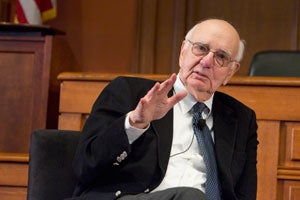

Paul Volcker, former chairman of the Federal Reserve under Presidents Carter and Reagan, and former chairman of President Obama’s Economic Recovery Advisory Board, was on campus in early April as a guest of the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics series on institutional corruption. The Center’s director, HLS Professor Lawrence Lessig, introduced him to an at-capacity crowd in Ames Courtroom before yielding the floor to Harvard Business School Professor Emeritus Malcolm Salter, who moderated a conversation with Volcker on the historical context of today’s financial crisis and current efforts to thwart future crises.

Depression-era regulations stabilized the American economy well into the 1960s, Volcker recounted. But economic confidence begat risk-taking, and the regulatory system was allowed to unravel. Instabilities emerged in the 1970s—but they were of a different kind than we see now, he said. For example, the Latin American Debt Crisis of the early 1980s, Volcker noted, was more manageable than today’s crisis because it involved banks. Deposits were insured by the FDIC, and banks could count on assistance from the Federal Reserve.

Today’s crisis, in contrast, was caused by enormous, non-bank financial institutions outside the control and protection of the Federal Reserve that were dealing in newfangled and ultimately rickety instruments, such as credit default swaps and mortgage-backed securities. It took extraordinary legal measures and billions of bailout dollars to address the collapse of one massive financial institution after another, Volcker said.

Financial institutions that survived 2008 sought federal protection by getting licenses to become banks. Banks, Volcker said, play a crucial role in society: They make loans, safely hold deposits, and run the world payment system. Because we rely on them, we give them special protection and special borrowing status. “If that’s all true,” Volcker said, “they ought to pay attention to their fundamental business and not get involved in all the activities that drove us over the cliff in the first decade of the century.”

Hence, regulation, and the Volcker Rule—a subset of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (2010). The Volker Rule, which is currently out for comments and scheduled for final promulgation this July, will, among other things, prohibit banks from trading on their own account. Volcker explained, “You [the banks] can trade for your customer and you may hold the security as part of your trading position, but you’ve really got to be dealing with customers. That’s the distinction we want. You shouldn’t be dealing and speculating on your own account.”

Volcker’s preference is to keep the written regulation simple, to state the general principle and administer the law from there. In his vision, the banks would manage their own control systems, keep statistical data, and report to regulators. Regulators would review the reports for patterns of proprietary trading and enforce the principle that way. Banks, however, prefer a different approach, he noted. They want a specific rule written to govern every possible transaction imaginable, which could make for an unwieldy regulatory scheme. But however the final rule looks in the end, what Volcker is after is this: to shift the ethical culture of the financial industry so that it is no longer in conflict with its customers.

As Professor Salter pointed out, the Volcker Rule has many insistent enemies. Regarding the heavily lobbied policymaking context to which reforms like the Volcker Rule are subject, Volcker said, “You want a response from the industry. What is not particularly helpful is that the response goes with a big campaign contribution to the senator or the congressman. … That is happening on a scale … that is just out of keeping with what was twenty years ago.”