Each May 1 the United States officially recognizes Law Day, a day intended for reflection on the role of law in the foundation of the country, and its continued importance for society.

The 2019 Law Day theme — “Free Speech, Free Press, Free Society” — focuses on these cornerstones of representative government and calls on people to understand and protect these rights to ensure, as the U.S. Constitution proposes, “the blessings of liberty for ourselves and our posterity.”

Notably, this year marks the centennial of Abrams v. United States, in which the concept of the marketplace of ideas first entered American jurisprudence in Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ famous dissent. Holmes argued that the First Amendment protects the right to dissent from the government’s viewpoints and objectives. Protections on speech, he continued, should not be curtailed unless there is a present danger of immediate evil, or the defendant intends to create such a danger.

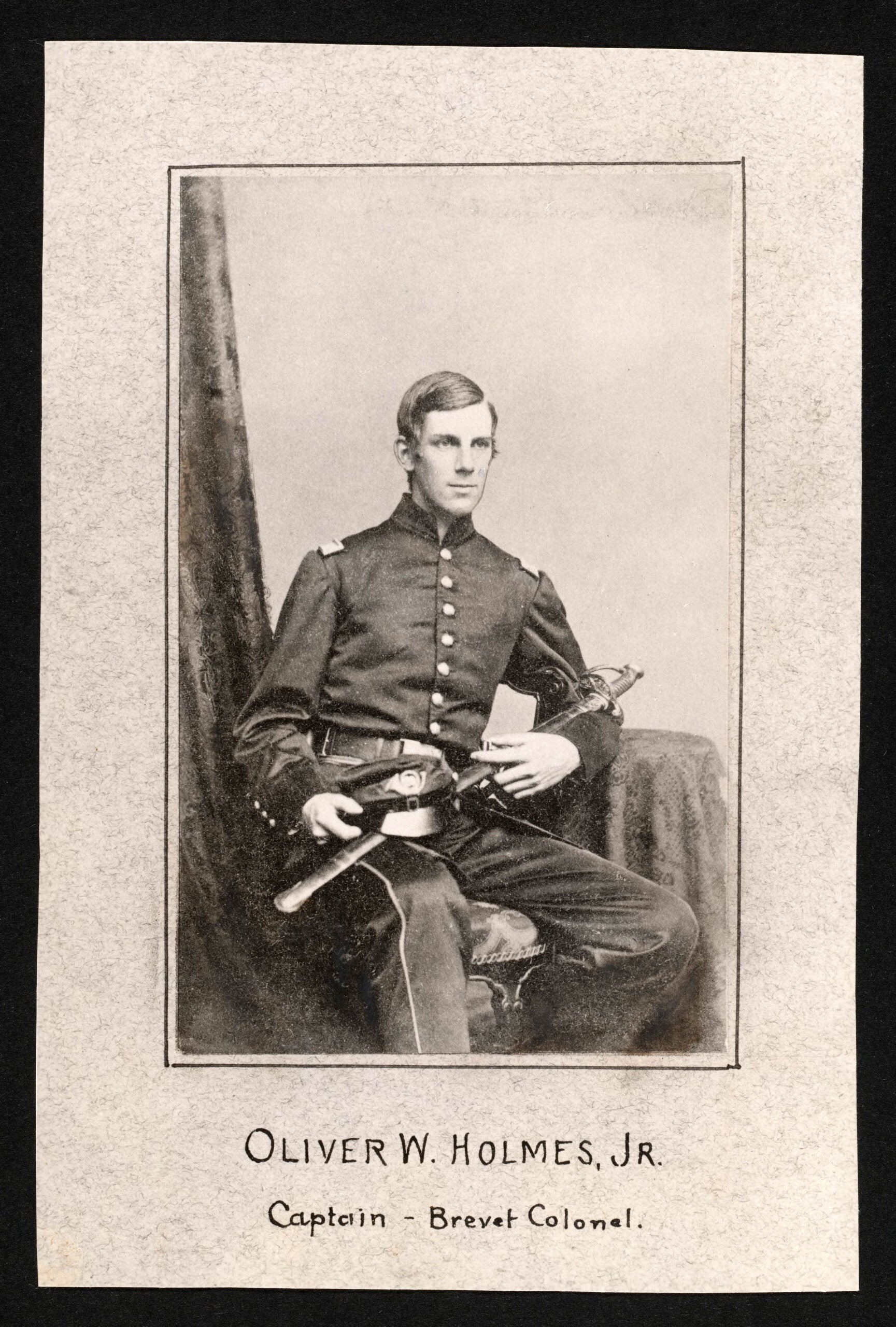

A new biography of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. by Stephen Budiansky, “Oliver Wendell Holmes: A Life in War, Law, and Ideas ,” illuminates the Supreme Court during the centennial of his most momentous dissent; a recent review of Budiansky’s book by Lincoln Caplan ’76 in the most recent issue of Harvard Magazine further explores Holmes’ contributions during his era, and his respect for the rule of law.

America’s Great Modern Justice

A new biography of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. illuminates the Supreme Court during the centennial of his most momentous dissent.

by Lincoln Caplan ’76

In the spring of 1864, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was fighting in the Civil War as a Union Army captain. He had enlisted three years earlier, soon after the war began, when he was 20 and in his last term at Harvard College, in the class of 1861. As an infantry officer in Virginia, he had received a near-fatal wound at Ball’s Bluff in his first battle, where he was shot through the chest in a Union raid that backfired. He had proved his valor by rejoining his men after he was shot, defying an order to have his wound tended. At Antietam a year later, where he was briefly left for dead on the bloodiest day in U.S. Army history, a bullet ripped through his neck. At Chancellorsville, in another eight months, an iron ball from cannon shot badly wounded him in the heel. Near there in winter, “Holmes lay in the hospital tent too weak even to stand as he suffered the agonies of bloody diarrhea,” Stephen Budiansky, M.S. ’79, writes in a new biography of Holmes: “The disease killed more men than enemy bullets over the course of the Civil War.”

That spring, generals Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee met on the battlefield for the first time. Grant, the newly appointed commander of the Union Army, had shifted its main target from Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, to Lee and his roving Army of Northern Virginia. The Battle of the Wilderness was the opening fight. In fierce encounters over two days, of 119,000 Union soldiers, one of seven died or was injured; one-sixth of Lee’s 65,000 troops were casualties. Holmes filled a new role as an officer on horseback in the Wilderness. As Budiansky recounts, he faced “the most intense and nightmarish episode of the entire war for him, nine weeks of nonstop moving, fighting, and killing that would often find him falling asleep in the saddle from sheer fatigue, escaping death by inches, and witnessing carnage on a close-up scale that eclipsed even his own previous experiences.”