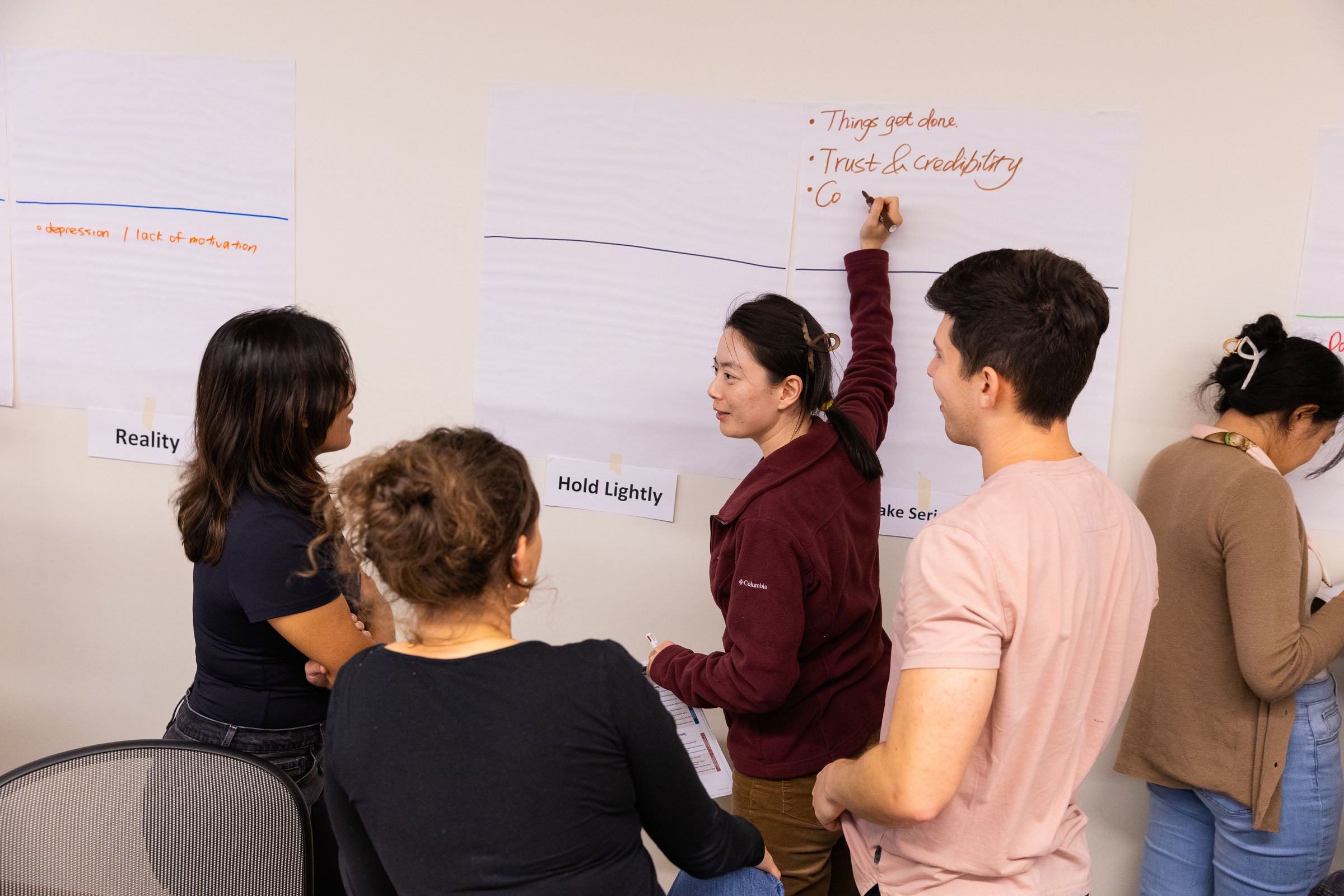

Miller’s course is highly interactive, with each class featuring a focused lecture followed by small group discussions, during which students collaborate to “map” a set of polarities, analyzing the benefits and overuses associated with each of the opposite poles, and then brainstorming ways to reap the benefits of both poles to arrive at an integrated “third way.”

Students also roleplay case studies in which they must apply this approach to real-world scenarios, such as those faced by companies like Apple or Disney. And Miller often brings in renowned guest speakers from various disciplines and careers to help students understand how they will encounter these types of choices in real life. This semester’s course included visits from a White House chief of staff, the dean of Dartmouth College, and a chief of police who used polarities to heal rifts in a community caused by gun violence. Students also write weekly reflection papers in which they identify challenges in their own lives and apply a polarities lens to unearth the interdependent opposites at play.

The goal, Miller says, is for future professionals to recognize that sometimes, the best choice is to not choose at all.

‘We can, and must, do both’

In addition to teaching classes on leadership and negotiation, Miller has long worked in and around politics, including as nominations counsel for the Senate Judiciary Committee, chief of staff and senior counsel for the attorney general of the District of Columbia, and as a practice group chair at a law firm where she represented state attorneys general.

Polarities often shape the political realm from the top down, but Miller says she developed her course out of a desire to do more work from the ground up, including mentoring students at the beginning of their legal careers.

“I was interested in catching early professionals when they are in a place of real curiosity about what mindsets are the best predictors of success and fulfillment and how they can create impact and maintain their sense of commitment and passion to their vocation,” she says. “This course sits at the intersection of vertical learning (which stretches your capacity) and horizontal learning (which provides tools and techniques). That combination is a powerful platform. Vertical and horizontal development are also polarities — opposites where you need both to grow and succeed.”

Polarities can be found throughout the law, Miller says, from questions about the goals and methods of the criminal justice system to debates over the friction between collective needs and individual rights. Should the law favor justice or mercy? Should the law prioritize individual freedoms or the collective good?

“In each of these situations, we can, and must, do both,” she says.

Even the legal profession itself is replete with polarities, Miller says. One example is how legal practices are being increasingly pressured to offer a more sustainable work-life balance to associates while maintaining high standards of performance and output for clients.

“Studies show that late-Millennials and Gen Z want and expect the work that they do every day to have meaning and impact, which means having a certain sense of autonomy and control over their own lives and flexibility about how they function as professionals,” Miller says. “However, when those preferences are taken to the extreme, they can produce a blind spot for the importance of structure and accountability.”

Finding a way to nurture flexibility while fostering success is crucial to attracting and retaining a diverse, world-class workforce, Miller argues in her recent law review article, BOTH: The legal profession’s struggle to leverage stability and change.

“This will be my 26th year as a practicing lawyer and my 24th year teaching law students, and what I am seeing is a real chasm of understanding generationally, where neither side has a healthy enough curiosity about, or understanding of, the competing value systems of the other generation,” she says. “But in truth, these competing preferences reflect a collection of interdependent opposites, where neither is sufficient on its own and the overuses of either produce undesirable results. They’re polarities. We need to know how to change, innovate, and adapt while respecting the key benefits that continuity and stability provide. In fact, this is how all evolution works — by maintaining functional elements of our DNA while also making room to replace the DNA that no longer serves us.”

Building a more empathetic, cohesive society

Abby Elder ’25, who hopes to continue exploring her passions for and building expertise in negotiation and alternative dispute resolution after law school, says she was attracted to Miller’s course last year because it promised a foundation for understanding and reducing division and facilitating difficult dialogues. She wasn’t disappointed.

“Betsy is a powerhouse. She’s an incredible, incredible teacher and thinker, and a generous human who really brought the material to life,” says Elder, who is now a teaching assistant for the course. “I think, for a while, my friends were almost sick of me talking about polarities.”

Sometimes, we recognize polarities in our lives, but don’t know how to talk about them, let alone resolve them, says Elder, adding that the course prompted her to consider not just how someone else feels, but why.

“So often, people get stuck in either/or thinking,” she says. “We ‘other’ people who don’t think the same way as us. But polarities thinking helps us understand why we are different and have different inclinations.”

It was that same desire to learn new ways to talk about these tensions that drew Elizabeth Bliss-Burger, a second-year Harvard Divinity School student, to the course. Before graduate school, she worked as a reentry counselor at Riker’s Island, helping incarcerated men gain the skills they need to be successful after prison.

“I’ve long thought about and grappled with the poles of forgiveness and accountability,” says Bliss-Burger, who is also a research assistant for the class. “I was excited to find another framework to describe the things I’ve been seeing and feeling, particularly as I continue to work with incarcerated people, and with other institutional stakeholders like judges, corrections officials, and parole officers.”

This lens can even benefit one’s personal life, Elder says. As an example, pretend you’re going on a trip with a friend who enjoys spontaneity, while you prefer a scheduled itinerary, she says. You want to be sure you can see the things you came to see, while your friend wants to feel as if they’re on vacation, not checking off items on a to-do list.

“The key takeaway is that both of these things have really important and helpful benefits to them,” Elder says.

In this situation, the polarities framework might help you understand your companion’s perspective — and her, yours — and you could ultimately end up with a better trip and a stronger friendship, says Elder. “Instead of getting frustrated at your friend or ending up in an argument, you can instead think about how to maximize the benefits of structure and flexibility.”

Elder says she believes all students could benefit from Miller’s course, even — or maybe especially — those who are interested in careers other than negotiation. “It’s a different, and valuable, lens for addressing how to reduce conflict and ultimately build more cohesive societies, workplaces, or even personal lives.”

Similarly, Bliss-Burger says she has urged her Divinity classmates to enroll in the course and thinks that it could be a boon for students from other Harvard schools too. “As an educator, I think about how one of my jobs is to translate ideas,” she says. “You’re a bridge builder, you’re a translator. Polarities thinking is another tool that can help me translate what it is that carceral organizations, jails, prisons are lacking, and how it can benefit all parties if we can tap into the other pole — that of forgiveness and mercy.”

It has also influenced Bliss-Burger’s career plans, showing her that she can continue to be a service provider to incarcerated people while also playing a larger role in the policies that shape the carceral system. “Without this class, I might not have been able to see how I could stay loyal to myself while also leaning into this new interest, this new part of myself I did not expect before coming to grad school.”

Elder, the law student, credits the class with improving her communications skills, adding that she now feels more comfortable — and productive — when engaging in hard conversations. “The class really helped me figure out how to show up authentically, but in a way that’s going to help me be understood, and also understand others better,” she says. “I feel like it helped me grow as a person.”

For Miller, that willingness to learn, to expand one’s capacity for empathy, and to be open to new ideas and solutions, is exactly the point.

“In this fraught time, it seems increasingly difficult for people to stay curious about values, perspectives and priorities that are not their own. What the polarities framework offers is a way to disarm the triggers that thwart these important conversations,” Miller says. “If I could wave a magic wand for humankind, the thing I would gift everyone is a renewed commitment to curiosity, and the realization that there is always something more we can learn.”

What would such a world look like? “Instead of feeling like you are swinging on a pendulum between opposing points of view that can’t co-exist, you can access the benefits of both and discover a sustainable and dynamic equilibrium.” It opens a whole new world, and one we sorely need.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.